Lugares onde o céu caiu em cima da Terra

Este tema está dividido em 4 partes:

Parte 1 – Parte 2 – Parte 3 – Parte 4

For English version click here

Autor: José Saraiva

José Saraiva é geólogo de formação. Licenciado pela Univ. Coimbra, fez um Mestrado no IST e por lá ficou muitos anos como bolseiro de investigação. Marte e outros planetas foram alvo de várias investigações sob o prisma da Análise de Imagem ao longo desses anos. Actualmente é Coordenador de Projectos no NUCLIO, de que é colaborador há muitos anos.

Introdução

Na Terra, existem centenas de crateras de impacto reconhecidas como tal; elas estão espalhadas por todos os continentes, embora não de forma homogénea. Algumas têm aquela morfologia característica de depressão circular, mas muitas não a possuem, porque a Terra é um planeta geologicamente activo, e isso altera rapidamente (à escala geológica) o aspecto da superfície… Tive a sorte de poder visitar algumas, na Europa, na América e na Ásia; é dessas visitas que esta série vai falar – com ênfase na experiência pessoal e não nos detalhes mais técnicos, que poderão ser interessantes, mas para uma faixa mais reduzida de leitores.

Lugares onde o céu caiu em cima da Terra – Parte 1

Agosto de 2008. Após uma viagem de algumas horas de autocarro pelas normalmente estreitas estradas norueguesas, chegávamos à Cratera de Gardnos.

O grupo era constituído pelos participantes na excursão ao local, organizada no quadro do IGC 2008 (o “33º Congresso Internacional de Geociências”). Excursão em que tinha conseguido participar com um bom bocado de sorte – não me tinha inscrito no devido momento, por razões burocráticas, e quando tentei fazê-lo no respectivo balcão no recinto do Congresso, a loura norueguesa que me atendeu disse que já não havia lugares – nem milagres. Normal, disse para com os meus botões, resignado – não estava à espera deles. Estava em Lillehammer (oficialmente, o congresso era o Oslo2008, mas Lillehammer fica a uma curta viagem de comboio da capital norueguesa), para fazer algumas apresentações relativas ao trabalho sobre crateras marcianas que então ocupava o grupo de que fazia parte no IST. Conheci vários membros do “grupo dos impactos”, fiz conversa… e no meio dela fiquei a saber que um deles, um sul-africano, estava inscrito na excursão, mas não podia ir, por ter uma reunião importante nesse dia. Eis que algo cai do céu à minha frente – negócio feito, com desconto e tudo, lá fiquei com o lugar dele. E assim, Gardnos, aqui vou eu. A minha primeira cratera de impacto “ao vivo e a cores”, à minha frente!

Hum… comecemos por aqui: Gardnos é, e não é, exactamente o nome do local. A região onde fica a cratera chama-se Garnås – mas foi adoptado o nome Gardnos, por ser mais fácil de usar em artigos e citações (sem o “a” com bolinha… que até se lê “o”), e por ser também a antiga forma de a designar.

Bom, chegados ao local, paramos numa encosta, e de mapa na mão o organizador local diz-nos que a cratera estava ali em frente, não se via por causa da névoa que cobria a paisagem… mas também por não ser exactamente uma cratera, um buraco redondo daqueles que se vêem na Lua, por exemplo.

