Lugares onde o céu caiu em cima da Terra

Este tema está dividido em 4 partes:

Parte 1 – Parte 2 – Parte 3 – Parte 4

For English version click here

Lugares onde o céu caiu em cima da Terra – Parte 3

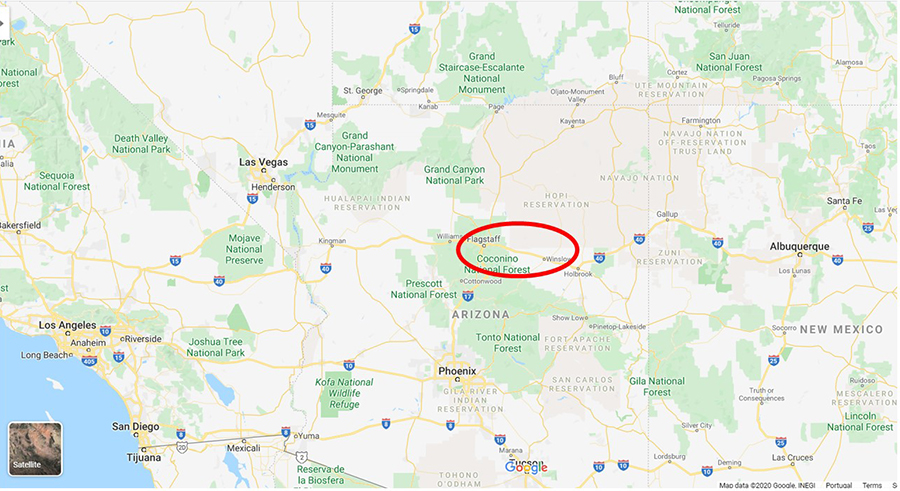

Setembro 2010. Finalmente, uma cratera “a sério”…! Esta toda a gente conhece, por um nome ou outro: Cratera do Meteoro, Cratera de Barringer, e por aí fora. Curiosamente, e ao contrário do que se poderia pensar, este fantástico terreno não pertence ao governo dos EUA. Trata-se de uma propriedade privada, da família Barringer. Que explora o sítio, claro, cobrando um bilhete a cada visitante, e decidindo até onde vai o acesso. Com alguma ajuda, pois então: há uns anos, ao que parece, uma turista seguia de chinelos pelo trilho que permite descer ao chão da cratera, sobre um terreno pedregoso, repleto de calhaus soltos… Duas coisas previsíveis aconteceram: a turista conheceu de perto o sabor do pó desta zona do Arizona; e os proprietários do terreno foram processados pela dita cuja. Resultado: não há descidas ao fundo da cratera para ninguém (excepto em casos muito especiais). Aliás, os visitantes normais estão agora limitados a apreciar a cratera dos pontos preparados para isso, e não podem circular em volta da cratera, excepto em visitas guiadas.

Mas o grupo em que me integrava não era um grupo de visitantes normal. A visita fazia parte do programa de uma reunião científica do Planetary Crater Consortium, que estava a decorrer na sede do Astrogeology Branch do USGS, em Flagstaff, a alguns quilómetros de distância (quer dizer, milhas… em Roma, sê romano, mesmo que não faça sentido). Era guiada por Nadine Barlow, uma especialista no estudo das crateras… de Marte, professora na Northern Arizona University (não confundir com a Arizona State University, de Phoenix, nem com a University of Arizona, de Tucson; o Arizona é uma paisagem feita para o estudo da geologia, e todas elas têm fortes programas na área, e ligações à exploração planetária). E, portanto, ali estávamos, prontos a enfrentar umas horas de caminhada sob o inclemente sol do Arizona, a dar a volta à cratera.

