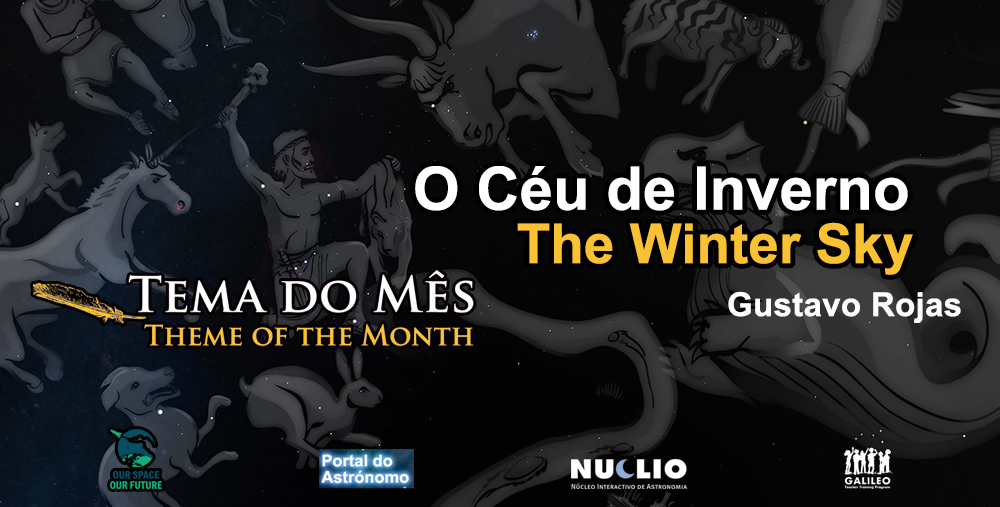

O céu de Inverno

O Céu de Inverno

As noites longas e frias do inverno não são muito convidativas para a observação do céu. No entanto, quem desafia o desconforto térmico é recompensado por vistas magníficas das brilhantes constelações da estação.

Os principais destaques na observação celeste nos próximos meses incluem belas conjunções planetárias, e algumas chuvas de meteoros de atividade moderada. Sobretudo, é a época ideal para explorar as brilhantes nebulosas encontradas nas constelação de Orion, e contemplar a maior galáxia da nossa vizinhança cósmica: M31, a Grande Espiral de Andrômeda.

Neste tema do mês, veremos os principais fenômenos astronômicos dos próximos meses, suas constelações características, e objetos celestes de interesse. Pegue um bom agasalho, enfrente o frio, e olhe para o céu!

Autor: Gustavo Rojas

Doutor em Astronomia pela Universidade de São Paulo (2008), Gustavo Rojas iniciou sua carreira profissional na Universidade Federal de São Carlos, Brasil. Atua há mais de 10 anos nas áreas de divulgação científica e ensino de ciências. É membro da União Astronômica Internacional, Sociedade Astronômica Brasileira, e Sociedade Portuguesa de Astronomia. Faz parte da comissão organizadora da Olimpíada Brasileira de Astronomia e Astronáutica, e foi líder das delegações brasileira (2012-2018) e portuguesa (2019) na Olimpíada Internacional de Astronomia e Astrofísica (IOAA). Foi representante brasileiro do ESO Outreach and Science Network de 2011 a 2018. Atualmente é coordenador de projetos no NUCLIO – Núcleo Interactivo de Astronomia.

Nota: o autor do texto escreve em português do Brasil.

⬇︎ Clique, abaixo, para ler cada uma das partes deste tema

O Céu Inverno – Parte 1

Afinal, quando é o inverno?

Na astronomia, o início do inverno é marcado pelo solstício de dezembro, quando o Sol atinge a posição mais ao sul na esfera celeste. Nessa data, temos o dia mais curto do ano no hemisfério norte. No entanto, as menores temperaturas geralmente são registradas um ou dois meses mais tarde. Em 2020, o solstício aconteceu em 21 de dezembro às 10:02 (hora de Portugal).

Constelações típicas

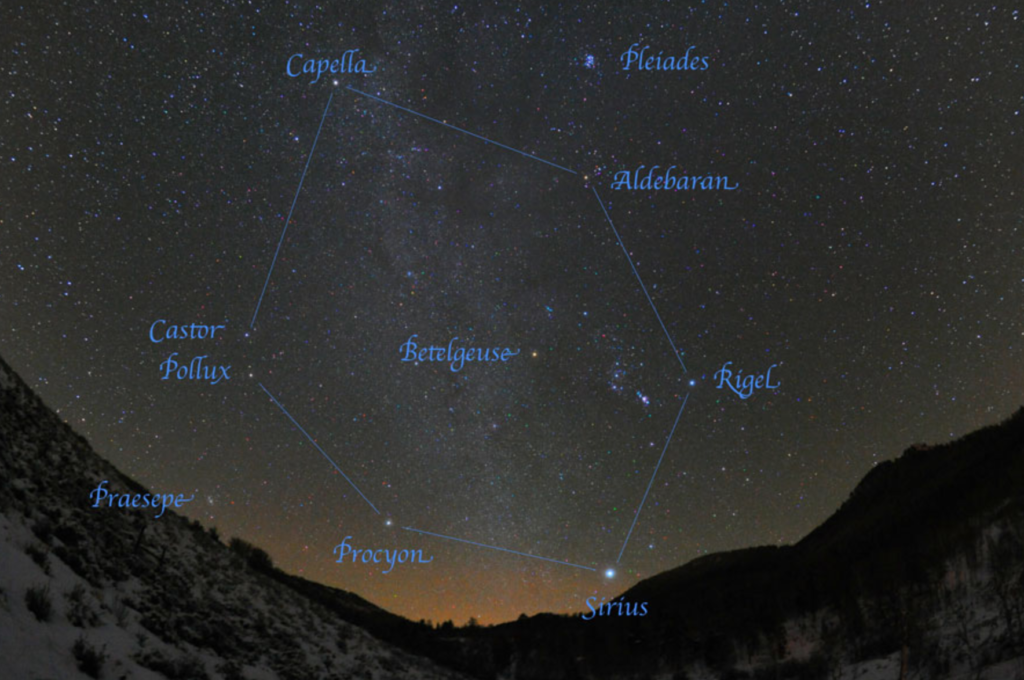

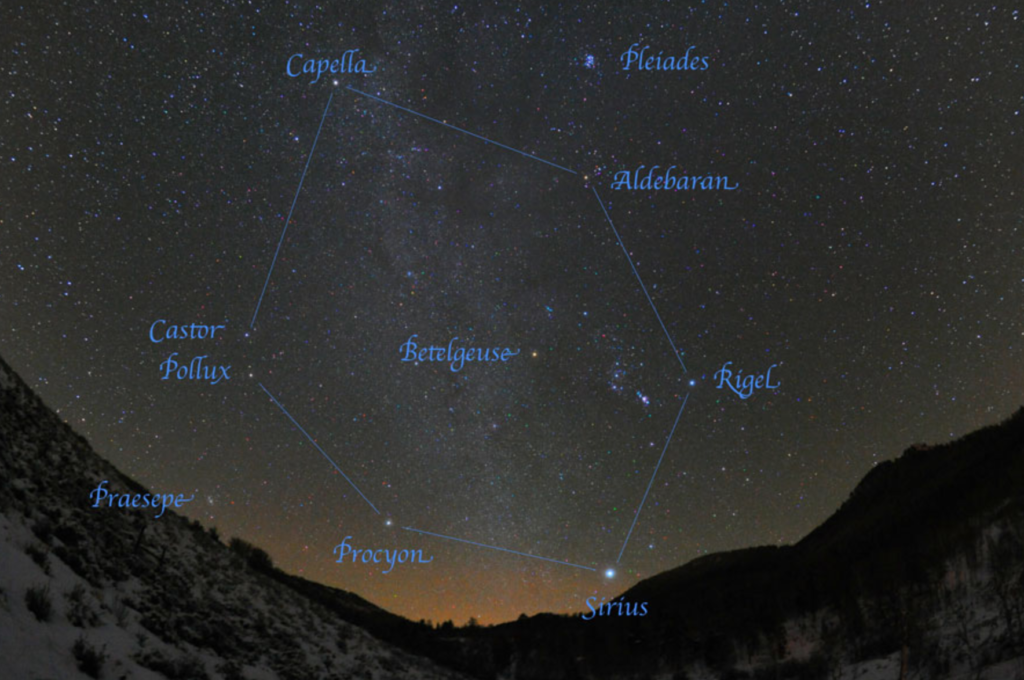

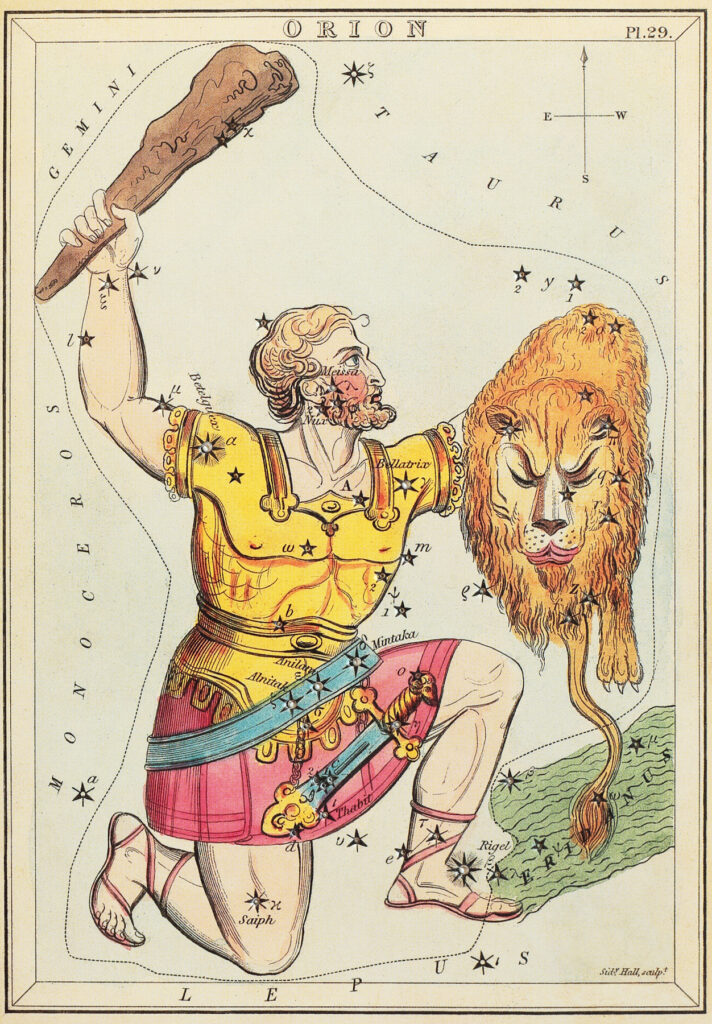

No hemisfério norte, o céu do inverno é marcado pelo chamado Hexágono do Inverno, formado pelas estrelas brilhantes Rigel, Aldebaran, Capella, Pollux, Procyon e Sirius. Estas estrelas indicam algumas das principais constelações da estação: Orion, Touro, Cocheiro, Gêmeos, Cão Menor, e Cão Maior.

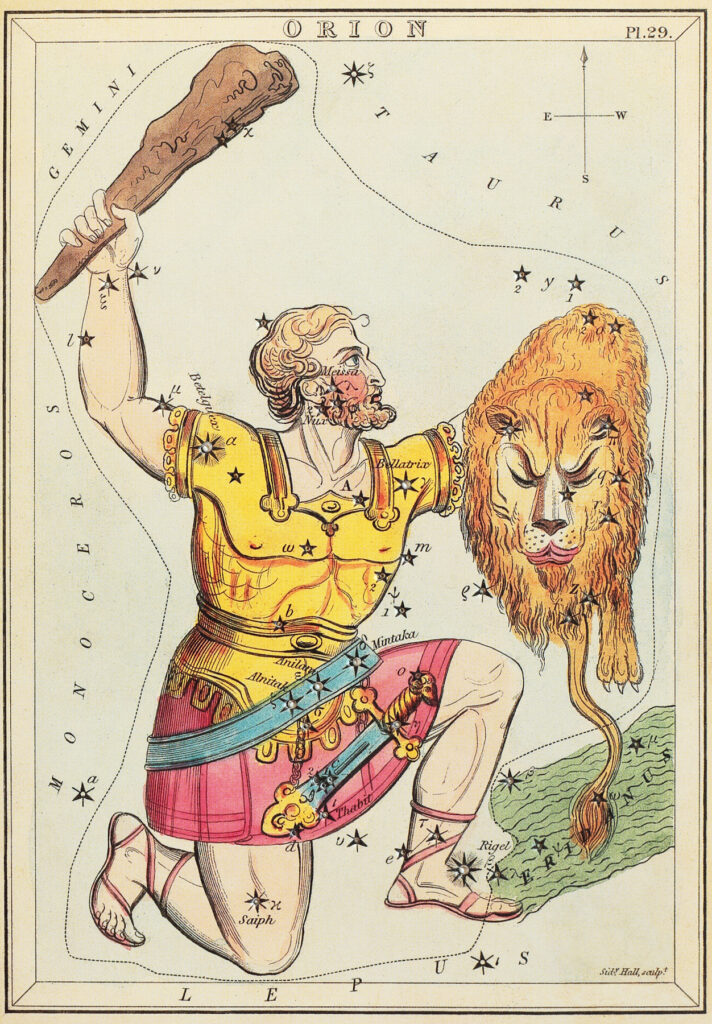

Destas, destaca-se Orion, uma das mais conhecidas constelações do firmamento. Sua figura é facilmente reconhecível pelo grande quadrilátero com vértices em Bellatrix, Betelgeuse, Rigel e Saiph. Ao centro, o inconfundível trio de Alnitak, Alnilam e Mintaka formam o asterismo das Três Marias. Conhecida em todo mundo, Orion tem vários mitos interessantes em diferentes culturas.

A lenda mais conhecida vem da cultura greco-romana. Em uma das versões da lenda grega, Orion era um gigante caçador, filho de Poseidon, o deus dos mares, com uma mortal.