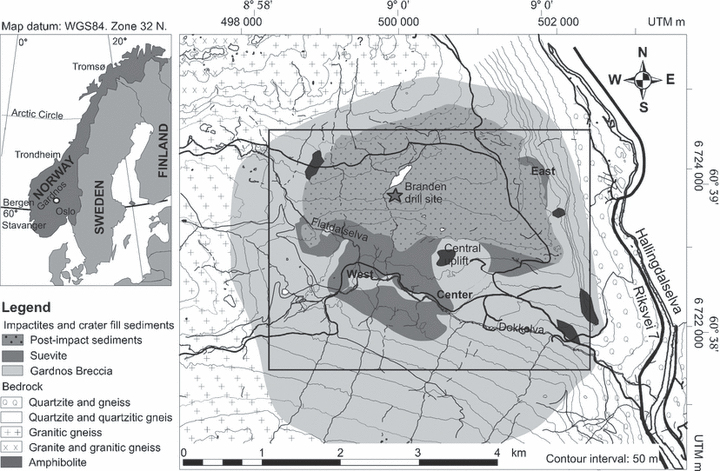

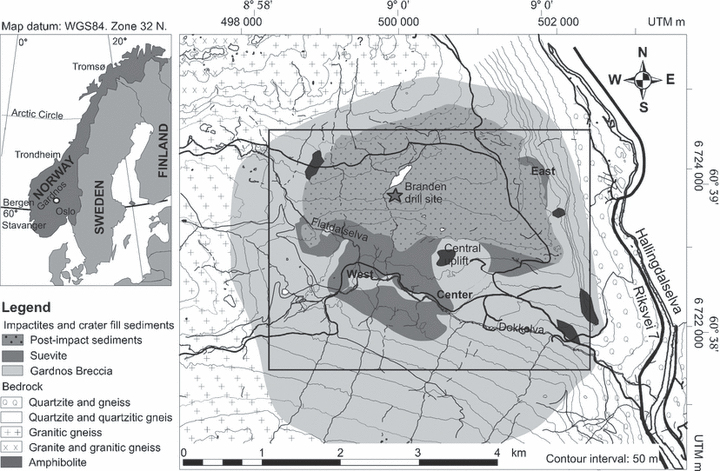

Era, sim, uma estrutura de impacto. A Escandinávia é uma zona antiga da superfície do nosso planeta (por isso é que há por lá tantas crateras…), e já passou por muita coisa: erosão, orogenias (formação de cadeias de montanhas), metamorfismo, glaciação, mais erosão, por aí fora. A idade da cratera de Gardnos não está bem estabelecida, embora seja por certo superior a 500 milhões de anos, e terá sido criada por um objecto metálico com algumas centenas de metros de dimensão, que embateu numa zona provavelmente coberta por uma extensão de mar pouco profundo. Hoje, os seus restos ocupam uma área de cerca de 5 km de diâmetro.

Como era costume, os primeiros estudos sobre a região apontavam para uma origem vulcânica, e só nos anos 90 foi proposto um processo de origem extra-terrestre.

Falta a pergunta dos 5 milhões de euros: mas então como é que se sabe que há ali de facto uma cratera? Na realidade, na Terra existem inúmeros processos geológicos que podem levar à formação de estruturas mais ou menos circulares com depressões no centro… e que não são crateras de impacto. Não é portanto pela morfologia do terreno que se pode ter a certeza quanto à origem do que parece uma cratera.

