Lugares onde o céu caiu em cima da Terra

Este tema está dividido em 4 partes:

Parte 1 – Parte 2 – Parte 3 – Parte 4

For English version click here

Lugares onde o céu caiu em cima da Terra – Parte 2

Setembro de 2019. O EPSC (European Planetary Science Congress) tinha-me levado até à Alemanha; mais concretamente, a Potsdam, nos arredores de Berlim, terra prussiana de lagos, palácios e jardins. Mas, depois de terminado o Congresso, foi altura de pegar na trouxa e atravessar boa parte da Alemanha de comboio, rumo ao sul. Objectivo: Nördlingen, uma pequena vila medieval, murada, a norte de Augsburgo, e que é famosa por dar parte do nome a uma cratera bem conhecida: o Ries (a outra metade, e mais usada, da designação).

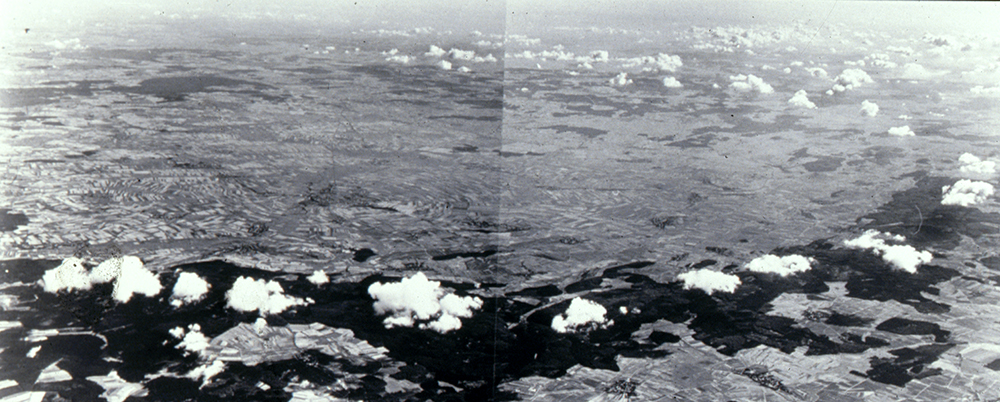

Se olharem para uma imagem do Google Earth, ela salta logo à vista… não é? Pois, não.