Orion conheceu a deusa grega da caça, Ártemis, que era irmã do deus da razão, Apolo. Ártemis e Orion tornaram-se amigos e se apaixonaram, despertando ciúmes em Apolo. Para matar Orion, Apolo enviou um escorpião gigante para picá-lo.

Tentando fugir do escorpião, Orion entrou no mar, ficando apenas com a cabeça para fora. Percebendo isso, Apolo desafiou Artemis a acertar com uma flecha um ponto escuro no mar, que na verdade era a cabeça de Orion. Ártemis acertou, matando Orion. Ao perceber o que havia feito, Ártemis pediu a Zeus para que colocasse Orion no céu.

Zeus atendeu ao pedido, entretanto colocando também o escorpião no céu. Esse seria o motivo pelo qual Orion e Escorpião nunca aparecem juntos no céu: Orion está sempre a fugir do escorpião.

Já para os povos indígenas brasileiros, as estrelas de Orion fazem parte de uma constelação maior, o Homem Velho, que inclui também o vizinho Touro. A lenda Guarani conta que o Homem Velho casou-se com uma mulher muito mais nova, que ficou interessada em seu jovem cunhado e matou seu esposo, cortando sua perna na altura do joelho direito.

Os deuses ficaram com pena do homem e o transformaram em uma constelação, com Betelgeuse indicando o ponto em que sua perna foi cortada. A cabeça do Homem Velho é formada pelas estrelas de Touro: o enxame das Híades forma o rosto, e acima dela está um penacho, indicado pelo enxame das Plêiades.

A principal atração da constelação é a Grande Nebulosa de Orion, indicada pelo número 42 no catálogo de Messier. Distante 1340 anos luz da Terra, M42 é conhecida desde a antiguidade. Ela pode ser vista a olho nu até mesmo em regiões urbanas, como uma pequena mancha esfumaçada na região da espada dessa figura mitológica.

Com um binóculo ou pequeno telescópio já é possível perceber melhor a natureza gasosa da nebulosa. Com aumentos modestos de 30 vezes ou mais já se consegue separar as estrelas mais brilhantes do aglomerado do Trapézio, bem no coração da nebulosa.

O Trapézio recebe este nome por causa da figura geométrica formada por suas quatro estrelas mais brilhantes. Cada uma delas é uma supergigante azul com dezenas de vezes a massa do nosso sol. A luz ultravioleta dessas estrelas excita o gás da nebulosa, fazendo-a brilhar intensamente

No total, estima-se que a nebulosa contenha material para dar origem a centenas de milhares de estrelas como o Sol. Este processo, porém, é muito lento comparado com a escala de tempo humana. Uma estrela como o Sol, por exemplo, leva alguns milhões de anos para se formar. Por causa disso, acredita-se que M42 ainda irá brilhar por pelo menos mais um milhão de anos.

Graças à sua proximidade e dimensão, a nebulosa de Orion é a região de formação estelar mais bem estudada pelos astrônomos. Nela, foram observadas as etapas iniciais da formação estelar, como proplídeos, objetos Herbig-Haro e discos protoplanetários.

Messier também catalogou uma outra nebulosa em Orion muito próxima a M42, que recebeu o número seguinte no catálogo. M43 também é conhecida como Nebulosa de De Mairan, em homenagem ao seu descobridor, o também francês Jean Jacques De Mairan.

A rigor, M43 faz parte da Grande Nebulosa de Orion. Porém, parece ser um objeto independente graças à presença de uma espessa faixa de poeira que separa visualmente as duas nebulosas. Portanto, compartilha as mesmas características gerais da sua irmã mais famosa.

M43 também é uma região de intensa formação estelar. A nebulosa brilha graças à radiação ultravioleta emitida pelas suas estrelas mais massivas, em particular o sistema triplo NU Orionis.

M42 e M43 fazem parte de uma estrutura ainda maior conhecida como Grande Complexo Molecular de Orion. Esta gigantesca acumulação de gás e poeira estende-se por mais de mil anos luz e

engloba um grande número de nebulosas bem conhecidas.

Dentre os objetos que fazem parte desse complexo destaca-se a incrível Barnard 33, mais conhecida como Nebulosa da Cabeça de Cavalo. A alcunha vem da silhueta curiosa criada pela poeira à frente da nuvem de gás brilhante, cuja coloração avermelhada é originária do hidrogênio, que brilha excitado pela estrela quente Sigma Orionis.

A Nebulosa da Cabeça do Cavalo é uma das imagens mais icônicas da astronomia, e já foi cenário de muitas obras de ficção científica, incluindo O Guia do Mochileiro das Galáxias. É na nebulosa que fica o planeta Magrathea, onde estaria a civilização que construiu a Terra.

Observar a Cabeça do Cavalo requer céus muito escuros e um telescópio de pelo menos 20 cm de abertura. Filtros especiais para observação de nebulosas podem ajudar. Com esse equipamento, basta procurá-la próximo à estrela Alnitak, a mais ao leste das Três Marias.

Completando a lista de objetos de Messier em Orion temos M78. Assim como suas vizinhas M42 e M43, M78 também faz parte da enorme estrutura conhecida como Complexo Molecular de Orion, uma gigantesca nuvem molecular de mais de mil anos luz de extensão.

M78 é o objeto mais brilhante do grupo que também inclui as nebulosas NGC 2064, NGC 2067 e NGC 2071. Pode ser localizada com telescópios de pequeno porte, na região entre a gigante vermelha Betelgeuse e Alnitak.

A região de M78 contém um grande número de estrelas em formação, incluindo dezenas estrelas variáveis do tipo T Tauri, que ainda têm ao seu redor discos de poeira onde planetas estão a se

formar. Fotografias de longa exposição revelam uma intrincada variedade de regiões de emissão, reflexão e absorção, manifestações do gás e poeira associados ao fenômeno de formação estelar.

Outro objeto bastante interessante associado com M78 é NGC 2024, mais conhecida pelo seu nome popular de Nebulosa da Chama. Esta nebulosa também está muito próxima da estrela Alnitak.

Assim como sua vizinha Nebulosa da Cabeça de Cavalo, a Nebulosa da Chama é um alvo predileto dos astrofotógrafos, mas é de difícil visualização com telescópios. Somente instrumentos de grandes

aberturas permitem apreciar todo o esplendor dessa região de formação estelar.

O que ver no céu em janeiro

2/1: A Terra mais perto

Nosso percurso anual ao redor do Sol não se faz em uma trajetória circular. A órbita terrestre é ligeiramente ovalada, e como resultado, a distância Terra-Sol varia ligeiramente ao longo do ano. A aproximação máxima, chamada periélio, acontece em janeiro e mede aproximadamente 147,1. milhões de km. Em julho, é a vez de ficarmos alguns milhões de quilômetros mais longe da nossa estrela. Este ponto na órbita é conhecido como afélio, e nele a distância até o Sol atinge 152,1 milhões de quilômetros.

Embora 4 milhões de quilômetros seja um número extremamente grande (mais de 10 vezes a distância até a Lua), não podemos perceber qualquer variação do tamanho aparente do Sol. Apenas em registros fotográficos é que essa diferença de cerca de 3,5% pode ser notada.

3/1: Meteoros Quadrantídeos

A primeira chuva de meteoros do ano leva o nome de uma constelação extinta: Quadrans Muralis, proposta pelo francês Jerôme Lalande no século XVII. A constelação simbolizava um grande instrumento usado para medir ângulos no céu, mas nunca foi adotada nos mapas celestes modernos.

Apesar disso, esta sugestão de Lalande ainda é utilizada até hoje para designar a chuva de meteoros Quadrantídeos, cujo radiante fica situado na área atualmente ocupada por Boieiro e Dragão. Esta chuva foi observada pela primeira vez em meados de 1830 na Europa e na América do Norte.

Para observar os Quadrantídeos, olhe para o norte, na direção da estrela Arcturus, a alfa do Boieiro, no final da madrugada. Não é uma chuva espetacular, mas em condições ideais podem ser vistos até 30 meteoros por hora.

24/1: Mercúrio em Máxima Elongação

Mercúrio atinge seu maior afastamento com relação ao Sol, brilhando com magnitude aparente -0,7. Pode ser visto no horizonte Oeste após o pôr do Sol, na fronteira entre as constelações de Aquário e Capricórnio.

Na próxima Semana …

O Tema do Mês continua com mais curiosidades das constelações do inverno, e as dicas de observação para fevereiro. Até breve!

O Céu de Inverno – Parte 2

Cães Celestes

Ao redor de Orion encontramos outras duas constelações típicas do inverno, que simbolizam os cães do gigante caçador.

A maior e mais brilhante é o Cão Maior, cuja cabeça é simbolizada por Sirius, a estrela mais brilhante do céu. Outras duas estrelas bastante brilhantes ajudam a formar a figura do animal. Em sua pata está a estrela Mirzam, nome árabe que significa “a anunciadora”, já que essa estrela aparece no céu um pouco antes de Sirius.

Do outro lado, formando as costas do cão, está a estrela Wezen, nome também de origem árabe, que significa “pesada”. Curiosamente, Wezen é de fato uma estrela bastante massiva, com mais de 10 vezes a massa do nosso Sol.

Bem menos impressionante é a constelação do Cão Menor, que possui apenas uma estrela brilhante, Procyon. É uma estrela bastante próxima de nós estando a apenas 11 anos luz de distância. Essa também é a 8ª estrela mais brilhante do céu, formando um triângulo com Sirius e Betelgeuse, a estrela avermelhada de Orion.

Devido a seu brilho, Sirius tem lugar de destaque nas culturas do mundo. A alfa da constelação do Cão Maior foi venerada pelas civilizações antigas em todos os continentes, que lhe batizaram com mais de 50 nomes diferentes.