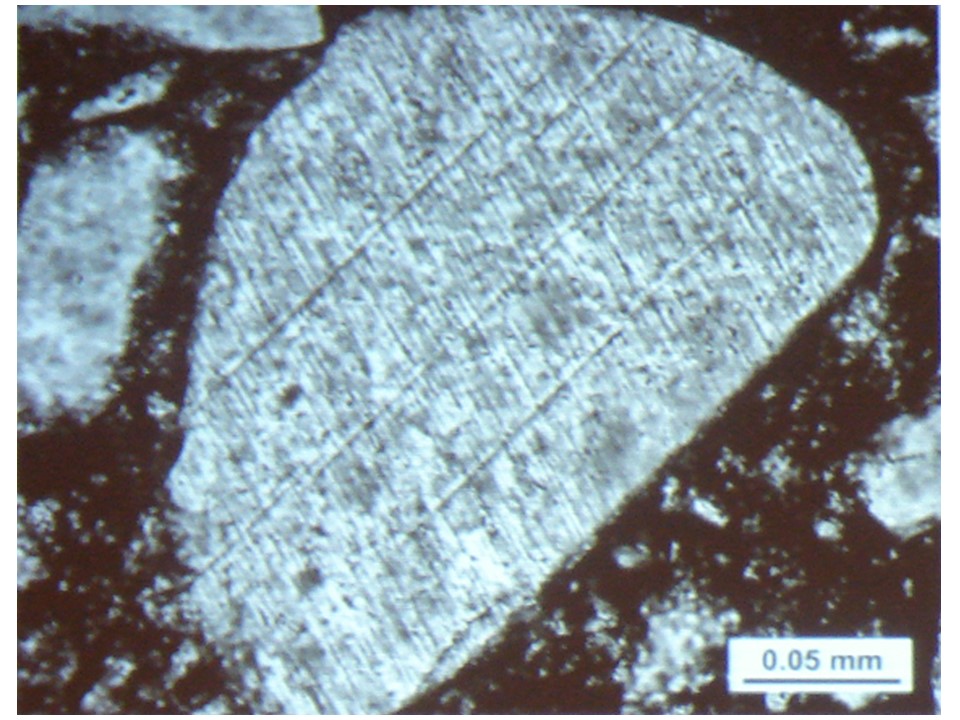

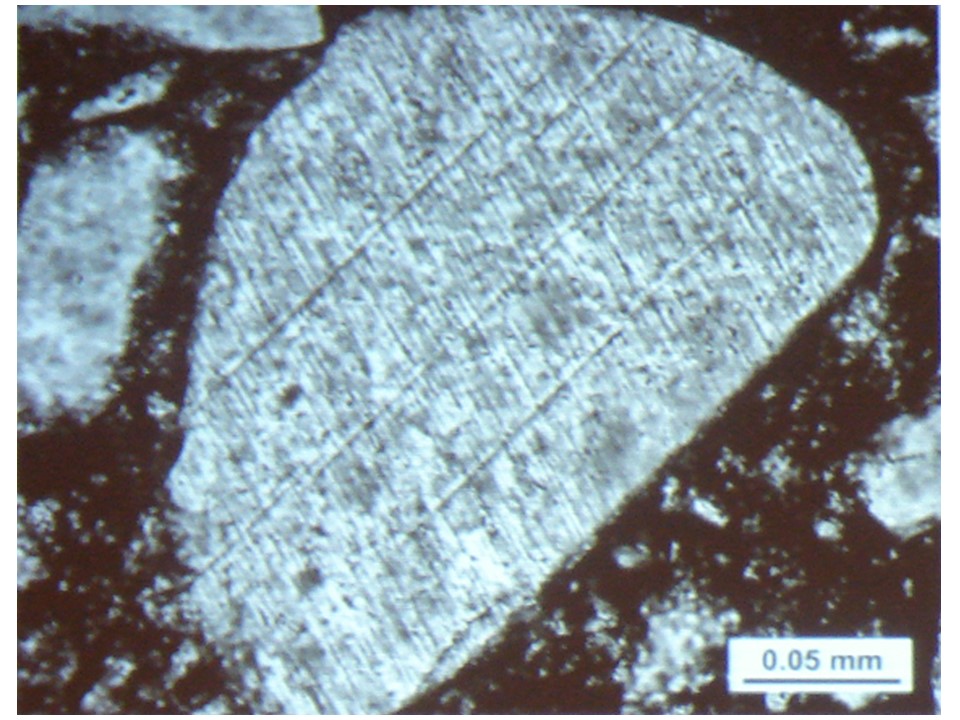

Sim, na Terra, a existência de uma cratera de impacto é confirmada pelas rochas; a nível macroscópico, pela presença de um tipo de rocha chamado suevito, e por estruturas como shatter-cones; mas, sobretudo, a nível microscópico, com a existência de PDFs (não são documentos electrónicos, e sim Planar Deformation Features) e minerais indicadores de altíssimas pressões, como a coesite (dióxido de silício, como o quartzo, mas com uma estrutura ligeiramente diferente, criada pelo choque de elevada energia).