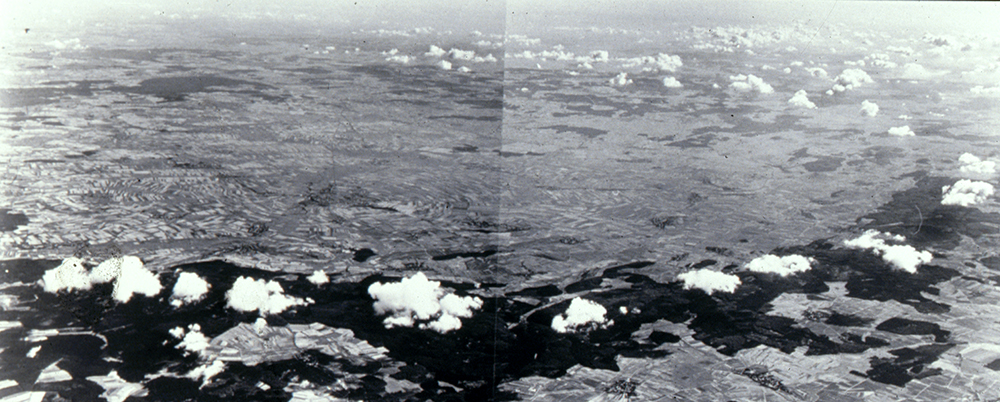

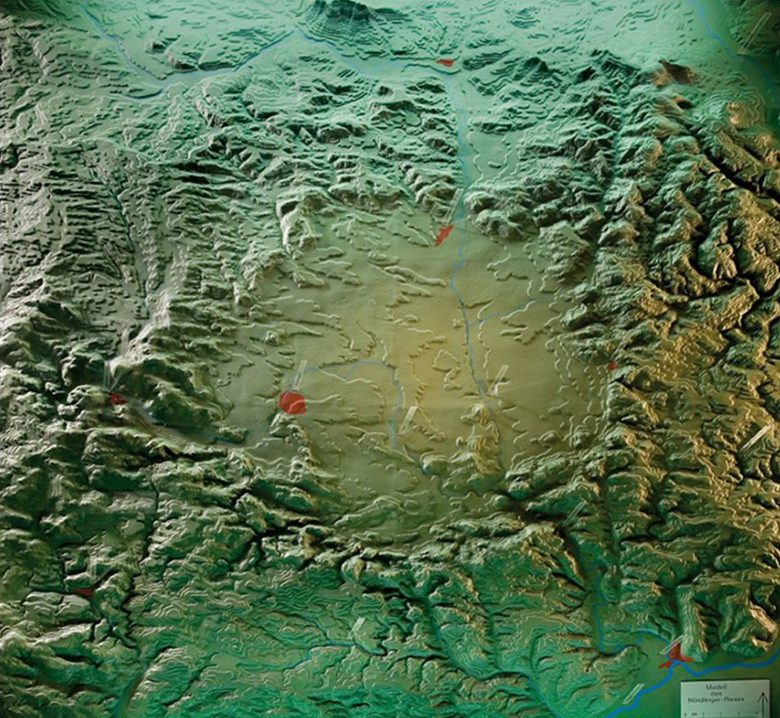

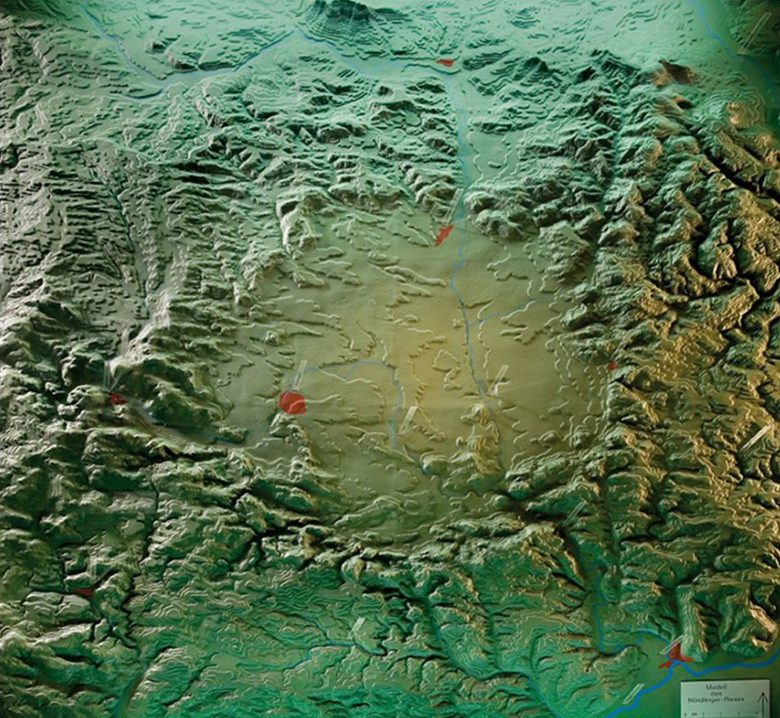

O museu local proclama que se trata da maior e mais bem conservada cratera de impacto da Europa. Bem, convenhamos que assim é. Mas, mais uma vez, pisando o terreno, não é fácil determinar que estamos em plena cratera. Porquê? É uma questão de dimensão – são 24 km de diâmetro. É também, outra vez, uma questão de idade – são quase 15 milhões de anos, e a Terra não descansa. E assim, a depressão que foi criada por um objecto cósmico com uma dimensão de cerca de 1,5 km, a uma velocidade de 20 km/s – um impacto que libertou uma energia equivalente a 1,8 milhões de bombas de Hiroshima – foi depois disfarçada pelos materiais que sedimentaram no lago que a ocupou. Portanto, para vermos a cratera no seu conjunto, a única solução será alugar um pequeno avião… ou olhar para uma fotografia clássica, tirada do ar. Por outro lado, olhando para um modelo da topografia da região, então sim, vemo-nos obrigados a reconhecer: a cratera salta à vista.