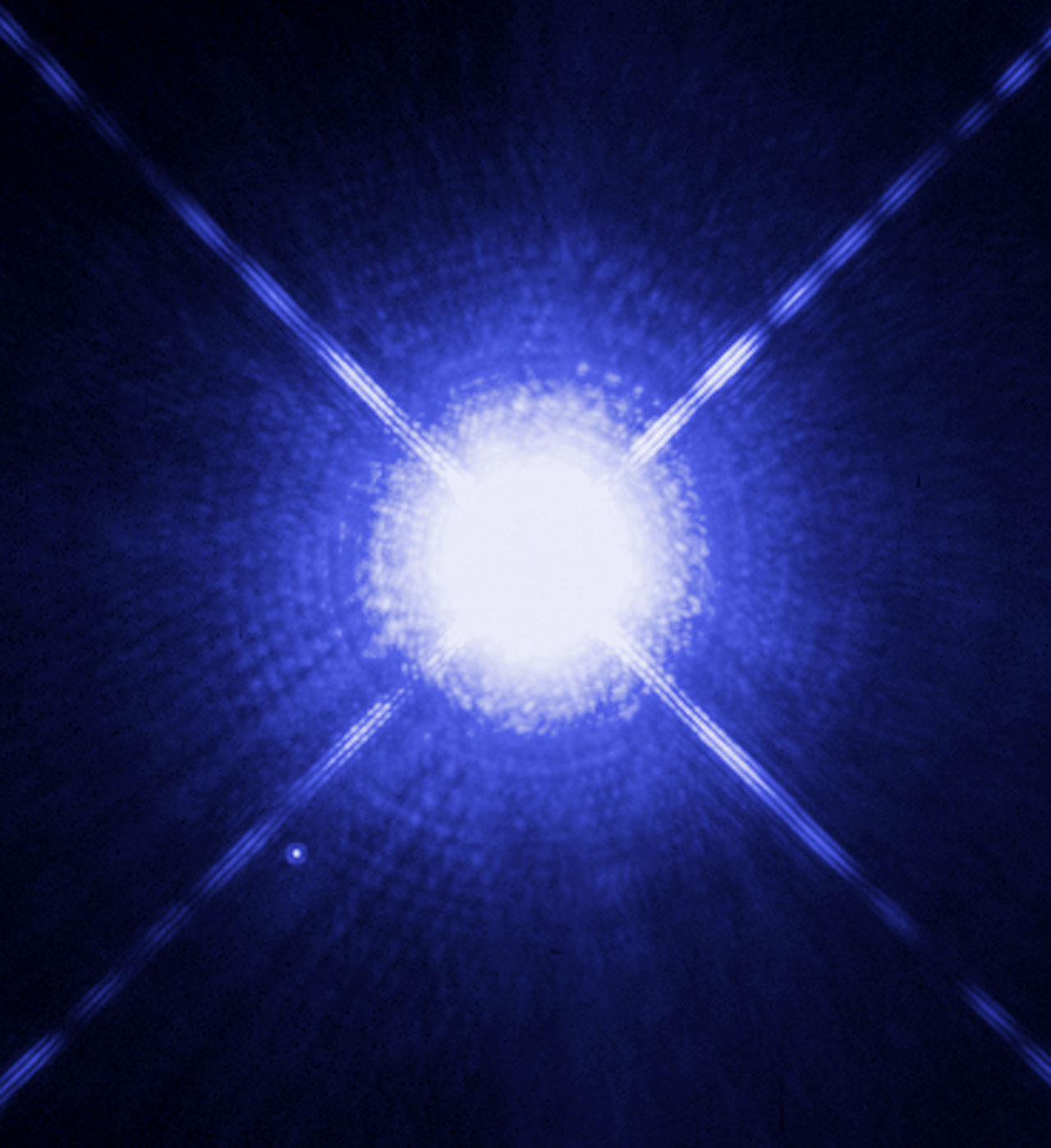

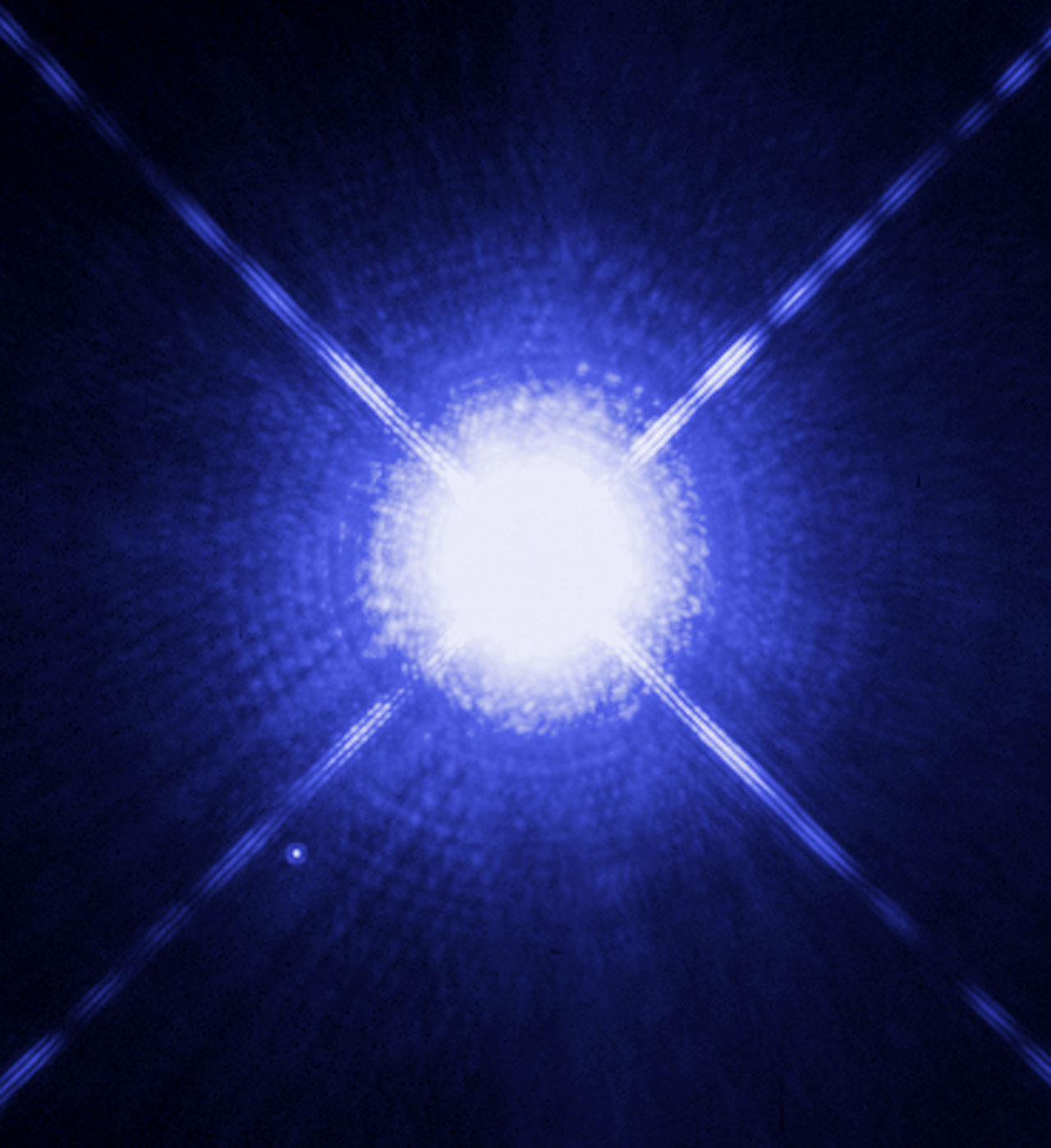

Uma das estrelas mais próximas de nós, Sirius também desperta o interesse dos astrônomos. No século 19, o famoso fabricante de telescópios americano Alvan Clark descobriu a fraca estrela companheira de Sirius, inspirado nos cálculos feitos pelo astrônomo alemão Friedrich Bessel.

Sirius B, como foi chamada, é uma das maiores anãs brancas conhecidas. Possui quase a mesma massa do Sol, mas compactada em um volume similar ao da Terra.

Essa impressionante densidade é resultado da evolução estelar de uma estrela com cinco vezes a massa do Sol, que consumiu todo o hidrogênio em seu núcleo em pouco mais de 100 milhões de anos. É o que restou dessa evolução, um núcleo exaurido de carbono e oxigênio, com temperatura superficial de 25 mil graus.

Sirius B faz parte de uma controvérsia envolvendo uma primitiva etnia africana. Os Dogons, povo que habita a chapada de Bandiagara em Mali, possuem uma interessante cosmologia envolvendo espíritos chamados Nommo.

Na década de 1930, dois antropólogos franceses que viveram com os Dogons publicaram impressionantes relatos. De acordo com eles, os espíritos Nommo eram habitantes do sistema de Sirius, e passaram aos Dogons avançados conhecimentos de astronomia, incluindo o tamanho, densidade e período orbital de Sirius B.

A história ganhou notoriedade na década de 1970, quando o escritor Robert Temple escreveu o livro Mistério de Sirius. Nessa obra, ele tenta associar o relato dos antropólogos franceses a um suposto contato dos Dogons com extraterrestres, que teriam passado informações sobre a existência da anã branca.

Embora fantástica, essa hipótese não foi bem recebida pelos astrônomos e antropólogos, que não encontraram evidências convincentes. Como já disse Carl Sagan, alegações extraordinárias exigem provas extraordinárias.

A explicação mais provável é que o povo Dogon tenha adquirido essas informações com missionários europeus que visitaram o Mali no final do século 19, sendo rapidamente incorporadas à sua tradição oral. Será essa a resposta para o Mistério de Sirius? Talvez nunca saibamos a resposta …

Também em Cão Maior está uma das estrelas mais luminosas já descobertas, e que durante muito tempo deteve o recorde de maior estrela conhecida.

VY Canis Majoris é uma hipergigante vermelha a 4 mil anos luz da Terra. Está associada a uma região de formação estelar junto ao aglomerado NGC 2362. É uma estrela muito jovem, formada há poucos milhões de anos mas que já se encontra numa fase avançada de sua evolução.

Inicialmente uma hipergigante azul de pelo menos 15 massas solares, ela consumiu rapidamente o hidrogênio em seu núcleo. Como consequência, sofreu uma grande expansão e resfriamento de suas camadas externas.

VY Canis Majoris emite quase 300 mil vezes mais energia que o Sol. Estima-se que sua temperatura superficial seja de aproximadamente 3500 graus, o que resulta em 1420 diâmetros solares. Se colocada no lugar do nosso Sol, VY Canis Majoris engoliria todos os planetas até Júpiter! Sua superfície se estenderia por quase 7 unidades astronômicas, o equivalente a 1 bilhão de quilômetros!

Mesmo com esse tamanho impressionante, ela não é mais a maior estrela conhecida, tendo sido superada por outras hipergigantes como RW Cephei e UY Scuti, a atual recordista com 1700 raios solares.

Você pode observar VY Canis Majoris com um telescópio amador. É uma estrela fraquinha, de magnitude 8, e que forma um triângulo com as estrelas Wezen e Aludra. Um belo desafio para esse começo de ano.

Curiosamente, em Cao Maior existe apenas um objeto de céu profundo presente no catálogo de Messier. Em compensação, é um espetacular enxame aberto.

Messier 41 é conhecido dos astrônomos há bastante tempo. É brilhante o suficiente para ser observado a olho nu em locais de céu bem escuro. Sua primeira aparição num catálogo astronômico foi em 1654, na relação compilada pelo italiano João Batista Hodierna. O inglês John Flamsteed também registrou o enxame no seu Catálogo Britânico em 1702.

M41 é um enxame razoavelmente jovem, formado há 190 milhões de anos. Contém cerca de 100 estrelas reunidas num diâmetro de 25 anos luz, incluindo algumas gigantes vermelhas e anãs brancas. Está aproximadamente à mesma distância de nós de outro enxame chamado Collinder 121. Alguns astrônomos suspeitam que os dois aglomerados possam ter uma origem comum, mas essa é uma hipótese que ainda está sendo estudada.

M41 é um aglomerado de fácil localização, formando um triângulo com Sirius e a estrela Nu Canis Majoris. Pode ser observado facilmente com binóculos.

O que ver no céu em fevereiro

18/2 A Lua encontra Marte

Nessa noite, a Lua em quarto crescente posiciona-se logo abaixo do planeta vermelho. O par pode ser observado a sudoeste na primeira metade da noite.

24/2 Lua na Colmeia

A Lua quase cheia passa próxima ao enxame da Colmeia (Messier 44), na constelação de Cancer. Use binóculos para localizar o enxame abaixo da Lua e observar dezenas de estrelas.

Na próxima semana …

O Tema do Mês continua a visitar as constelações típicas do inverno, e dá dicas de observação do céu para março. Até breve!

O Céu de Inverno – Parte 3

Fechando o Hexágono

O inverno é caracterizado pelo conjunto de estrelas brilhantes que formam a figura conhecida como Hexágono de Inverno. Já falamos de três constelações cujas estrelas compõem o asterismo: Orion (Rigel), Cão Maior (Sirius) e Cão Menor (Procyon). Nessa semana vamos visitar as constelações que faltam.

Seguindo ao norte de Procyon, no Cão Menor, chegamos à primeira constelação de interesse: Gêmeos, onde estão as estrelas Castor e Pollux.

Gêmeos Celestes

Esse par de estrelas de brilho semelhante torna essa uma das constelações zodiacais mais fáceis de se identificar.

Os primeiros catálogos de estrelas, como o feito no século 4 por Ptolomeu, indicavam as estrelas com o mesmo brilho. Quando Johann Bayer atribuiu as letras gregas às estrelas em 1603, Castor ainda constava como mais brilhante. Somente no século XIX que Pollux passou a ser reconhecida como a mais brilhante da constelação. Não sabemos o porquê dessa discrepância.

As estrelas têm colorações distintas. Pollux tem um leve tom alaranjado. Já Castor é branca e, quando vista ao telescópio, revela-se como uma estrela dupla. Inclusive, Castor foi o primeiro sistema estelar identificado como binário, quando foi estudado por William Herschel. Ele descobriu que elas orbitam em volta do centro de massa do sistema com um período de 420 anos.

Estudos posteriores mostraram que cada um desses componentes é também uma estrela dupla, muito próximas para serem resolvidas com telescópios, mas detectáveis pela espectroscopia. Existe ainda um terceiro par de estrelas pertencente ao sistema, mais afastado, conhecido como YY Geminorum. Isso torna Castor um raro sistema estelar sêxtuplo.

Em Gêmeos encontramos apenas um objeto de Messier. M35 foi descoberto na metade do século 18 de maneira independente pelos astrônomos John Bevis e Philip de Cheseaux, e mais tarde incorporado por Charles Messier em seu famoso catálogo.

Esse enxame está distante 2800 anos luz da Terra e é razoavelmente jovem para os padrões astronômicos. Formado há 150 milhões de anos, M35 ainda mantém parte do gás e poeira de sua formação ao seu redor, evidenciados pela luz espalhada de suas estrelas mais brilhantes.

O enxame é bastante extenso, e melhor observado com instrumentos de baixo aumento. Mesmo um instrumento de menor abertura pode revelar quase uma centena de estrelas. No total, M35 possui cerca de 2500 membros concentrados em um diâmetro de 30 anos luz.

Na mesma região do céu encontramos também o enxame NGC 2158. Apesar da aparente proximidade, os dois enxames não têm qualquer conexão entre si. NGC 2158 está quatro vezes mais distante e é bem mais antigo que M35.

Com quase 2 mil milhões de anos de idade, NGC 2158 foi inicialmente classificado como enxame globular, mas hoje sabemos que é na realidade um enxame aberto bastante evoluído. Sua idade avançada é indicada pela ausência de estrelas azuis, que evoluem mais rapidamente e explodem depois de algumas centenas de milhões de anos. Enxames antigos como NGC 2158 apresentam uma população quase inteiramente composta de estrelas avermelhadas.

Para localizar esse curioso par no céu, aponte seu binóculo ou telescópio para a região da estrela Eta Geminorum. Esta estrela forma o pé esquerdo de um dos gêmeos da constelação, cuja cabeça é marcada por Castor.