Foi assim com Gardnos. Um estudo petrográfico detalhado encontrou os PDFs em cristais de quartzo, e tal foi o suficiente para ser proposta a origem da estrutura por impacto de um corpo extra-terrestre. Depois, no terreno, foram identificadas rochas – brecha de impacto, ou seja, a rocha que existia na região no momento do choque, mas completamente partida pela propagação da onda de choque; e suevito, que é também uma brecha que inclui clastos de todas as rochas da região, mas também fragmentos de material que foi fundido, voou pela atmosfera e voltou a tombar. A mais natural interpretação para a disposição estratigráfica destas rochas na área era a de que elas resultavam de um impacto. As provas foram-se acumulando, e hoje em dia esse encontro cósmico é aceite sem discussão – apesar de ter passado apenas pouco mais de meio século desde que a realidade da existência de cicatrizes de impactos na Terra se impôs, em simultâneo com a ideia de que o conceito de impactismo tem que ser considerado um processo geológico com o mesmo estatuto que outros.

O tempo estava húmido, e isso acabou por limitar as visitas no terreno. Ainda assim, com a capaz orientação dos colegas noruegueses, foram observados vários aspectos de relevo. Alguns dos participantes tinham ido munidos daquela ferramenta típica dos geólogos, o martelo – mas entre os pontos de paragem só num era autorizada a investigação própria à martelada…

Portanto, muitas fotografias, alguma discussão – onde há dois geólogos, é certo que haverá três opiniões – mas ali havia que respeitar os “donos” do terreno, que afinal eram quem mais o tinha estudado. Sim, vimos a brecha, o suevito, e também alguns dos sedimentos que ocuparam a cratera depois da escavação.

Por fim, uma curta paragem no centro de acolhimento aos visitantes – digamos que a “cratera” está bem explorada desse ponto de vista, incluída num “Parque meteorítico” – foi altura de comprar umas recordações (incluindo a obrigatória t-shirt). Tudo, menos uns frasquinhos com umas pequenas bolinhas acastanhadas, e um rótulo em norueguês. Se um dia forem a Gardnos, e alguém vos disser que são fragmentos do meteorito… não acreditem. Pela região vagueiam alces, e são eles os produtores certificados daquele material orgânico, que parece interessar alguns visitantes.

Em resumo: não foi uma visita a uma cratera facilmente identificável como tal. Se andasse pela região sem qualquer informação, nunca a encontraria. Mas foi uma visita educativa, e que deixou o apetite por mais.

Para os interessados, aqui fica uma curta publicação técnica sobre a cratera (de acesso livre):

Nota: o autor do texto não escreve segundo o novo Acordo Ortográfico.

ENGLISH VERSION

This theme has four parts

Part 1 – Part 2 – Part 3 – Part 4

Author: José Saraiva

José Saraiva trained as a geologist. He got a degree from the Univ. of Coimbra, and then an M. Sc. from IST (Technical University of Lisbon), where he spent long years as a project researcher. Mars and other planets, through the lens of Image Analysis, were the target of several researches during those years. Currently, he is a Project Coordinator at NUCLIO, after many years of collaboration.

Introduction

On Earth, there are hundreds of recognised impact craters; they are spread on all of the continents, though not homogeneously. Some do present that characteristic morphology of a bowl, a circular depression, but many others do not, since the Earth is a geologically active planet and that produces quick (on a geological timescale) changes to its surface… I had the good fortune of being able to visit a few, in Europe, America and Asia; this Theme of the Month will focus on those visits – from a personal point of view, leaving the technical details for the papers and books on the subject, that may interest some but not all of the readers.

Places where the heavens fell on Earth – Part 1

August 2008. After a couple of hours on a bus, traveling on the narrow Norwegian roads, we arrived at Gardnos Crater.

We were the participants of the excursion to the site organized as part of the IGC2008 (the “33rd International Geoscience Congress”). I had found a place thanks to a bit of luck – I had not registered before arriving in Norway, on account of bureaucratic reasons, and when I tried to do it over the counter at the Congress, a very blonde Norwegian lady let me know that there were no more places – and miracles were in very short supply. Nothing really unexpected, I dejectedly told myself, I wasn’t hoping for one. I was in Lillehammer (though the Congress was dubbed Oslo2008, Lillehammer was a short train trip from the capital of Norway), to make some presentations related to the work on martian craters that was the focus of the work being done by the group that I was part of, at the Technical University of Lisbon. I met several members of the ‘impact group’, engaged in conversation… and found out that one of them, a guy from South Africa, was registered for the excursion but wold not be able to make it, since he had an important meeting that he could not miss. Talk about something falling out of the sky right at my feet – made a quick deal, and got his place. And so, Gardnos, here I come. My first visit to an impact crater, live and in full colour, right in front of my eyes!