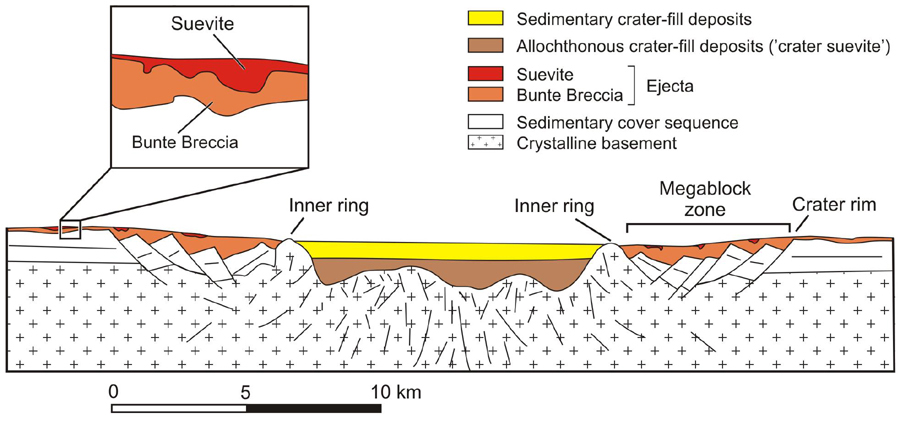

Nördlingen é rodeada por uma muralha circular – mas esse anel fortificado tem 1 km de diâmetro, o tamanho da povoação medieval. Ela não ocupa a cratera; na realidade, situa-se sobre a orla do anel interior – porque o Ries é uma cratera complexa.

Ainda assim, a vila teve um papel importante no reconhecimento da natureza da cratera. Como de costume, as explicações iniciais para a estrutura circular recorriam a fenómenos vulcânicos – só faltavam à chamada… as rochas vulcânicas. Mistério.

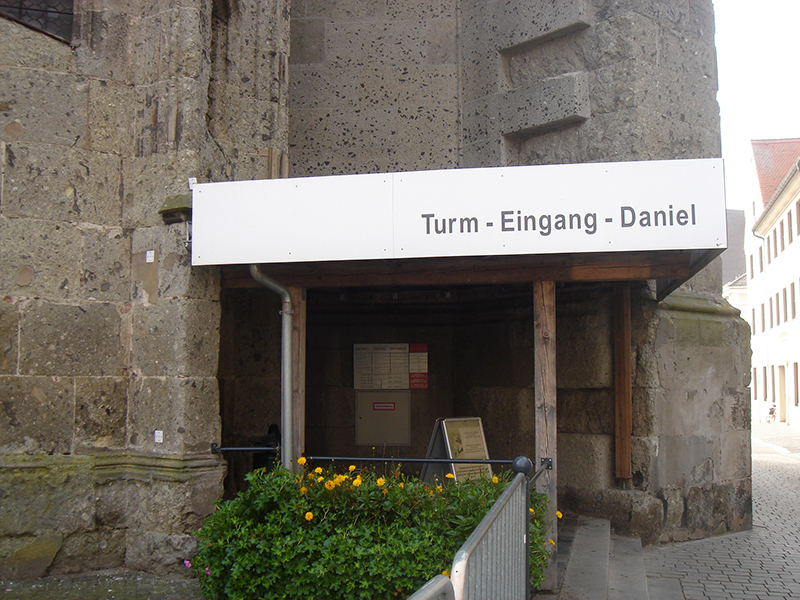

Então, em 1960, Eugene Shoemaker e E. T. Chao visitaram a região. Shoemaker foi um geólogo cujo sonho era ser astronauta e ir à Lua; infelizmente, um problema médico cortou-lhe o sonho. E em vez disso ele foi um dos criadores do ramo de Astrogeologia (Astrogeology Branch) dos Serviços Geológicos dos EUA (USGS), instrutor de Geologia de astronautas do programa Apollo, e também um homem que nunca se cansou de procurar crateras de impacto na Terra (faleceu na Austrália, numa visita a uma cratera remota). Entre visitas a pedreiras e outros locais onde era possível investigar a fundo a geologia local, Shoemaker apreciou os edifícios da localidade; entre eles, a alta (90 m) torre da igreja, que tem nome e tudo: Daniel. E nas pedras locais com que foi construída a torre, estavam as provas da sua origem por impacto – mais uma vez, o suevito, com os vítreos fragmentos rochosos que foram fundidos em resultado da escavação da cratera e arrefeceram rapidamente ao percorrer a atmosfera, pelo que não cristalizaram.