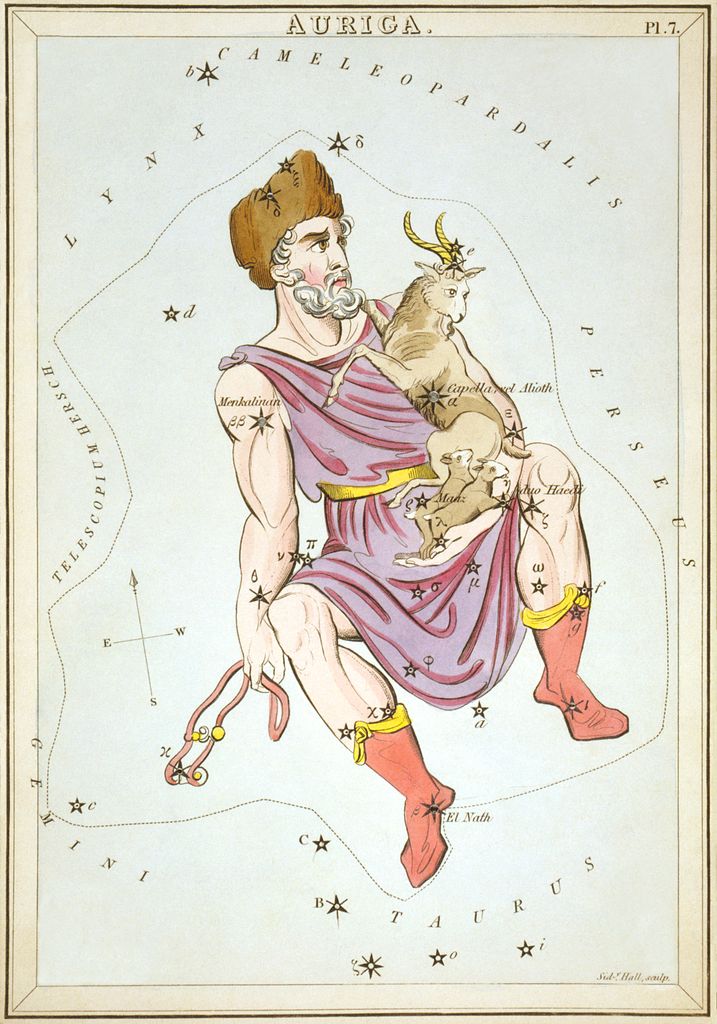

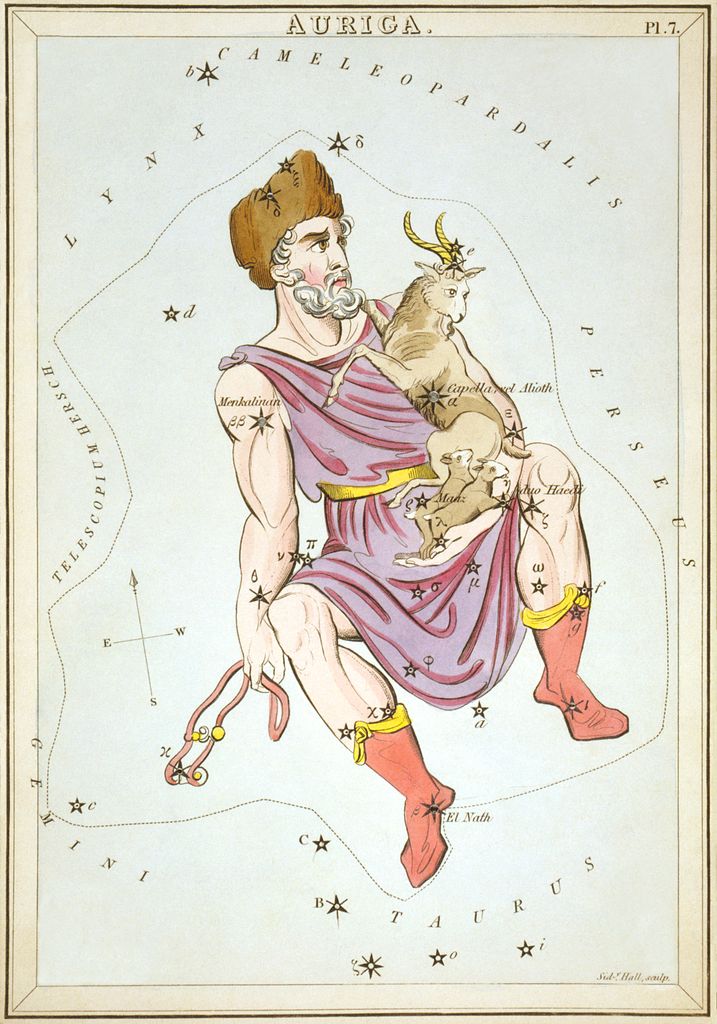

A Carroça e a Cabra

Ao norte de Gêmeos está a constelação do Cocheiro. Sua estrela mais brilhante, Capella, é um dos vértices do hexágono. Capella é a sexta estrela mais brilhante do céu, e a estrela de primeira grandeza mais próxima do pólo celeste norte. Desde a época da Mesopotâmia ela já era associada a uma cabra. De fato, o nome Capella significa “pequena cabra” em Latim, uma referência à cabra Amalteia, que teria amamentado Zeus.

A constelação do Cocheiro representa o condutor de uma pequena carroça, acompanhado por cabras. Além de Capella, as estrelas Zeta e Eta Aurigae também representam estes animais. Esse par é conhecido como “Haedi”, que quer dizer “cabritos” em Latim.

Capella é na verdade um sistema estelar quádruplo, composto por duas gigantes amarelas e duas anãs vermelhas. As gigantes amarelas possuem cada uma 3 vezes a massa do Sol, e juntas brilham 140 vezes mais que nossa estrela.

O sistema de Capella está bastante próximo da Terra para os padrões astronômicos, apenas 40 anos luz daqui. Essa proximidade rendeu lugar de destaque entre os escritores de ficção científica, sendo palco de um episódio da série Star Trek.

Capella é também assunto de um conhecido livro de espiritismo. No entanto, até o momento não foi detectado nenhum planeta orbitando os quatro componentes de Capella.

O que sabemos é que as gigantes amarelas já se encontram num estágio avançado de sua evolução, e que dentro de alguns milhões de anos irão se expandir ainda mais, tornando-se gigantes vermelhas. Continuará sendo uma das estrelas mais brilhantes do céu durante muito tempo.

No Cocheiro encontramos 3 objetos do catálogo de Messier: os enxames M36, M37 e M38. Estes enxames têm idades variadas. O mais jovem é M36, com apenas 25 milhões de anos. Com várias estrelas azuladas, sua aparência ao telescópio lembra bastante as famosas Plêiades.

M38 é de idade intermediária. Formado há aproximadamente 300 milhões de anos, já não apresenta as luminosas estrelas azuis, mas ainda contém um grande número de estrelas amarelas como o nosso Sol.

M37 é o mais antigo dos objetos de Messier no Cocheiro. Foi formado há 500 milhões de anos, e conta com pelo menos 500 estrelas, sendo que algumas já atingiram a fase de gigante vermelha. Está localizado na direção oposta ao centro da nossa galáxia.

M36, M37 e M38 foram identificados pela primeira vez em 1654 pelo astrônomo italiano João Batista Hodierna. Nascido na Sicília, Hodierna dividia seu tempo entre as atividades na igreja de Palma di Montechiaro e o estudo do Universo. Foi um dos primeiros astrônomos a observar o céu com um telescópio.

Podemos afirmar que Hodierna foi o precursor do trabalho de Messier. Mais de um século antes do francês, Hodierna elaborou um catálogo de cerca de 40 objetos de aparência nebulosa que poderiam ser confundidos com cometas, exatamente a mesma motivação que levou Messier a escrever seu catálogo.

Tesouros em Touro

Completando o hexágono temos Aldebaran, a estrela mais brilhante da Constelação do Touro. Seu nome quer dizer “a seguidora” em árabe, uma menção ao fato de que Aldebaran está ao lado do enxame das Plêiades e parece sempre seguir esse enxame de estrelas no céu.

Aldebaran se destaca das demais estrelas que vemos no céu pela sua coloração mais avermelhada, um indicativo de sua temperatura. Sua superfície é mais fria que a do Sol, cerca de 3600 kelvin.

Ao olharmos para Aldebaran estamos vendo o nosso próprio futuro. Ela se encontra num estágio evolutivo mais avançado que só será alcançado pelo nosso Sol daqui a milhares de milhões de anos.

O hidrogênio no núcleo de Aldebaran já foi todo consumido nas reações nucleares que fazem uma estrela brilhar. Ao acontecer isso, a estrela passou por uma transformação, aumentando muito o seu tamanho. Apesar de ter somente 50% mais massa que o Sol, o diâmetro de Aldebaran é 40 vezes maior, o equivalente ao tamanho da órbita do planeta Mercúrio.

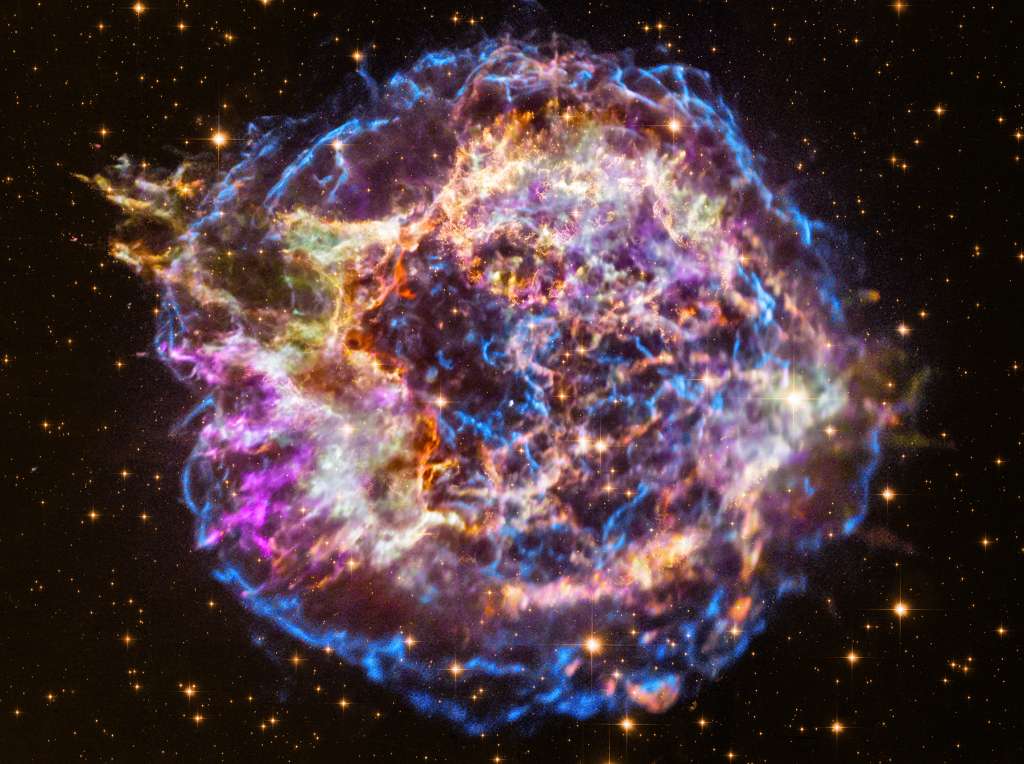

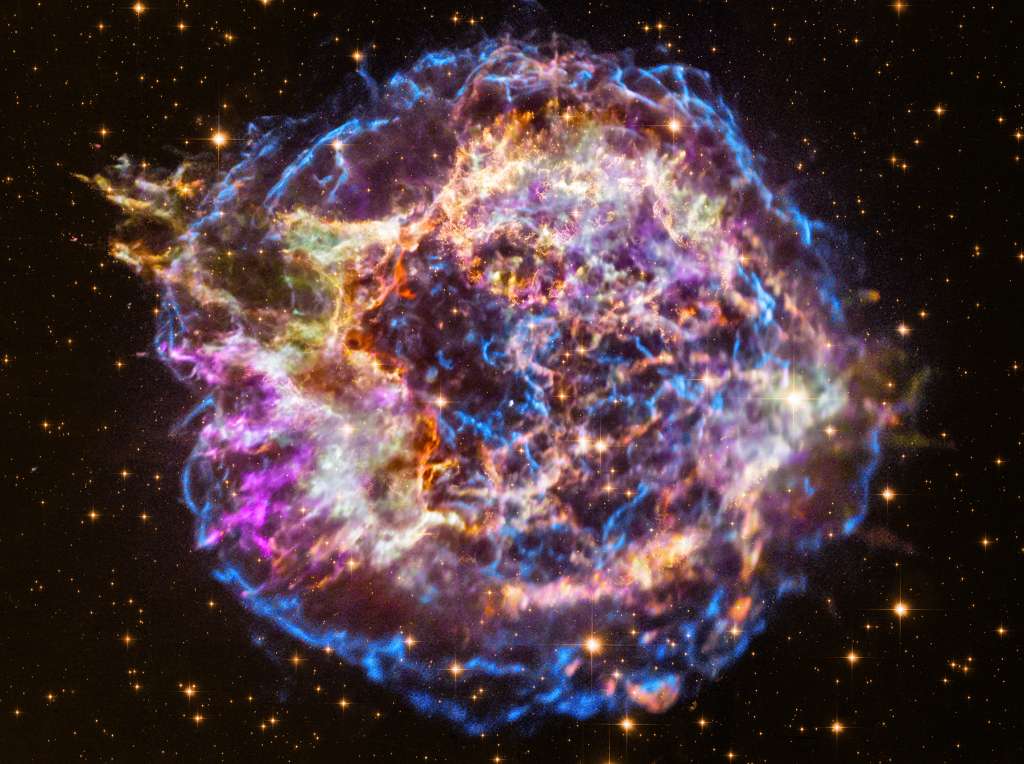

No Touro encontramos dois dos mais célebres objetos do catálogo de Messier, incluindo o primeiro de todos. M1 foi observado por Charles Messier em 1758 e o inspirou a compilar seu catálogo de objetos de aparência esfumaçada que poderiam ser confundidos com cometas. A hoje chamada Nebulosa do Caranguejo é o primeiro objeto do catálogo de Messier, e o único remanescente de supernova dessa lista.

Estrelas com mais de oito vezes a massa do Sol terminam sua evolução num evento extremo chamado supernova. Uma supernova é a explosão de uma estrela de alta massa, que ocorre quando a pressão interna da estrela não consegue mais suportar o seu próprio peso. As camadas externas da estrela colapsam e comprimem a matéria do núcleo estelar a densidades tão elevadas que superam a densidade de um núcleo atômico.

Como não é possível mais comprimir a matéria, o único movimento possível é para fora. As camadas externas são então expulsas violentamente para o espaço a incríveis velocidades. O processo libera uma imensa energia que por alguns dias brilha mais que uma galáxia inteira.

Foi exatamente isso que aconteceu em 4 de Julho de 1054, quando astrônomos na Ásia registraram a aparição de uma nova e brilhante estrela na região do Touro. Foi tão brilhante que pode ser vista a olho nu durante três semanas, mesmo durante o dia. O acontecimento também foi registrado por alguns povos indígenas americanos, mas curiosamente não há registros confirmados na Europa, que na época encontrava-se no auge da Idade Média.

Ao apontarmos um telescópio para a região dessa explosão, encontramos a nebulosa propriamente dita, composta pelos gases ejetados quando a estrela explodiu. No centro da nebulosa está o que restou da estrela que explodiu: uma estrela de nêutrons, um objeto extremamente denso e compacto. Ela concentra a massa de uma estrela como o Sol em uma esfera de apenas 30 km de diâmetro.

Estrelas de nêutrons como a que encontramos no centro dessa nebulosa possuem intensos campos magnéticos, e giram rapidamente, completando uma rotação em uma fração de segundo. São intensas fontes de ondas de rádio, que chegam à Terra em pulsos, como se fosse um farol de navegação. Por causa disso, recebem o nome de pulsares.

Hoje em dia os astrônomos conhecem cerca de 1100 pulsares, e o Pulsar do Caranguejo é um dos mais importantes, pois foi o primeiro a ser relacionado com uma explosão de supernova. Além das ondas de rádio, os pulsares também emitem intensamente em raios-X e raios gama, mas são pouco brilhantes na luz visível.

Se você tiver um telescópio, pode tentar localizar a nebulosa do caranguejo, próximo à estrela Zeta Tauri, na ponta do chifre do Touro. É preciso ter um telescópio de pelo menos 10 cm de abertura para conseguir enxergar a nebulosa, que aparecerá como uma tênue nuvem esbranquiçada.