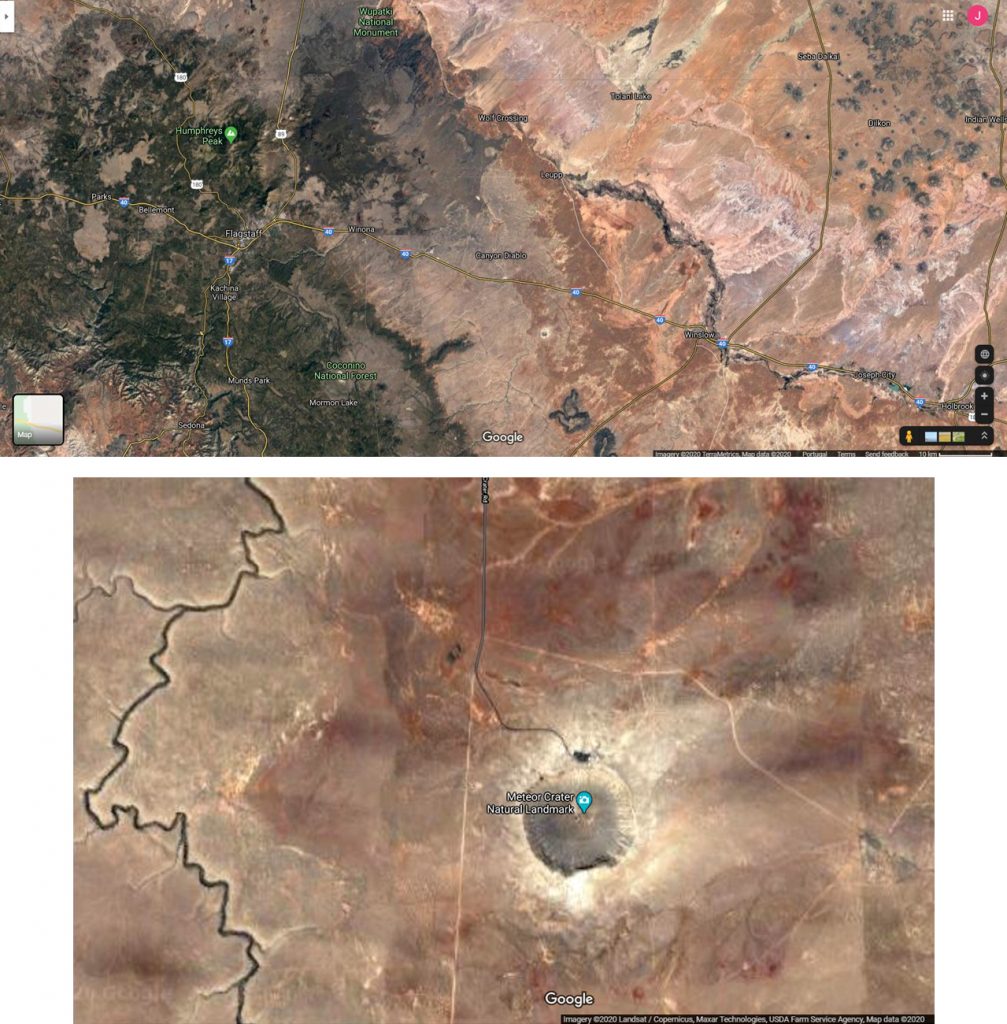

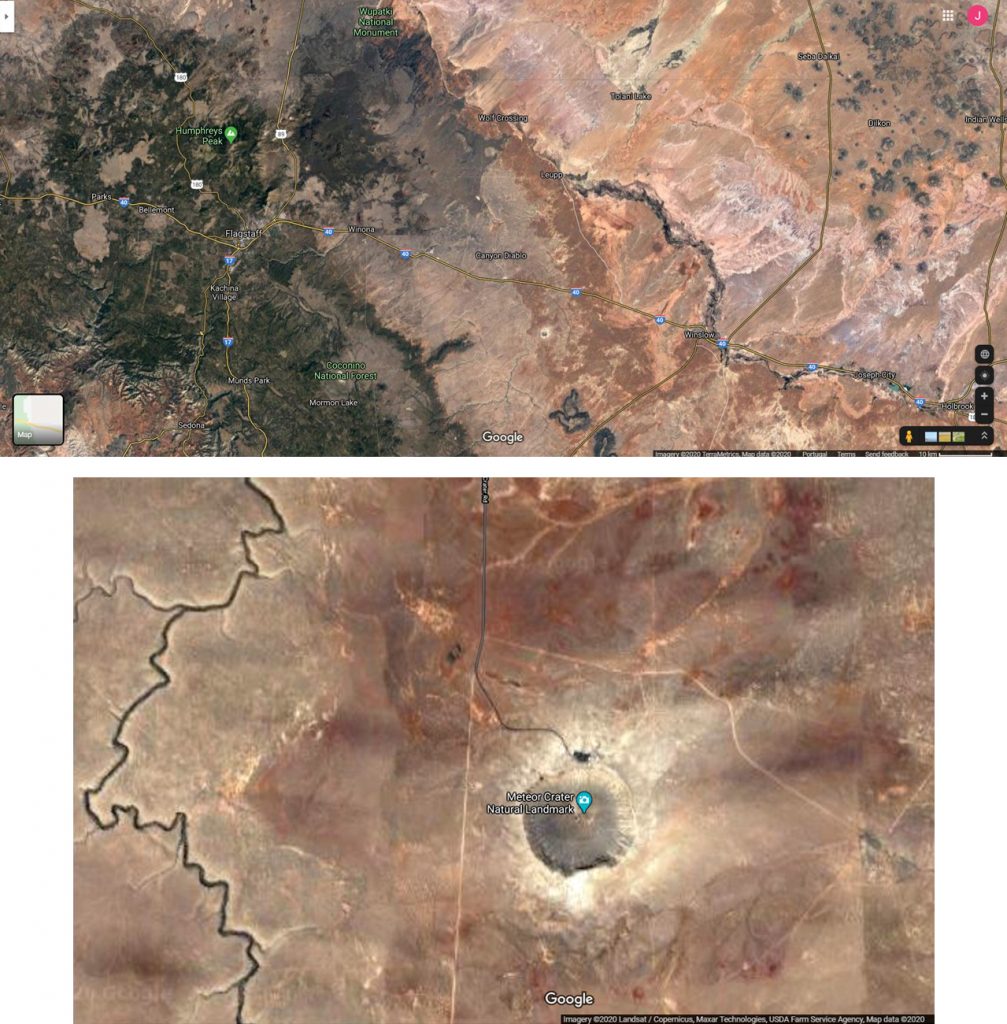

Uma volta algo estranha, de facto. Quem olhar com atenção para uma imagem da cratera vista de cima decerto repara que ela tem um ar… quadrado. Terá sido resultado de um objecto com essa forma? Não; o que se passa é que a estrutura geológica da área – as fracturas no terreno – levou a essa morfologia. A cratera tem cerca de 1,2 km de diâmetro, e portanto uma circunferência de um pouco menos de 4 km. De profundidade tem menos de 200 m, já que na depressão se acumularam sedimentos do tempo em que esteve ocupada por um lago. A cratera foi formada há cerca de 50000 anos, por um objecto metálico com cerca de 50 m de tamanho, que se terá em larga medida vaporizado – mas deixando muitos fragmentos em redor. O clima local ajudou à preservação da cratera numa forma semelhante à original.

E quanto à história do estudo da cratera? Bom, no fim do século XIX, havia já quem defendesse a ideia de que se tratava do resultado do impacto de um corpo celeste de composição metálica. Assim sendo, o lógico era que houvesse uma massa metálica de grande valor enterrada no centro da cratera – porque não explorá-la? E bem tentaram encontrá-la, ao longo de vários anos, mas nada feito; ao tempo, a dinâmica dos impactos meteoríticos estava muito longe de ser estudada, quanto mais compreendida. Resultado: o regresso da então habitual hipótese vulcânica. Foi preciso chegarmos à segunda metade do século XX e ao suspeito do costume: Eugene Shoemaker. Foi ele quem colheu as amostras em redor da cratera que, analisadas, revelaram a presença de coesite, mineral que indicava a tremenda pressão de um impacto meteorítico. Foi a primeira vez que se detectou coesite na natureza, e a descoberta foi anunciada num artigo na Science, em 1960. A tese de Shoemaker debruçou-se sobre a cratera, demonstrando cabalmente a sua natureza – foi também a primeira vez que esse facto foi aceite de forma indiscutível.