Para quem não tinha nem tempo (nem t€mpo) para grandes explorações pela região, e depois de subir à torre e ver à distância as elevações que marcam a orla exterior da cratera, a melhor maneira de a conhecer era mesmo uma visita demorada ao museu, situado na praça Eugene Shoemaker.

Infelizmente, não estava naquela altura prevista nenhuma visita aos pontos de interesse geológico da região (nessa altura, não conhecia ainda algumas das pessoas do museu, com quem partilharia a visita a outra cratera, pouco mais de um ano depois). O museu é interessante e detalhado. “Esqueceram-se” foi de colocar informações em inglês… O meu muito limitado conhecimento da língua de Goethe deixou-me, portanto, na posição de “ver os bonecos”.

Para lá da história da cratera (a geológica e a humana), e de amostras dos diversos tipos de rochas locais, havia meteoritos vários, e um pedaço de pedra lunar – perante a falta de precauções para a sua protecção, perguntei se não estavam preocupados com a possibilidade de um roubo… Recebi olhares horrorizados – como poderia alguém, na Alemanha profunda, pensar sequer em roubar uma pedra tão importante? Bom, não foi só a portuguesa (oferecida como gesto de boa-vontade pelos EUA, depois das missões Apollo) que desapareceu…

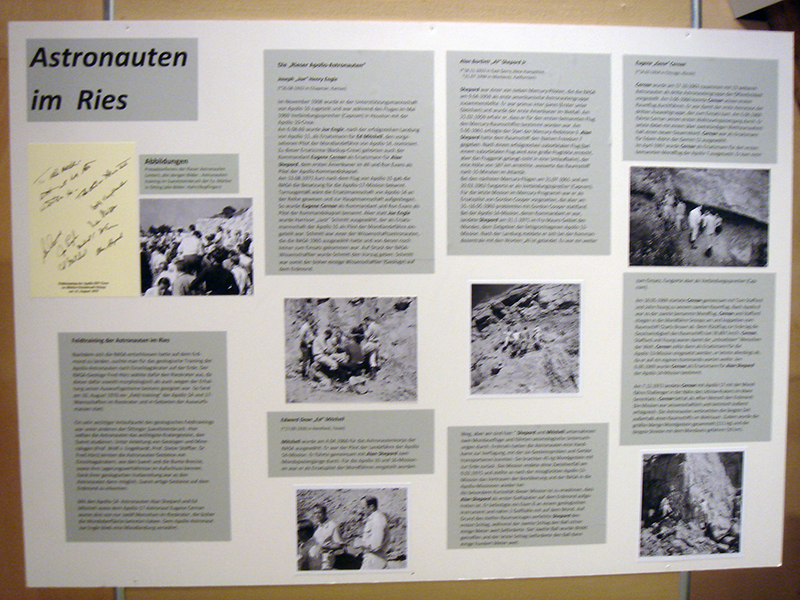

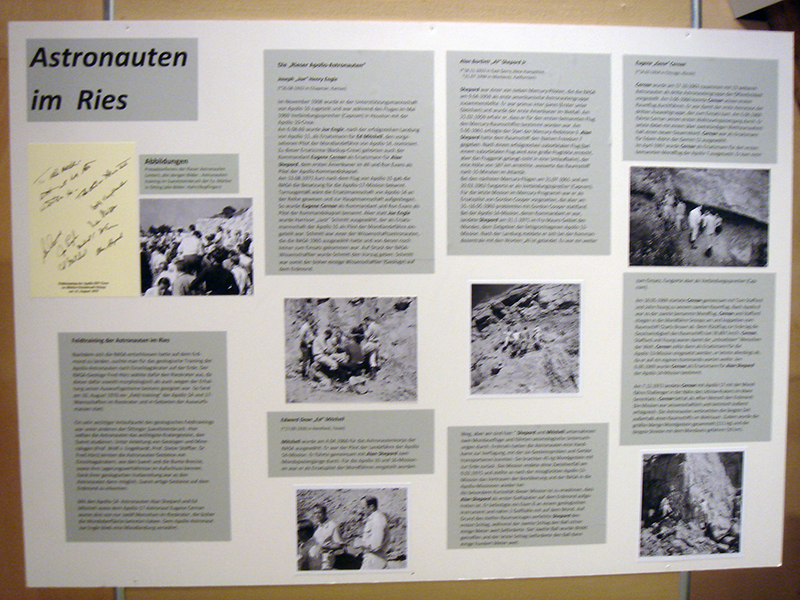

Por falar em astronautas, é dado relevo às visitas de vários astronautas à região. Não para actividades sociais, e sim para umas sessões de treino geológico (com Shoemaker e outros), em preparação para a exploração lunar.

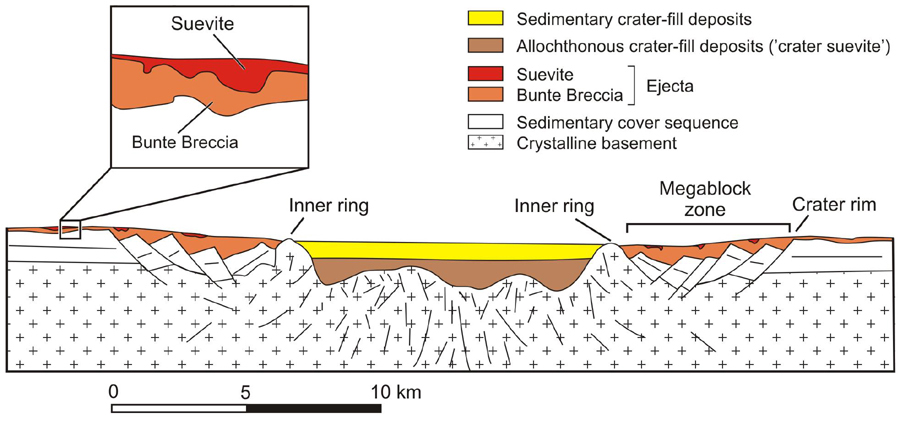

Olhando para os esquemas geológicos, percebe-se a complexidade da cratera. Na zona exterior, o impacto provocou uma série de fracturas com deslizamentos, sobre os quais se depositou um grande volume de material ejectado e brechificado. Assim, a verdadeira orla da cratera situa-se nessa área, que corresponde ao terreno elevado que se avista do cimo da torre Daniel.

Para concluir a história do Ries: a alguns quilómetros (cerca de 40) a sudoeste fica outra cratera, mais pequena, de nome Steinheimer, com a mesma idade. Há relação? Sim, julga-se que o objecto responsável se quebrou, e o fragmento mais pequeno, com uns 150 m de diâmetro, foi o responsável por essa cratera menor. Para além disso, o Ries foi responsável pela ejecção de gotículas de material fundido que viajaram até mais longe e criaram um campo de tectites na República Checa, conhecidas como moldavites.