O outro objeto de Messier em Touro são as Plêiades, objeto de número 45 do catálogo. É talvez o enxame estelar mais esplendoroso do céu. Suas estrelas mais brilhantes receberam o nome das sete irmãs da mitologia grega, filhas de Atlas e Pleione.

Várias outras culturas têm suas lendas sobre este enxame. Os indígenas brasileiros o chamam de Seixu. A aparição do Seixu ao amanhecer indica para esses povos o início da época de chuvas.

As estrelas das Plêiades estão distantes 440 anos luz da Terra e se formaram há 100 milhões de anos. Em fotografias de longa exposição é possível observar uma nebulosidade entre suas estrelas.

Durante muito tempo acreditou-se que esse material era remanescente do gás que deu origem a elas, mas a explicação mais aceita atualmente é de que se trata apenas de uma região mais rica em gás e poeira que está sendo atravessada pelo enxame.

No total, as Plêiades têm cerca de mil estrelas, que permanecerão juntas por ainda 250 milhões de anos antes de se dispersarem pela galáxia.

O conjunto de estrelas pode ser facilmente avistado a olho nu até mesmo de localidades urbanas, entre as constelações de Touro e Áries. Por ocuparem uma vasta área no céu, as Plêiades são melhor observadas com binóculos ou instrumentos de pouco aumento. Usar uma magnificação elevada irá mostrar apenas alguns membros do enxame.

O que ver no céu em março

5/3: Encontro ao amanhecer

Os planetas Mercúrio e Júpiter fazem uma conjunção próxima na manhã desse dia, com Saturno participando à distância. Olhe para a direção do nascente 1 hora antes do sol nascer.

10/3: A Lua e três planetas

A Lua quase nova junta-se ao trio formado por Mercúrio, Júpiter e Saturno no horizonte leste, marcando um belo início de dia.

20/3: Bem vindo, Sol

O Sol volta ao hemisfério norte celeste às 9:37 (hora de Lisboa), e só cruzará o equador celeste novamente em 22 de setembro de 2021. É o início da primavera no hemisfério norte, e do outono no hemisfério sul.

Na próxima semana …

A última parte do Tema do Mês fala das constelações mais ao norte no céu em posição privilegiada para observações. Até lá!

O Céu de Inverno – Parte 4

Atrações do Norte

Concluindo a série de artigos sobre o Céu do Inverno, vamos conhecer algumas constelações próximas ao pólo norte celeste, e que nesta época do ano estão visíveis no céu durante o início da noite.

A Rainha e o Rei

Nossa primeira parada é em Cassiopeia. Na mitologia grega, Cassiopeia era uma rainha muito vaidosa, casada com o rei Cefeu, e mãe da princesa Andrômeda. A lenda grega diz que Cassiopeia enraiveceu o deus Poseidon após afirmar que sua filha era muito mais bonita que as ninfas Nereidas.

Como castigo, Poseidon condenou Cassiopeia a girar em torno do pólo norte celeste por toda eternidade, presa em seu trono. Durante metade do tempo Cassiopeia fica pendurada de cabeça para baixo, segurando-se para não cair.

Cassiopeia é uma das 48 constelações originais listadas pelo astrônomo grego Claudio Ptolomeu na sua famosa obra Almagesto. Sua característica principal é a figura formada pelas suas 5 estrelas mais brilhantes. Dependendo da época do ano, esse desenho lembra as letras W ou M.

Cassiopeia foi o palco de um evento marcante na história da Astronomia. Foi nessa constelação que, em 1572, o célebre astrônomo dinamarquês Tycho Brahe observou uma estrela que não estava nas cartas celestes. Assombrado com a aparição, que permaneceu visível no céu por um ano e meio antes de desaparecer, ele inventou o termo “estrela nova”.

A estrela nova de Tycho foi na verdade uma explosão de supernova, o final catastrófico de uma estrela com massa muito maior que a do Sol. Hoje, tudo o que resta da explosão é uma nebulosa com intensa emissão de ondas de rádio e raios-X.

Esta não foi a única supernova registrada na constelação. Outra supernova aconteceu em Cassiopeia em 1660, e também é uma intensa fonte de ondas de rádio.

Em Cassiopeia encontramos dois enxames estelares do catálogo de Messier. O mais famoso é M103, um dos últimos a ser adicionado ao catálogo em 1781. Messier utilizou observações do seu colaborador Perre Mechain, que contribuiu com a descoberta de pelo menos 31 dos 110 objetos do catálogo.

Distante 9 mil anos luz da Terra, M103 é um dos enxames estelares abertos mais distantes conhecidos. É bastante jovem, tendo se formado há apenas 25 milhões de anos. Nele foram identificados quase 200 membros, sendo que os mais luminosos são gigantes azuis e vermelhas.

No mesmo campo de M103 encontramos a brilhante estrela dupla Struve 131, porém ela não está associada ao aglomerado. M103 é considerado um objeto de fácil localização no céu, podendo ser observado até mesmo com binóculos. Está localizado próximo de Rucbah, uma das estrelas que formam a figura da letra M .

Completando a lista de objetos de Messier em Cassiopeia temos M52, outro aglomerado estelar aberto situado num rico campo estelar. Contém cerca de 200 estrelas formadas 35 milhões de anos atrás.

Na mesma região do céu está outra constelação associada a essa lenda da mitologia grega: Cefeu, o rei da Etiópia e marido de Cassiopeia.

A estrela mais famosa dessa constelação é Delta Cephei, protótipo de uma classe muito especial de estrelas variáveis, que têm importância fundamental no desenvolvimento da astronomia moderna. Seu brilho varia de uma maneira extremamente regular, aumentando e diminuindo cerca de 50% em pouco mais de 5 dias.

Esse comportamento, percebido pela primeira vez em 1784 pelo astrônomo inglês John Goodricke, logo foi observado em outras estrelas. Chamamos as estrelas cujo brilho varia dessa maneira de variáveis cefeidas.

As cefeidas são importantes na astronomia porque o período da variação de brilho está diretamente ligado à luminosidade total da estrela. Quanto mais brilhante a estrela, mais tempo leva para a variação de brilho completar um ciclo completo.

Essa relação entre período e luminosidade foi descoberta em 1908 pela astrônoma americana Henrieta Leavitt, e é até hoje um dos principais indicadores de distâncias no Universo. Foi a partir dela que em 1929 o astrônomo Edwin Hubble determinou que o Universo está em expansão.

O Herói

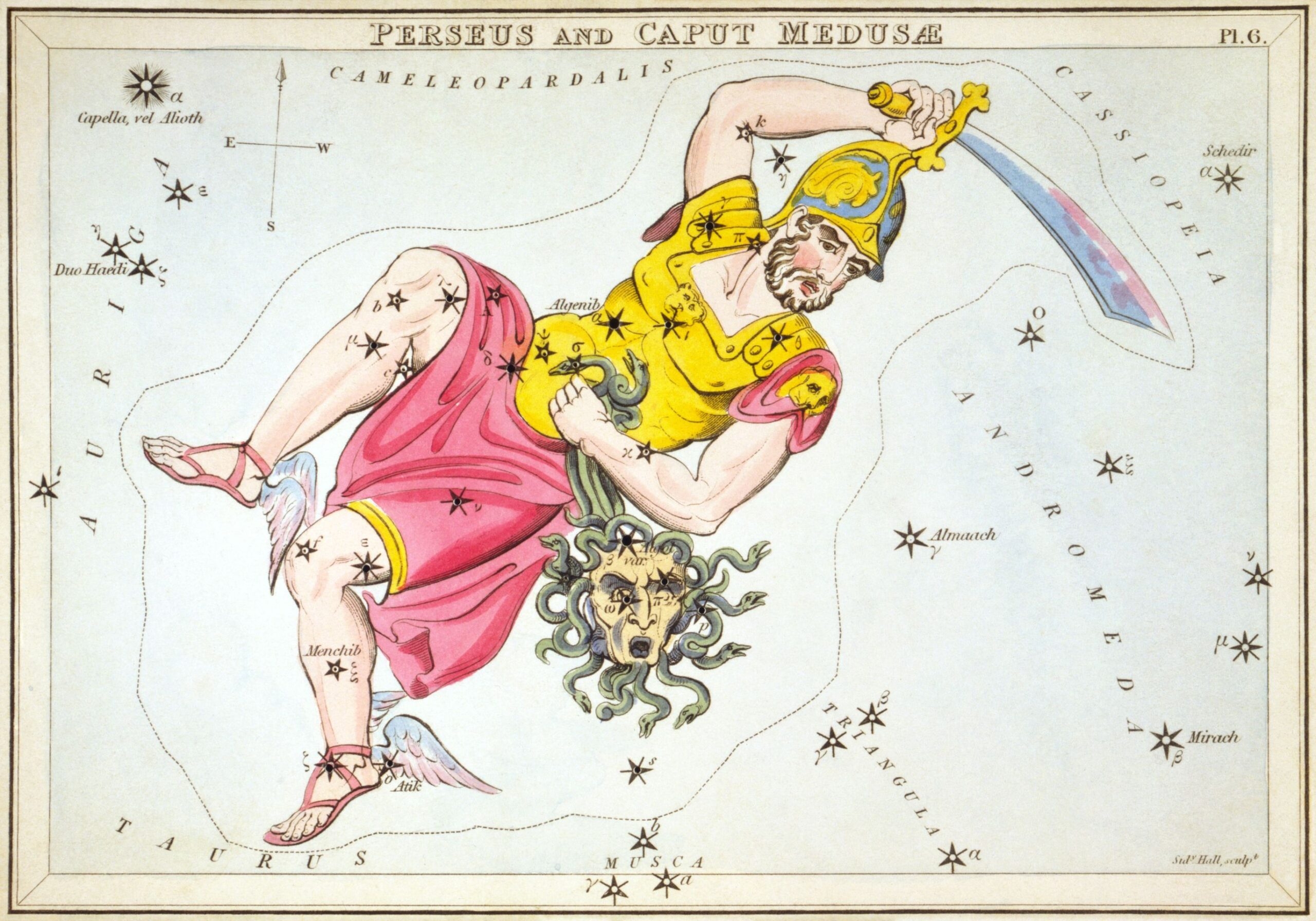

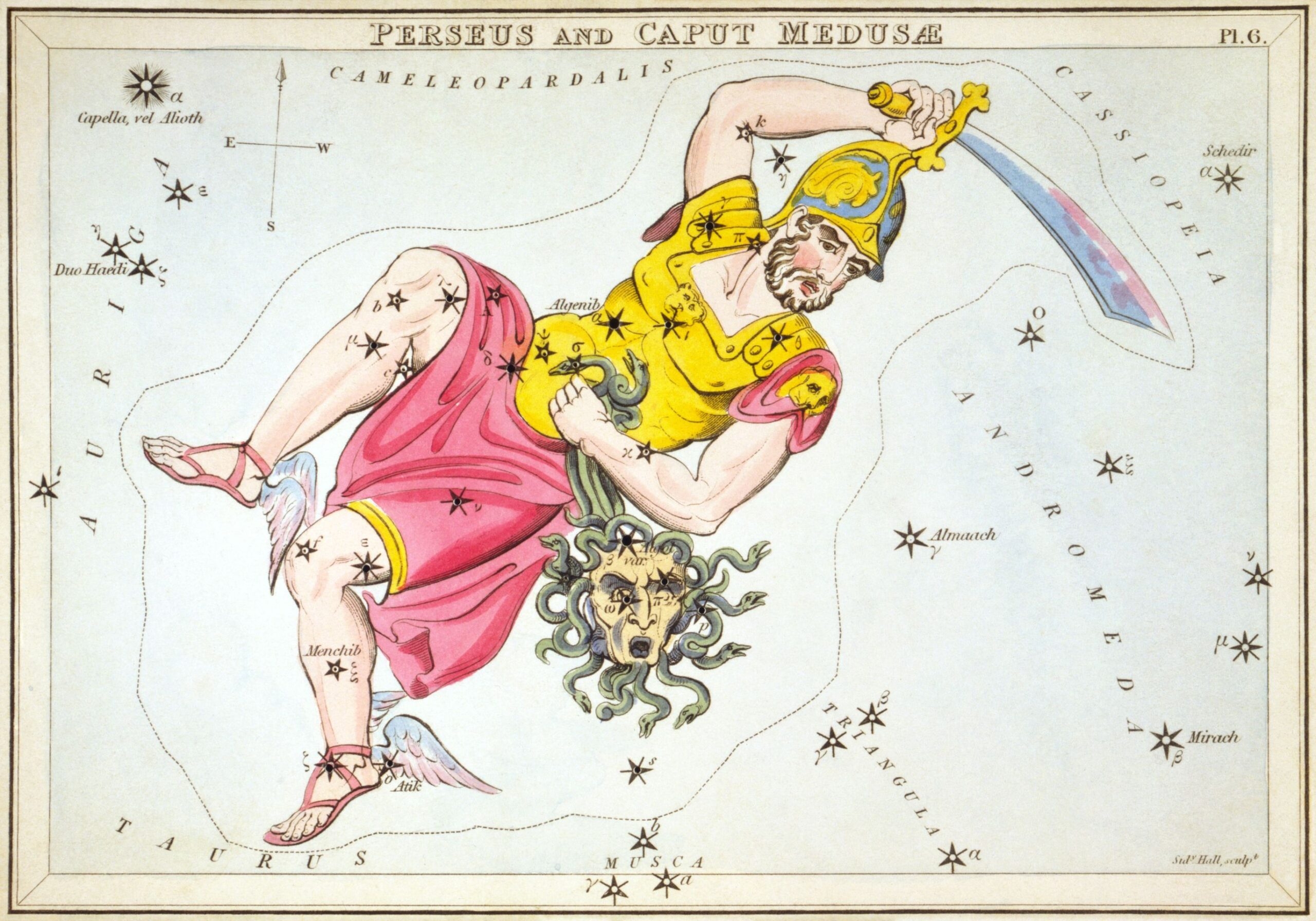

Vizinha a Cassiopeia está a constelação de Perseu, que representa um dos mais famosos heróis da mitologia grega.

Perseu é protagonista de inúmeras aventuras. A mais famosa envolve sua batalha com Medusa, uma das três irmãs Gorgons, seres horrendos que petrificavam a todos com seu olhar.