Erm… let’s start right here: Gardnos is, and is not, the precise name of the place. The area where the crater is located is called Garnås – but they opted for Gardnos, because it is easier to use on papers and citations (without the “a” with the little ring, which, anyway, is pronounced “o”), and also because that is the old designation of said area.

So, we arrive at the place, and we stop on a hillside; with a map in his hands, the local organizer tells us that the crater was right there in front of us, we just couldn’t see it on account of the mist over the landscape… and also because it wasn’t exactly a crater, a roundish hole as you can see on the Moon, for instance.

It was, in fact, an impact structure. Scandinavia is an old part of the surface of our planet (one of the reasons there are so many craters in there…), and it has seen many events: erosion, orogeny (the rising of mountain chains), metamorphism, glaciation, more erosion, and so forth. The age of the Gardnos crater is poorly constrained, though it is older than 500 million years, and it was created by an iron object sized in a few hundred metres, that crashed into what was probably a shallow sea-covered area. Today, what remains of the crater occupies a roughly circular area with a diameter of 5 km.

As usual, the earliest studies of the area pointed to a volcanic origin, and it was only in the 90’s that an extra-terrestrial process was proposed.

So, to the five-million euro question: how do we know that there is indeed there a crater? On Earth, there are a number of geologic processes that can lead to the formation of roundish structures with a depressed central area… and that are not impact craters. Thus, it is not the morphology of the terrain that one can be sure of the origin of what looks like a crater.

Yes, on Earth, the existence of an impact crater can only be confirmed by the rocks; on a macroscopic level, the tell-tales are the presence of a type of rock called suevite, and structures such as shatter-cones; but mostly, on the microscope, if PDFs (not digital documents, rather Planar Deformation Features) are found, along with (really) high pressure minerals such as coesite (silicium dioxide, as quartz, but with a slightly different structure induced by the high-energy crash).

That’s what happened in Gardnos. A detailed petrographic study found PDFs in quartz crystals, and that was enough for the authors to propose that the structure had been born as a result of the crash of a cosmic object. Then, in the field, some rocks were identified – an impact breccia, made of the rocks that were broken in place by the propagation of the shock wave in the ground; and suevite, also a breccia, but made of a mixture of clasts from the rocks, and including fragments that were melted, thrown out into the atmosphere and fell back. The most natural interpretation for the way those rocks were stratigraphically stacked in the area was that they resulted from an impact. As the evidence accumulated, the reality of that cosmic crash became accepted with no discussion – though it’s been only little more than half a century since the idea that there are on Earth clear markings of impacts was accepted, along with the concept that cratering should be considered a geologic process with the same relevance as others.

The weather was rather on the humid side, and that limited the field observations. Still, under the capable guidance of our Norwegian colleagues, many examples were located and pored over. Some of the participants had come with that most geological of tools, the hammer – but in fact hammering was not allowed in all points, except one…

So, many pictures were taken, discussions were held – anywhere you find two geologists, there will be at least three opinions – but at the same time there was a clear recognition that the locals were “in the know”, since they had deeply studied the area. And yes, we did see the breccia, the suevite, and some of the sediments that had occupied the crater right after it was excavated.

Finally, a quick stop at the visitor centre – the “crater” is rather well exploited, and is included in a “Meteoritic Park” – to get some mementos (the mandatory t-shirt, of course). Anything but the little flasks filled with brownish pellets, and a label in Norwegian. If by chance you happen to visit Gardnos, and someone tells you those are meteorite fragments… do not believe them. There are moose wandering around the area, and they are the certified producers of those organic samples, that indeed seem to attract some of the visitors.

In short, this was not a visit to a clear-cut impact crater. If you were left there with no indication, you would not find it. But it was educational, and left an appetite for more.

If you want to read a technical abstract about the Gardnos crater, see (freely available here):

Leave a Reply