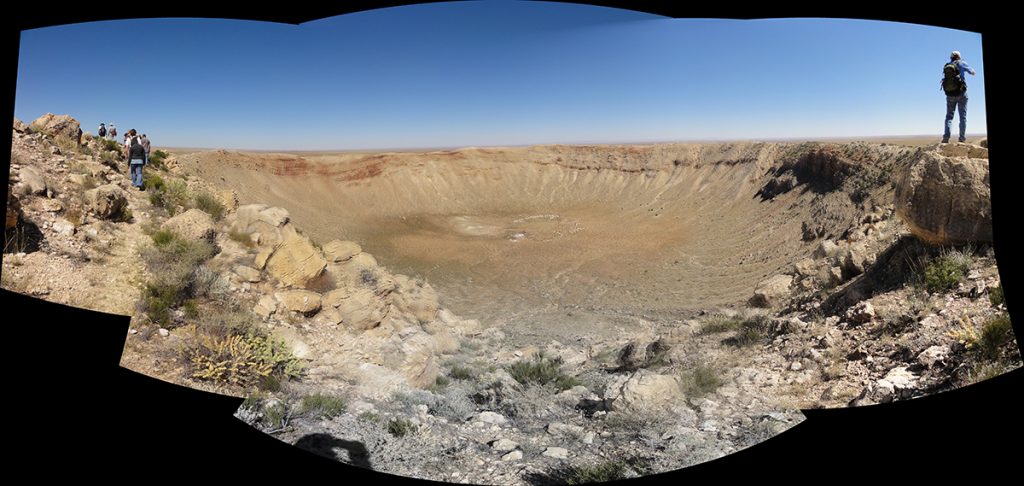

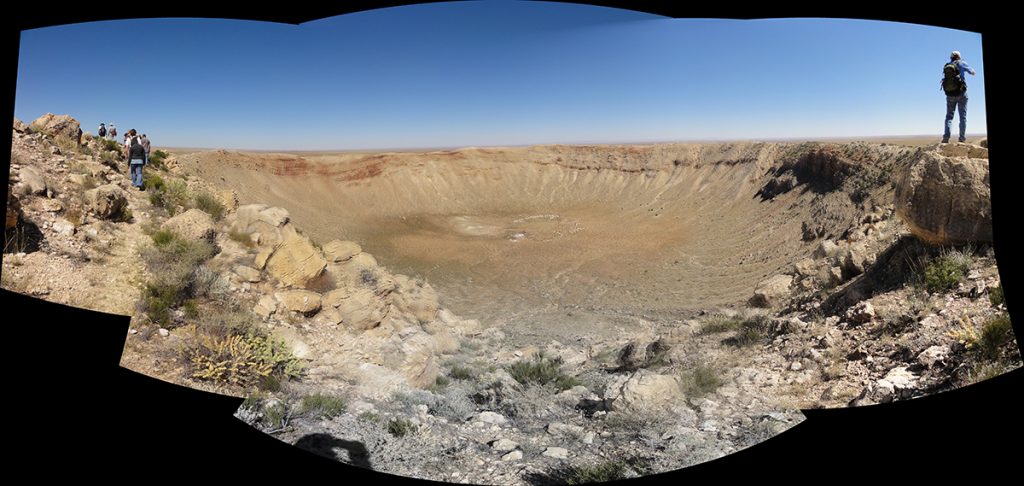

Quanto à volta à cratera, creio que as imagens serão mais esclarecedoras.

Finda a visita, uma rápida passagem pela loja de recordações, a t-shirt da ordem, e o regresso a Flagstaff com a alma cheia. Uma visita daquelas que ficam para sempre na memória.