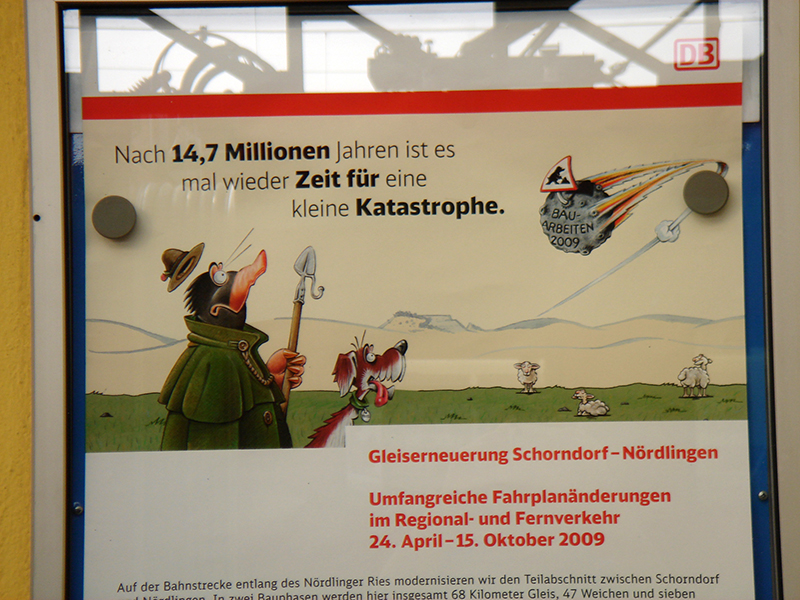

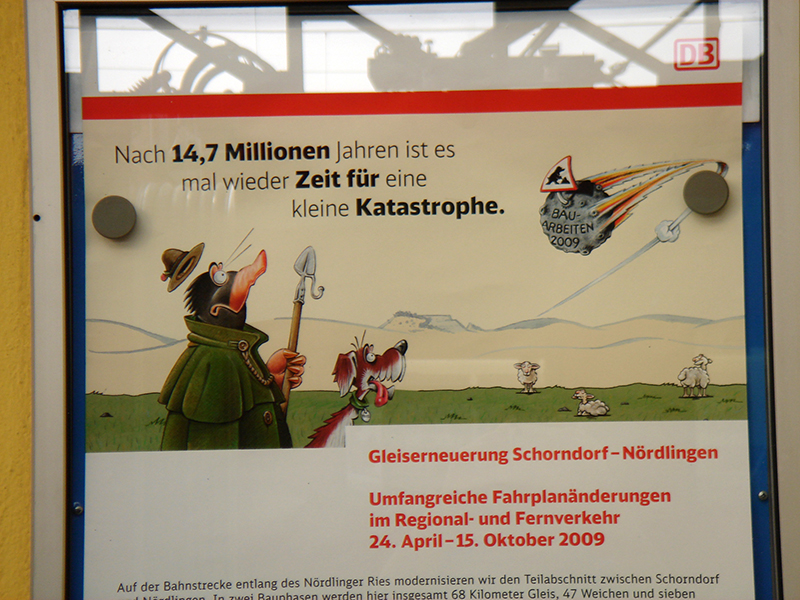

À partida de Nördlingen, um cartaz dos caminhos de ferro alemães mostrava que a cratera está perfeitamente integrada na cultura local. Recentemente, o parque candidatou-se ao estatuto de Geoparque da UNESCO; esperemos que tenham adoptado uma política linguística mais abrangente…

Aqui ficam alguns websites com mais informação sobre a grande cratera do Ries:

Site do Planetary Science Institute, com um tour virtual

Relatório da avaliação da candidatura do Ries a UNESCO Global Geopark

Nota: o autor do texto não escreve segundo o novo Acordo Ortográfico.

ENGLISH VERSION

This theme has four parts

Part 1 – Part 2 – Part 3 – Part 4

Places where the heavens fell on Earth – Part 2

September 2019. EPSC (the “European Planetary Science Congress”) had taken me to Germany, more precisely to Potsdam, near Berlin, a Prussian place of lakes, palaces and gardens. After the Congress, it was time to grab my backpack and cross a good part of Germany on a southbound train. Destination: Nördlingen, a small medieval town surrounded by a wall, to the north of Augsburg, and famous for contributing half of the name of a well-known crater: the Ries (the other half of the name, and more normally used).

If you look at a Google Earth image, it jumps right at you… doesn’t it? Yeah, right.