Perseu havia sido incumbido de trazer a cabeça da Medusa pelo Rei Polidetes. Para este temível combate, Perseu levou um equipamento especial. A deusa Atena deu a ele um escudo de bronze, tão polido que podia servir como espelho. Hermes lhe deu uma espada de diamantes e sapatos alados. E Hades presenteou-o com um capacete que o tornava invisível.

Ao chegar ao Monte Atlas, onde Medusa se escondia, Perseu seguiu a trilha de homens e animais petrificados, protegido por seu capacete de invisibilidade. Chegando ao esconderijo da Medusa, esperou até que ela dormisse. Para não virar pedra, Perseu se aproximou dela olhando apenas para seu reflexo em seu escudo, e decapitou-a. Para sua surpresa, nesse instante surgiu do ventre da Medusa o cavalo alado Pégaso, no qual Perseu montou e escapou.

No caminho de volta, Perseu viu a princesa Andrômeda acorrentada a um rochedo, prestes a ser devorada pelo monstro marinho Cetus. Perseu mostrou a cabeça decepada da Medusa ao monstro, transformando-o em pedra. Assim salvou a donzela e casou-se com ela.

No céu, a constelação de Perseu não possui nenhuma estrela muito brilhante. A mais famosa é Algol, uma estrela variável. A cada 3 dias, o brilho de Algol começa a diminuir. Depois de 4 horas, está apenas com metade do brilho do que tinha antes. Permanece assim apagada por cerca de 20 minutos, e depois volta ao seu brilho normal.

Por causa deste estranho comportamento, ela foi apelidada de Estrela do Demônio. Foi somente em 1728 que o astrônomo inglês John Goodricke encontrou a explicação para os apagões de Algol. Ela é uma estrela binária, onde uma das estrelas é uma pequena e brilhante, e a outra é maior e menos brilhante. Quando a estrela maior passa na frente da mais brilhante, acontece um eclipse, e o brilho do sistema diminui. Este tipo de sistema é chamado de binária eclipsante.

Perseu é atravessada pelo plano da nossa galáxia, a Via Láctea, e conta com um considerável número de objetos de céu profundo. Os mais conhecidos são h e chi Persei, também chamados de Enxame Duplo.

Esse enxame binário contém milhares de estrelas formadas há 13 milhões de anos. Apesar de estarem a mais de 7 mil anos luz da Terra, podem ser facilmente observados a olho nu em locais de céu escuro. Ao telescópio, são uma das visões mais inspiradoras que a Astronomia pode proporcionar.

Por algum motivo desconhecido, o Enxame Duplo não está representado no popular catálogo do francês Charles Messier. O único enxame estelar de Perseu presente nessa lista é M34, situado próximo à divisa com Andrômeda.

M34 é um dos objetos de Messier mais próximos da Terra. Está a 1500 anos luz daqui, e pode ser facilmente observado com binóculos. Formado há 200 milhões de anos, já está em um estágio intermediário de evolução, tendo perdido seus membros de maior massa. Pelo menos 19 anãs brancas já foram identificadas em M34.

Para localizar este enxame, trace uma linha entre as estrelas Algol e Almach, em Andrômeda. M34 estará bem na metade dessa linha. Um bom exercício para que está aprendendo a navegar pelo cosmos.

O outro objeto de Messier em Perseu é a nebulosa planetária M76. Messier adicionou o objeto em sua lista em 1780, mas sua estrutura peculiar só foi identificada em 1918 pelo americano Heber Curtis.

M76 é uma nebulosa planetária de tipo bipolar, com cerca de 1,2 anos-luz de extensão, e distante 2500 anos luz da Terra. Sua estrutura é semelhante à de outro objeto de Messier, M27, na constelação da Raposa. Por causa dessa semelhança, M76 é também chamada de Pequena Nebulosa do Haltere.

Sua estrela central é uma anã branca com temperatura superficial de quase 70 mil graus. A luz ultravioleta que emana da estrela excita os átomos da nebulosa ao redor, fazendo-a brilhar em cores características. Em fotografias de longa exposição é possível detectar um halo mais extenso ao redor do objeto, expandindo-se a 40 km/s.

Localizar M76 no céu é um desafio até para astrônomos experientes. É um objeto pequeno e de baixo brilho, sendo necessário um telescópio amador de porte intermediário e um céu bem escuro.

Partindo da estrela 51 Andromedae, siga na direção norte até a estrela fraca Phi Persei. M76 está a cerca de um grau desta estrela.

A constelação de Perseu também é muito conhecida por causa de uma das mais famosas chuvas de meteoros, as Perseidas, que acontece em agosto. No Céu do Verão falamos sobre essa chuva de meteoros.

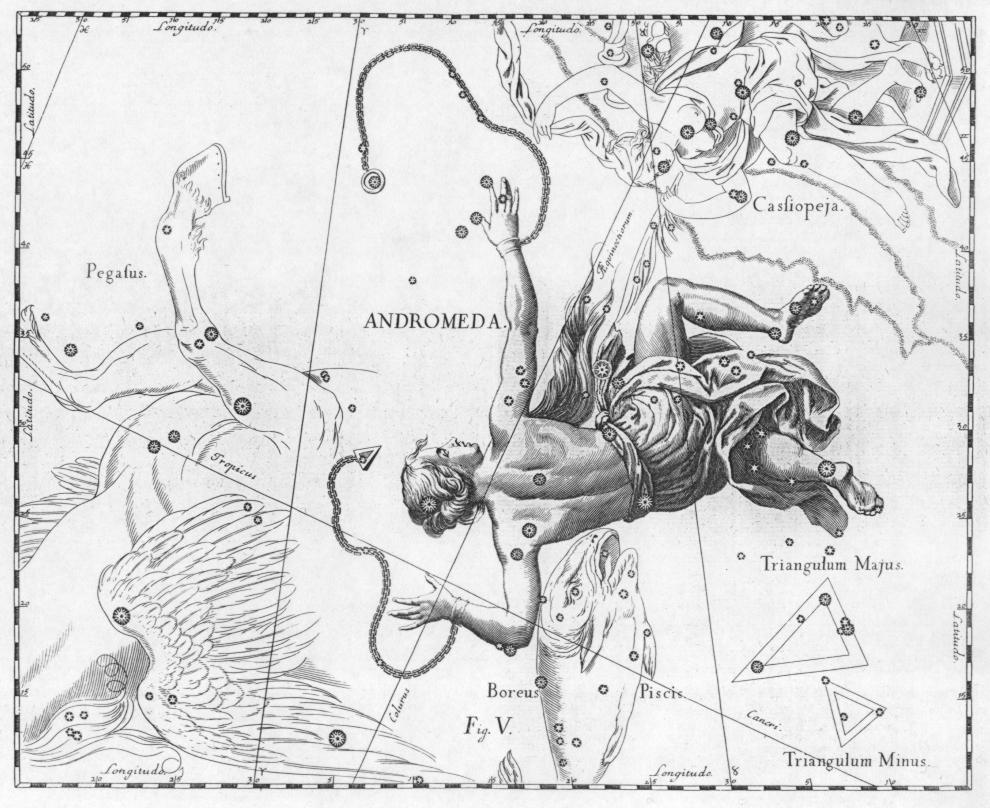

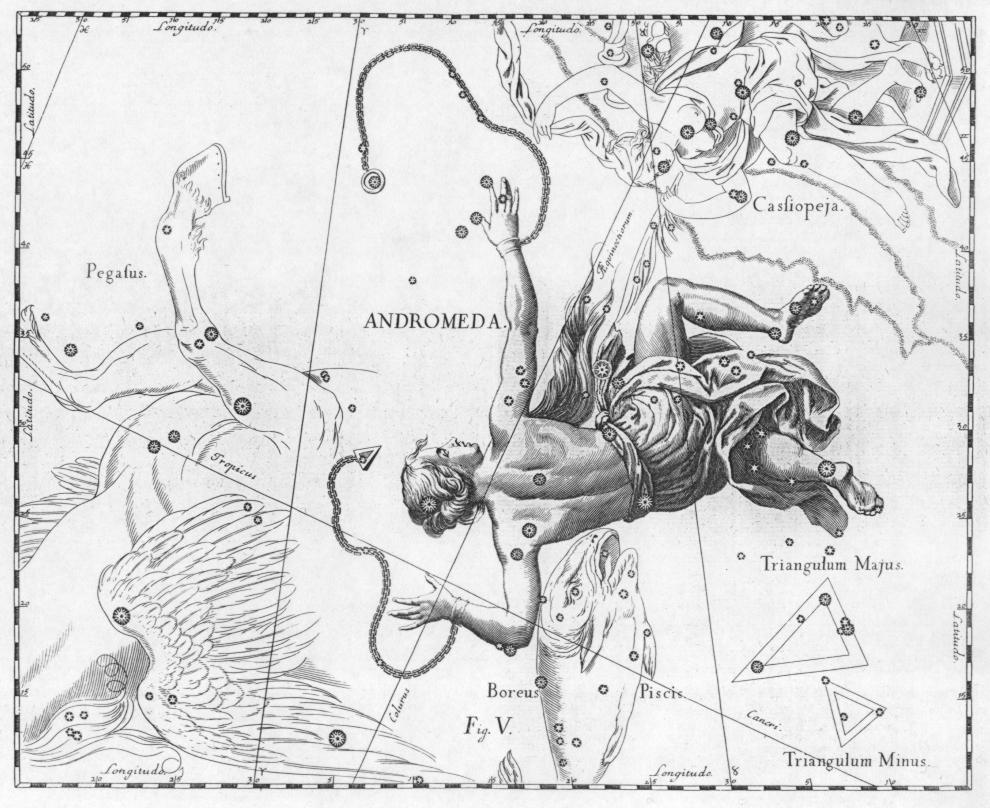

A Princesa

Completando esse passeio pelas constelações boreais temos Andrômeda. Filha de Cassiopéia e Cefeu, o rei da Etiópia, Andrômeda era uma jovem de extrema beleza, mais bela até que as Nereidas, as Ninfas do Mar, que eram filhas de Poseidon.

Invejosas com a beleza de Andrômeda, as Nereidas pediram a seu pai que enviasse o monstro marinho Cetus para dizimar a costa da Etiópia, (uma região de Israel, não o país africano). Temendo pelo seu reino, Cefeu consultou um oráculo, que lhe disse que a única maneira de impedir a destruição seria sacrificar sua filha ao monstro.

E assim Cefeu o fez, acorrentando a jovem Andrômeda a pedras no litoral. O resto da história você já conhece – Perseu transformou o monstro em pedra, e salvou a bela donzela.

Assim como na lenda, no céu a constelação de Andrômeda é representada por uma jovem acorrentada a pedras. É nela que encontramos um dos objetos celestes mais apreciados pelos astrônomos: M31, a Galáxia Espiral de Andrômeda.

Essa imensa galáxia, maior até que a nossa Via Láctea, pode ser vista a olho nu, apesar de estar a mais de 2 milhões e meio de anos-luz de distância. É o objeto mais distante que pode ser observado pela visão humana sem o auxílio de instrumentos ópticos.

Durante séculos, a galáxia foi chamada de Grande Nebulosa de Andrômeda, pois não se conhecia a sua natureza extra-galáctica. Acreditava-se então que ela era apenas mais uma nuvem de gás pertencente à nossa galáxia. Somente em 1924 que o astrônomo americano Edwin Hubble conseguiu estabelecer uma medida precisa da distância da galáxia – revolucionando a Astronomia e multiplicando o tamanho do Universo conhecido.

Durante o inverno podemos observar esta galáxia no início da noite. Como em toda observação astronômica, é necessário estar em um local de céu bastante escuro, afastado das luzes das cidades. A olho nu, a galáxia tem aparência de uma nuvem tênue, mas se observada com um binóculo revela mais detalhes.

Ao redor da grande espiral encontramos 14 galáxias menores. As duas galáxias satélites mais brilhantes fazem parte do catálogo de Messier. M32 é a mais brilhante delas. Classificada como uma galáxia elíptica anã, possui uma grande quantidade de estrelas compactada em um volume pequeno, e com um buraco negro supermassivo em seu centro. Os astrônomos acreditam que M32 era uma galáxia comum que teve a maior parte de suas estrelas e gás roubada pela gigante M31 durante uma passagem próxima.

M110 também é uma galáxia anã, mas com densidade estelar muito inferior à de M32. É o último objeto da lista de Messier, mas não consta da relação original. Recebeu esse número somente em 1966, por sugestão do astrônomo Kenneth Jones, baseado numa anotação de Messier na obra Conhecimento do Tempo publicada em 1801.

E assim chegamos ao final deste Tema do Mês. Espero que os textos tenham sido inspiradores! Até uma próxima oportunidade e céus limpos a todos!

The Winter Sky

The long, cold nights of winter are not very inviting to observe the sky. However, anyone willing to challenge the thermal discomfort is rewarded by magnificent views of the season’s bright constellations.

The main celestial attractions in the coming months include beautiful planetary conjunctions and meteor showers. Above all, it is the ideal time to explore the bright nebulae on Orion and to contemplate the largest galaxy in our cosmic neighborhood: M31, the Great Andromeda Spiral.

In this month’s topic, we will see the main astronomical phenomena of the coming months, their characteristic constellations, and celestial objects of interest. Get a good coat, face the cold, and look at the sky!

Author: Gustavo Rojas

Gustavo has a Ph.D. in Astronomy (University of São Paulo, 2008) and began his professional career at the Federal University of São Carlos, Brazil. He has been working for more than 10 years with science outreach and education and acted as the Brazilian representative for ESO Outreach and Science Network from 2011 to 2018. A member of the International Astronomical Union, Brazilian Astronomical Society, and Portuguese Astronomy Society, Gustavo is part of the organizing committee of the Brazilian Astronomy and Astronautics Olympiad, one of the largest science olympiads in the world. Since 2012, Gustavo participates as Team Leader in the International Olympiad on Astronomy and Astrophysics (IOAA) for Brazil (2012-2018) and Portugal (2019). Currently, he works as project coordinator at NUCLIO – Núcleo Interactivo de Astronomia, Portugal.

⬇︎ Click below to read each part of this theme

The Winter Sky – Part 1

When is the winter, after all?