E para quem quiser saber mais sobre esta cratera:

– O site da própria companhia que explora a cratera, com ênfase na história da investigação sobre a mesma:

– Como diz o nome, um guia recente e muito completo para a geologia da cratera:

Guidebook to the Geology of Barringer Meteorite Crater

Nota: o autor do texto não escreve segundo o novo Acordo Ortográfico.

ENGLISH VERSION

This theme has four parts

Part 1 – Part 2 – Part 3 – Part 4

Places where the heavens fell on Earth – Part 3

September 2010. Finally, a “real” crater…! Everyone can recognise this one, by a name or another: Meteor Crater, Barringer Crater, and so forth. Funnily enough, and contrary to popular belief, this amazing piece of real estate does not belong to the federal government of the USA. It’s a private property, and belongs to the Barringer family. And they explore it: they allow access for a fee, and determine where visitors can go. They had a little help, of course: some years ago, apparently, a tourist was climbing down the trail that leads to the floor of the crater in her comfortable flip-flops, over rocky ground, full of loose pebbles. Two very predictable things happened: the tourist had a close and personal meeting with the dust of Arizona; and the owners of the crater were sued by her. The result: no one is allowed to go down to the floor of the crater (except very special cases). The normal visitors are only allowed to appreciate the crater from the prepared lookout points, and can’t go around the crater, unless they’re part of a guided tour.

The group of which I was a part, however, didn’t fall under the category “normal visitors”. The tour was part of the program of a scientific meeting of the “Planetary Crater Consortium”, taking place at the headquarters of the Astrogeology Branch of the USGS, in Flagstaff, a few kilometres away (sorry, miles… when in Rome… even if it doesn’t make any sense). Our guide was Nadine Barlow, an expert on craters, especially on Mars, a professor at the Northern Arizona University (not to be confused with the Arizona State University, in Phoenix, nor with the University of Arizona, in Tucson; Arizona is a natural landscape for the study of geology, and all three universities have strong programs in the discipline, and connections to planetary exploration). And so there we were, facing a few hours of walking under the scorching Arizona sun, going around the crater.

Around, but not round. If you look closely at an aerial image of the crater, you will notice that it has a… squarish look. Could this be due to a square impactor? Not really – this has to do with the geological structure of the area – the fractures on the ground. The crater is 1.2 km in diameter, and so a little less than 4 km in circumference. It’s around 200 m deep, given that there is an accumulation of sediments in the bowl, due to the lake that was there for some time. The crater was formed 50000 years ago, by a metallic object of around 50 m in dimension, that was largely vaporized – but left many fragments in the surrounding area. The local dry climate helped in the preservation of the crater in a similar shape to the original.

What about the history of the studies done about the crater? Well, already at the end of the 19th century there were those who favoured the idea that it was a result of the crash of a celestial body with a metallic composition. Thus, logically, there should be a large and valuable mass of iron buried at the centre of the crater – why not exploit it? Huge efforts were done to try to find it, through many years, but to no avail; at the time, the dynamics of meteoritic impacts were far from a subject of study, let alone understanding. The result was the return of the usual volcanic explanation. Only in the second half of the 20th century did the usual suspect come into the scene: Eugene Shoemaker. He collected the samples from around the crater that revealed the presence of coesite, a mineral that indicates the huge pressures involved in a meteoritic crash. This was the first time that coesite was found occurring naturally, and the discovery was made public on a paper in Science, in 1960. Shomeaker’s PhD thesis was about the crater, and demonstrated beyond any doubt its true nature – and for the first time the existence of impact craters on Earth was fully accepted.

As for the crater tour, images will, I believe, be more explanatory.

With the tour finished, it was time to take a look around the shop, buy the “mandatory” t-shirt, and return to Flagstaff with a full soul. This was the type of visit that remains in the memory forever.

And if you want to find out more about Barringer crater:

– The site of the Barringer company that explores the crater, with a focus on the history of the research about it:

– As the name says, a recent and very complete guide to the geology of the crater:

Guidebook to the Geology of Barringer Meteorite Crater

Leave a Reply