The local museum claims that it is the largest and best-preserved impact crater in Europe. Let’s agree on that. But, once again, on the ground, it isn’t easy to have that feeling of being inside an impact crater. Why? It’s a matter of size – it’s 24 km in diameter. And, again, it’s also a matter of age – almost 15 million years on a planet that does not rest. And that’s why the depression that was created by a cosmic object 1.5 km in size, at a speed of around 20 km/s – an impact that released as much energy as 1.8 million Hiroshima bombs – was later disguised by the materials that settled in the lake that occupied it. Thus, to see the whole crater, the only solution would be to rent a small plane… or look at a classic photograph taken from the air. On the other hand, if we see a model of the regional topography, we do have to agree: the crater jumps right up at you.

Nördlingen is surrounded by a circular wall – but those fortifications are 1 km in diameter, the size of the medieval town. It does not occupy the crater; in fact, it is located on the rim of the internal ring – the Ries is a complex crater.

Nevertheless, the town did play an important role in the recognition of the character of the crater. In the common fashion of the day, the initial explanations for the circular structure called upon volcanism – except there were no volcanic rocks around. Mystery.

Then, in 1960, Eugene Shoemaker and E.T. Chao came for a visit. He was a geologist who dreamed of becoming an astronaut and going to the Moon; unfortunately, a medical condition dashed his hopes of ever doing it. Instead, he became one of the creators of the Astrogeology Branch of the United States Geologic Service, geology instructor to the Apollo astronauts, and a man who never tired of looking for impact craters on Earth (he died in Australia, after a visit to a crater in the Outback). In between visits to quarries and other sites where the geology of the region could be probed, Shoemaker took notice of the town buildings; among these, the tall (90 m) bell tower of the church, that even has a name: The Daniel. And in the local stones that it had been built with there was the evidence of their impact origin – again, the suevite, with its glassy rock fragments that were melted when the crater was excavated and then cooled rapidly as they fell through the atmosphere, with no time to crystallise.

For someone with little time (and even less tim€) to explore the surrounding area, and after climbing the tower and seeing in the distance the elevations that mark the outer rim of the crater, the best way to get to know it was undoubtedly a careful visit to the dedicated museum, located at the Eugene Shoemaker Square.

Unfortunately, there was at the time no planned excursion to the geological interesting sites around the crater (I hadn’t yet made the acquaintance of some of the local scientists, that I would get to know a little more than a year later, while visiting another crater). The museum is very interesting, and detailed. They just “forgot” to provide information panels in English… So, my very limited knowledge of Goethe’s language left me just “looking at the pictures”.

Beyond the history of the crater (both geological and historical) and the samples of local rock types, there were assorted meteorites, and a piece of moon rock – astounded at the lack of measures for protection of that valuable sample, I asked if they were not concerned with the possibility of theft… I got only horrified looks – how could anyone, there, in the heart of Germany, even think of stealing such a prized piece? Well, the Portuguese sample (offered as a “goodwill sample” by the USA after the Apollo landings) has been long gone, and it’s far from being the only one.

Speaking of astronauts, one highlight of the museum is the reference to the visits made by some of them. Not for social reasons, but to have some geological training (with Shoemaker and others), as a preparation for lunar exploration.

Looking at the geological information, the complexity of the crater becomes easy to understand. In the outskirts of the crater, the impact generated a series of fractures, along which there happened a series of landslides, and on top of that, a large volume of ejected and brecciated material settled. Thus, the true rim of the crater is there, and it corresponds to the elevated ground that can be seen from the top of Daniel.

To conclude with the story of the Ries: around 40 kilometres to the southwest there is another, smaller, crater, called Steinheimer, of the same age. Is there a relation? Indeed, it is thought that the impactor had broken up, and that the smallest fragment, around 150 m in size, was responsible for that smaller crater. And, on top of that, the creation of the Ries led to an ejection of small drops of melted material that travelled further afield and spread to what is now the Czech Republic, where these tectites can be found and are known as moldavites.

Leaving Nördlingen, a poster from the German railway provided proof that the crater is perfectly integrated into local culture. In more recent times, the Park applied for the status of UNESCO Global Geopark; let’s hope they have by now adopted a more global language policy…

If you want to find out more about the great Ries crater, here are some links:

The Planetary Science Institute site, that offers a virtual tour

Evaluation report of the application of the Ries to become a UNESCO Global Geopark

Leave a Reply