In astronomy, the beginning of winter is marked by the December solstice, when the Sun reaches the southernmost position in the celestial sphere. On that date, we have the shortest day of the year in the northern hemisphere. However, the lowest temperatures are usually recorded a month or two later. In 2020, the solstice took place on December 21st at 10:02 am (Portugal time).

Typical constellations

In the northern hemisphere, the winter sky is marked by the Winter Hexagon, formed by the bright stars Rigel, Aldebaran, Capella, Pollux, Procyon, and Sirius. These stars indicate some of the main constellations of the season: Orion (The Hunter), Taurus (The Bull), Auriga (The Charioteer), Gemini (The Twins), Canis Minor (The Lesser Dog), and Canis Major (The Greater Dog).

Among them, Orion stands out as one of the best-known constellations in the heavens. Its figure is easily recognizable by the large quadrilateral with vertices in Bellatrix, Betelgeuse, Rigel, and Saiph. At the center, the unmistakable trio of Alnitak, Alnilam, and Mintaka form the Orion Belt. There are several interesting myths about Orion in different cultures worldwide.

The best-known legend comes from the Greco-Roman culture. In one version of the Greek legend, Orion was a giant hunter, son of Poseidon with a mortal.

Orion met Artemis, hunting goddess, sister of Apollo, the god of reason. Artemis and Orion became friends and later fell in love, making Apollo jealous. To kill Orion, Apollo sent a giant scorpion to sting him.

Trying to escape from the scorpion, Orion entered the sea, keeping only his head out. Realizing this, Apollo challenged Artemis to hit a dark spot in the sea with an arrow, which was actually Orion’s head. Artemis hit the target, killing Orion. Realizing what she had done, Artemis asked Zeus to place Orion in heaven.

Zeus granted the request, meanwhile also placing the scorpion in the sky. That would be the reason why Orion and Scorpio never appear together in the sky: Orion is always on the run from the scorpion.

For the indigenous peoples from Brazil, the stars of Orion are part of a larger constellation, “Homem Velho” (The Old Man), which also includes part of Taurus. The Guarani legend says that the Old Man married a much younger woman, who became interested in his young brother-in-law and killed his husband by cutting his leg at the level of his right knee.

The gods took pity on the man and turned him into a constellation, with Betelgeuse indicating the point where his leg was cut. The Old Man’s head is formed by stars of Taurus: the Hyades cluster ist he face, with a plume above where the Pleiades cluster is located.

The main attraction in the constellation is the Great Orion Nebula, indicated by the number 42 in the Messier catalog. Distant 1340 light-years from Earth, M42 is known since antiquity. It can be seen with the naked eye even in urban areas, as a small fuzzy spot in the sword region of this mythological figure.

With binoculars or a small telescope, the gaseous nature of the nebula is more evident. Magnifications as low as 30 times can already separate the brightest stars from the Trapezium cluster in the heart of the nebula.

The Trapezium is named after the geometric figure formed by its four brightest stars. Each of them is a blue supergiant with dozens of times the mass of our sun. The ultraviolet light of these stars excites the gas in the nebula, making it shine brightly.

In total, it is estimated that the nebula contains material to give rise to hundreds of thousands of stars like the Sun. This process, however, is very slow compared to the human time scale. A star like the Sun, for example, takes several million years to form. It is believed that M42 will still shine for at least another million years.

Due to its proximity and size, the Orion Nebula is the star-forming region most studied by astronomers. There, the initial stages of star formation have been observed, such as proplyds, Herbig-Haro objects, and protoplanetary disks.

Messier catalog contains another object very close to M42, which received the next number in the catalog. M43 is also known as the De Mairan Nebula, in honor of its discoverer, fellow Frenchman Jean Jacques De Mairan.

Strictly speaking, M43 is part of the Great Orion Nebula. However, it appears to be an independent object thanks to the presence of a thick lane of dust that visually separates the two nebulae. Therefore, it shares the same general characteristics as its most famous sister.

M43 is also a region of intense star formation. The nebula shines thanks to the ultraviolet radiation emitted by its most massive stars, in particular the NU Orionis triple system.

M42 and M43 are part of an even larger structure known as the Great Molecular Complex of Orion. This enormous accumulation of gas and dust spans over a thousand light-years and encompasses a large number of well-known nebulae.

Among the objects that are part of this complex stands out the remarkable Barnard 33, better known as the Horsehead Nebula. The nickname comes from the curious silhouette created by dark dust in front of the bright magenta gas cloud. This color comes from hydrogen gas excited by the ultraviolet radiation from hot star Sigma Orionis.

The Horsehead Nebula is one of the most iconic images in astronomy and has been featured in many science fiction works, including The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. In the novel, the nebula harbors planet Magrathe, home of the civilization that built Earth.

Observing the Horsehead requires very dark skies and a telescope with at least 20 cm aperture. Special nebulae filters can also help. With this gear, look for it next to the star Alnitak, the easternmost of Orion’s Belt.

Completing the list of Messier objects in Orion is M78. Like its neighbors M42 and M43, M78 is also part of the huge structure known as the Orion Molecular Complex, a gigantic molecular cloud over a thousand light-years in length.

M78 is the brightest object in the group, which also includes the nebulae NGC 2064, NGC 2067, and NGC 2071. It can be located with small telescopes, in the region between the red giant Betelgeuse and Alnitak.

The M78 region contains many newborn stars, including dozens of T-Tauri variables, which still have dusty disks where planets are forming. Long exposure photographs reveal an intricate variety of regions of emission, reflection, and absorption, manifestations of gas and dust associated with the phenomenon of star formation.

Another curious object associated with M78 is NGC 2024, better known by its popular name, Flame Nebula. This nebula is also very close to the star Alnitak.

Like its neighbor Horsehead Nebula, the Flame Nebula is an astrophotographer’s favorite, but difficult to spot with telescopes. Only large instrument apertures will allow you to appreciate all the splendor of this region of star formation.

What to see in the sky in January

2/1: Closer to the Sun

Our annual journey around the Sun does not take a circular path. The Earth’s orbit is slightly oval, and as a result, the Earth-Sun distance varies slightly throughout the year. The maximum approach, called perihelion, takes place in January and measures approximately 147.1. million km. In July, it’s time for us to be a few million kilometers farther from our star. This point in orbit is known as an aphelion, where the distance to the Sun reaches 152.1 million kilometers.

Although 4 million kilometers is an extremely large number (more than 10 times the distance to the Moon), we cannot see any variation in the apparent size of the Sun. Only in photographic records can this difference of about 3.5% be noticed.

3/1: Quadrantid meteors

The first meteor shower of the year takes its name from an extinct constellation: Quadrans Muralis, proposed by Frenchman Jerôme Lalande in the 17th century. The constellation symbolized a great instrument used to measure angles in the sky, but it was never adopted on modern celestial maps.

Despite this, Lalande’s suggestion is still used today to designate the Quadrantid meteor shower, whose radiant is located in the area currently occupied by Bootes and Draco. This rain was first observed in the mid-1830s in Europe and North America.

To observe the Quadrantids, look north before dawn, towards the star Arcturus. It is not a spectacular shower, but in ideal conditions, up to 30 meteors per hour can be seen.

24/1: Mercury in Maximum Elongation

Mercury reaches its greatest distance from the Sun, shining with apparent magnitude -0.7. It can be seen on the West horizon after sunset, on the border between Aquarius and Capricorn.

Next week …

The Theme of the Month continues with more curiosities of the winter constellations, and observation tips for February. See you later!

The Winter Sky – Part 2

Celestial Dogs

Surrounding Orion, we find two other typical winter constellations, which symbolize the dogs of the giant hunter.

The largest and brightest is Canis Majoris (the Greater Dog), with Sirius, the brightest star in the sky, marking the dog’s head Two other very bright stars outline the animal’s shape. Mirzam is located at one of the dog’s paws. Its Arab name means “the announcer”, as the star appears in the sky just before Sirius.

On the other side, at the dog’s back, is Wezen, also an Arabic name meaning “heavy”. Interestingly, Wezen is indeed a very massive star, 10 times more massive than our Sun.

The other dog, Canis Minoris (the Lesser Dog), is much less impressive, with a single bright star: Procyon. It is a nearby star only 11 light-years away. As the 8th brightest star in the sky, it forms a triangle with Sirius and Betelgeuse, Orion’s red giant.

Due to its brightness, Sirius has a prominent place in many cultures around the world. There are more than 50 different names for this special star.

As one of the closest stars to the Sun, Sirius is one of the best-studied objects in the sky. In the 19th century, the famous American telescope maker Alvan Clark discovered Sirius’ weak companion star, inspired by calculations made by German astronomer Friedrich Bessel.

This dim object is Sirius B, a white dwarf star. It has almost the same mass as the Sun but compacted to a volume similar to that of Earth.

This impressive density is the result of the stellar evolution of a star five times the mass of the Sun, which consumed all the hydrogen in its core in just over 100 million years. What remained is a carbon and oxygen dense core, with surface temperatures reaching 25,000 degrees.

Sirius B is part of a controversy involving a primitive African ethnic group. The Dogons, people that inhabit the Bandiagara plateau in Mali, have an interesting cosmology involving spirits called Nommo.

In the 1930s, two French anthropologists who lived with the Dogons published impressive accounts. According to them, the Nommo spirits were inhabitants of the Sirius system, and passed on to the Dogons advanced astronomy knowledge, including the size, density, and orbital period of Sirius B.

The story gained notoriety in the 1970s when author Robert Temple wrote the book “Sirius Mystery”. In this work, he tries to associate the account of French anthropologists with an alleged contact of the Dogons with extraterrestrials, who would have passed on information about the existence of the white dwarf.

Although fantastic, this hypothesis was not well received by astronomers and anthropologists, who found no convincing evidence. As Carl Sagan said, extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.

The most likely explanation is that the Dogon people acquired this information from European missionaries who visited Mali in the late 19th century and were quickly incorporated into their oral tradition. Is that the answer to the Sirius Mystery? We may never know the answer …

Canis Majoris also harbors one of the most luminous stars ever discovered, which for a long time held the record for the largest known star.

VY Canis Majoris is a red hypergiant, 4 thousand light-years from Earth. It is associated with a star-forming region next to star cluster NGC 2362. It is a very young star, formed a few million years ago but which is already at an advanced evolutionary stage.

Born as a blue hypergiant of at least 15 solar masses, it quickly consumed the hydrogen in its core. As a consequence, it underwent a great expansion, cooling its outer layers.

VY Canis Majoris emits almost 300 thousand times more energy than the Sun. It is estimated that its surface temperature is approximately 3500 degrees and its diameter is 1420 times larger than our Sun’s. If we replaced the Sun with VY Canis Majoris it would swallow all the planets up to Jupiter! Its surface would span almost 7 astronomical units, equivalent to 1 billion kilometers!

Despite its impressive size, it is no longer the largest known star, having been surpassed by other hypergiants such as RW Cephei and UY Scuti, the current record holder with 1700 sun diameters.

You can observe VY Canis Majoris with an amateur telescope. It is a faint 8th magnitude star and forms a triangle with Wezen and Aludra. A nice observing challenge for the start of the year.

Interestingly, in Canis Majoris, we find only one deep-sky object present in Messier’s catalog. On the other hand, it is a spectacular open cluster.

Messier 41 has been known to astronomers for a long time. It is bright enough to be seen with the naked eye in very dark skies. Its first appearance in an astronomical catalog was in 1654, in the list compiled by the Italian Giovanni Batista Hodierna. The Englishman John Flamsteed also registered the cluster on his British Catalog in 1702.

M41 is a fairly young cluster, formed 190 million years ago. It contains about 100 stars gathered in a diameter of 25 light-years, including some red giants and white dwarfs. It is approximately the same distance from us as another cluster called Collinder 121. Some astronomers suspect that the two clusters may have a common origin, but this is a hypothesis that is still being studied.

M41 is an easy target to locate, forming a triangle with Sirius and the star Nu Canis Majoris. It can be easily seen with binoculars.

What to see in the sky in February

18/2 Moon Meets Mars

During the first half of the night, the crescent moon is positioned just below the red planet, towards the southwest.

24/2 Hive Moon

The almost full moon passes close to the Beehive Cluster (Messier 44), in Cancer. Use binoculars to locate the cluster below the Moon and observe dozens of stars.

Next week …

The Theme of the Month continues its tour of the typical winter constellations, and gives more observing tips for March. See you soon!

The Winter Sky – Part 3

Closing the Hexagon

The main feature of the winter sky is the set of bright stars forming the Winter Hexagon. During the past weeks, I wrote about three constellations whose stars make up the asterism: Orion (Rigel), Canis Major (Sirius), and Canis Minor (Procyon). Let’s visit now the three remaining constellations.

North of Procyon, the brightest star in Canis Minor, is the first constellation of interest: Gemini, the Twins, with the pair of bright stars Castor and Pollux.

Heavenly Twins

This stellar duo of similar brightness makes Gemini one of the easiest zodiacal constellations to identify. The earliest star catalogs, such as the one by Ptolemy in the 4th century, marked both stars with the same brightness. When Johann Bayer attributed the Greek letters to the stars in 1603, Castor was still the brightest one. It was only in the 19th century that Pollux became recognized as the most brilliant in the constellation. We don’t know the reasons for this discrepancy.

The stars have different colors. Pollux has a slight orange hue. Castor, on the other hand, is white and, when seen through the telescope, reveals itself as a double star. In fact, Castor was the first stellar system identified as binary. William Herschel found that they orbit around the system center of mass, with a period of 420 years.

Later studies have shown that each of these components is also a double star, too close to be resolved with telescopes, but detectable by spectroscopy. There is also a distant third pair of stars belonging to the system, known as YY Geminorum. This makes Castor a rare sextuple star system.

In Gemini, we find only one Messier object. M35 was discovered independently by astronomers John Bevis and Philip de Cheseaux in the middle of the 18th century and later incorporated by Charles Messier in his famous catalog.

This cluster is 2800 light-years away from Earth and is reasonably young, astronomically speaking. Formed 150 million years ago, M35 still retains some of the gas and dust remaining from its parent nebula, as evidenced by the scattered blue light of its brightest stars.

The cluster is quite extensive, and best seen with low-magnification instruments. Even a small telescope can reveal almost a hundred stars. In total, M35 has about 2500 members concentrated in a diameter of 30 light-years.

In the same region of the sky is another cluster, NGC 2158. Despite the apparent proximity, the two clusters have no connection between them. NGC 2158 is four times more distant and is much older than M35.

Nearly 2 billion years old, NGC 2158 was initially classified as a globular cluster, but today we know that it is a very evolved open cluster. Its advanced age is indicated by the absence of blue stars, which evolve more quickly and explode after a few hundred million years. Old swarms like NGC 2158 present a population almost entirely composed of reddish stars.

To locate this curious pair in the sky, point your binoculars or telescope at the star Eta Geminorum. This star forms the left foot of one of the twins in the constellation, whose head is marked by Castor. The cluster will appear in the vicinity of Ets Geminorum.

The Chariot and the Goat

North of Gemini is the constellation of Auriga, the Charioteer. Its brightest star, Capella, is one of the vertices of the hexagon. Capella is the sixth brightest star in the sky and the first-magnitude star nearest to the north celestial pole. It has been associated with a goat since Mesopotamian times. In fact, the name Capella means “little goat” in Latin, a reference to the goat Amalthea, who suckled Zeus.

Auriga represents the driver of a small chariot, accompanied by goats. In addition to Capella, stars Zeta and Eta Aurigae represent these animals. This pair is known as “Haedi”, which means “goats” in Latin.

Capella is actually a quadruple star system, composed of two yellow giants and two red dwarfs. The yellow giants each have 3 times the mass of the Sun, and together they shine 140 times more than our star.

The Capella system is quite close to Earth by astronomical standards, just 40 light-years away. This proximity has given rise to a prominent place among science fiction writers, being the stage for an episode of the Star Trek series.

Capella is also the subject of a well-known book on Spiritism. However, to this date, no planet has been detected orbiting any of the four components of Capella.

What we do know is that the yellow giants are already at an advanced stage of its evolution and that in a few million years it will expand even further, becoming red giants. It will remain one of the brightest stars in the sky for a long time.

In Auriga, we find 3 objects from Messier’s catalog: the clusters M36, M37, and M38. The clusters have different ages. The youngest is M36, only 25 million years old. With several bluish stars, its appearance at the telescope is very reminiscent of the famous Pleiades.

M38 has intermediate age. Formed approximately 300 million years ago, it no longer displays luminous blue stars, but it still has a large number of yellow stars like our Sun.

M37 is the oldest of Messier’s objects in Auriga. It was formed 500 million years ago and has at least 500 stars, some of which have already reached the red giant stage. It is located in the opposite direction to the center of our galaxy.

M36, M37, and M38 were first identified in 1654 by Italian astronomer João Batista Hodierna. Born in Sicily, Hodierna divided his time between activities in the church of Palma di Montechiaro and the study of the Universe. He was one of the first astronomers to observe the sky with a telescope.

We can say that Hodierna was the precursor to Messier’s work. More than a century before the Frenchman, Hodierna produced a catalog of about 40 nebulous-looking objects that could be mistaken for comets, exactly the same motivation that led Messier to start his catalog.

Treasures in Taurus

Completing the hexagon is Aldebaran, the brightest star in Taurus (the Bull). Its name means “the follower” in Arabic, a mention of the fact that Aldebaran is near the Pleiades and always seems to follow this star in the sky.

Aldebaran stands out from the rest of the stars we see in the sky due to its reddish color, an indication of its temperature. Its surface is colder than that of the Sun, about 3600 kelvin.

When looking at Aldebaran we are seeing our own future. It is in a more advanced evolutionary stage that our Sun will not reach until billions of years from now.

The hydrogen in the Aldebaran core has already been consumed by the nuclear reactions that make a star shine. When that happened, the star underwent a transformation, greatly increasing its size. Despite having only 50% more mass than the Sun, Aldebaran’s diameter is 40 times larger, equivalent to the size of the orbit of the planet Mercury.

In Taurus, we find two of the most famous objects in Messier’s catalog, including the very first. M1 was observed by Charles Messier in 1758 and inspired him to compile his catalog of smoky-looking objects that could be mistaken for comets. Also known as the Crab Nebula, it is the first object in Messier’s catalog and the only supernova remnant on that list.

Stars with more than eight times the mass of the Sun finish its evolution with an extreme event called a supernova. A supernova is the explosion of a high-mass star, which occurs when the star’s internal pressure can no longer support its own weight. The outer layers of the star collapse and compress the matter in the stellar core to densities so high that exceed the density of an atomic nucleus.

Since it is no longer possible to compress the matter, the only possible movement is outward. The outer layers are then ejected violently into space at incredible velocities. The process releases immense energy that for some days shines more than an entire galaxy.

This is exactly what happened on July 4, 1054, when astronomers in Asia recorded the appearance of a new and bright star in Taurus. It was so bright that it could be seen with the naked eye for three weeks, even during the daytime. The event was also recorded by Native American peoples, but curiously there are no confirmed records in Europe, which at the time was at the height of the Middle Ages.

When we point a telescope at the region of this explosion, we find the nebula itself, composed of gases ejected when the star exploded. At the center of the nebula is what remained of the exploding star: a neutron star, an extremely dense and compact object. It concentrates the mass of a star like the Sun in a sphere only 30 km in diameter.

Neutron stars like the one found in the center of this nebula have intense magnetic fields, and spin quickly, completing a rotation in a fraction of a second. They are intense sources of radio waves, which reach Earth in pulses as if it were a navigation beacon. This led to the popular designation for these objects: pulsars.

Today, astronomers know about 1100 pulsars, and the Crab Pulsar is one of the most important, as it was the first one to be related to a supernova explosion. In addition to radio waves, pulsars also emit intensely in X-rays and gamma rays but are not very bright in visible light.

If you have a telescope, you can try to locate the Crab Nebula, near star Zeta Tauri, at the tip of the bull’s horn. It is necessary to have a telescope with at least 10 cm of aperture to be able to see the nebula, which will appear as a dim, pale cloud.

Messier’s other object in Taurus is the Pleiades, object number 45 in the catalog. It is perhaps the most splendid star cluster in the sky. Its brightest stars were named after the seven sisters of Greek mythology, daughters of Atlas and Pleione.

Several other cultures have legends about this cluster. The Brazilian indigenous people call it Seixu. The appearance of Seixu at dawn indicates the start of the rainy season.

The Pleiades are 440 light-years away from Earth and were formed 100 million years ago. In long-exposure photographs, it is possible to observe a mist between the stars.

For a long time it was believed that this material was the remains of the gas that formed the stars, but the most accepted explanation today is that it is an unrelated cloud of gas and dust that is passing through the cluster.

In total, the Pleiades have about a thousand stars, which will remain together for a further 250 million years before dispersing across the galaxy.

The cluster can be easily seen with the naked eye even from urban locations, between the constellations of Taurus and Aries. Because it occupies a large area in the sky, the Pleiades are best seen with binoculars or low-magnification instruments. High magnifications will show only a few members of the cluster.

What to see in the sky in March

20/3: Welcome Back Sun

The Sun returns to the north celestial hemisphere at 9:37 (Lisbon time), and will not cross the celestial equator again until September 22, 2021. It is the start of spring in the northern hemisphere, and autumn in the southern hemisphere.

5/3: Meeting at Dawn

The planets Mercury and Jupiter make a close conjunction this morning, with Saturn watching from afar. Look east 1 hour before sunrise.

10/3: The Moon and Three Planets

The moon, almost new, joins the trio formed by Mercury, Jupiter and Saturn on the eastern horizon, signaling a beautiful start to the day.

Next week …

The last part of the Theme of the Month brings some northern constellations placed in prime observing position. See you there!

The Winter Sky – Part 4

Northern Attractions

Concluding the series of articles on the Winter Sky, we will visit some constellations near the north celestial pole, which are visible during the early evening during the winter.

The Queen and the King

Our first stop is at Cassiopeia. In Greek mythology, Cassiopeia was a vain queen, married to King Cepheus, and mother of Princess Andromeda. The legend tells that Cassiopeia angered the god Poseidon after claiming that her daughter was much more beautiful than the Nereid nymphs.

As punishment, Poseidon condemned Cassiopeia to revolve around the north celestial pole for eternity, trapped on her throne. Cassiopeia hangs upside down for half of the time, hanging on to keep from falling.

Cassiopeia is one of the 48 original constellations listed by the Greek astronomer Claudio Ptolemy in his famous work Almagest. Its main feature is the figure formed by its five brightest stars. Depending on the time of year, this figure resembles the letters W or M.

Cassiopeia hosted a remarkable event in the history of Astronomy. It was in this constellation that, in 1572, the famous Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe observed a star that was not in the celestial charts. Haunted by the apparition, which remained visible in the sky for a year and a half before disappearing, he coined the term “stella nova”, Latin for “new star”.

Tycho’s new star was a supernova explosion, the catastrophic end of a star many times more massive than our Sun. Today, all that remains of the explosion is a nebula with intense emission of radio waves and X-rays. Another supernova was observed in Cassiopeia in 1660, also an intense source of radio waves.

In Cassiopeia, we find two stellar clusters from Messier’s catalog. The most famous is M103, one of the last to be added to the catalog in 1781. Messier used observations from his collaborator Perre Mechain, who contributed to the discovery of at least 31 of the 110 objects in the catalog.

At a distance of 9 thousand light-years from Earth, M103 is one of the most distant open star clusters known. It is quite young, having formed only 25 million years ago. It has at least 200 members, the brightest being blue and red giants.

In the same field, we find the bright double star Struve 131, though it is unassociated with the cluster. M103 is easy to locate in the sky and can be observed even with binoculars. It is located near Rucbah, one of the stars that form the letter M.

The other Messier object in Cassiopeia is M52, an open star cluster located in a rich starfield. Contains about 200 stars formed 35 million years ago.

Around this area is another constellation associated with the Cassiopeia legend: Cepheus, the king of Ethiopia and Cassiopeia’s husband.

The most famous star in this constellation is Delta Cephei, a prototype of a very special class of variable stars, with fundamental importance in the development of modern astronomy. Its brightness varies in an extremely regular manner, increasing and decreasing about 50% in just over 5 days.

This behavior, first noticed in 1784 by English astronomer John Goodricke, was soon observed in other stars. Stars whose brightness varies in this way are named Cepheid variables.

Cepheids are important in astronomy because the period of brightness variation is directly linked to the total luminosity of the star. The brighter the star, the longer it takes for the brightness variation to complete a full cycle.

This relationship between period and luminosity was discovered in 1908 by American astronomer Henrieta Leavitt, and it is still one of the main distance indicators in the Universe. It was used by Edwin Hubble in 1929 to discover that the Universe is expanding.

The Hero

Also next to Cassiopeia is Perseus, a constellation representing one of the most famous heroes of Greek mythology.

Perseus is the protagonist of countless adventures. The most famous involves his battle with Medusa, one of the three Gorgons sisters, horrendous beings that petrified everyone with their gaze.

Perseus was asked by King Polydetes to kill Medusa and bring her head back. For this fearsome combat, Perseus obtained special equipment. Goddess Athena gave him a bronze shield, so polished that could serve as a mirror. Hermes gave him a diamond sword and winged shoes. And Hades presented him with a helmet that made him invisible.

Upon reaching Medusa’s lair in Mount Atlas, Perseus followed the trail of petrified men and animals, protected by his invisibility helmet. Arriving at Medusa’s hideout, he waited until she slept. In order not to be turned into stone, Perseus approached her looking only at the reflection in the shield, and beheaded her. To his surprise, at this moment the winged horse Pegasus emerged from Medusa’s womb. Perseus mounted Pegasus and fled.

On the way back, Perseus saw Princess Andromeda chained to a rock, about to be devoured by Cetus, the sea monster. Perseus showed Medusa’s severed head to Cetus, turning it to stone, thereby saving the maiden and later marrying her.

As a constellation, Perseus has no bright stars. The most famous one is Algol, a variable star. Every 3 days, the brightness of Algol starts to decrease. After 4 hours, it is only half as bright as it was initially. It remains dim for about 20 minutes and then returns to its normal brightness. This strange behavior earned Algol its nickname “Devil Star”.

It took many years to discover the true cause of Algol’s blackouts. In 1728, English astronomer John Goodricke found that Algol is a binary star, with one component small and bright, and the other large and dimmer. When the largest star passes in front of the brightest, an eclipse occurs, and the system’s overall brightness decreases. Today we call stellar systems like Algol eclipsing binaries.

Perseus is traversed by the plane of our galaxy, the Milky Way, and has a considerable number of deep-sky objects. The best known are h and chi Persei, collectively knows as the Double Cluster.

This binary cluster contains thousands of stars formed 13 million years ago. Despite being more than 7 thousand light-years from Earth, it can be easily seen with the naked eye in dark sky locations. At the telescope, it is one of the most inspiring views that Astronomy can provide.

For some unknown reason, the Double Cluster is not represented in Charles Messier’s catalog. The only star cluster of Perseus on this list is M34, located near the border with Andromeda.

M34 is one of Messier’s nearest objects to Earth. It is 1500 light-years from us and can be easily seen with binoculars. Formed 200 million years ago, it is at an intermediary evolutionary stage, having already lost its most massive members. At least 19 white dwarfs have already been identified in M34.

To locate this cluster, draw a line between stars Algol and Almach (in Andromeda). M34 will be midway through that line. A good exercise for those who are learning to navigate the heavens.

The other Messier object in Perseus is planetary nebula M76. Messier added the object to his list in 1780, but its peculiar structure was only identified in 1918 by Heber Curtis.

M76 is a bipolar planetary nebula, about 1.2 light-years across, and distant 2500 light-years from Earth. Its structure is similar to Messier 27 in Vulpecula (The Fox), earning M76 its name “Little Dumbbell Nebula”.

Its central star is a white dwarf with a surface temperature of almost 70,000 degrees. The ultraviolet light emanating from the star excites the atoms of the surrounding nebula, making it shine in characteristic colors. Long-exposure photographs reveal a more extensive halo around the object, expanding at 40 km / s.

Locating M76 in the sky is a challenge even for experienced astronomers. It is a small, low surface brightness object, requiring a medium-sized amateur telescope and a very dark sky. From star 51 Andromedae, head north to the faint star Phi Persei. M76 is about a degree from this star.

Perseus is also well known because of its famous meteor showers, the Perseids, which happens in August. Visit my article “The Summer Sky” to know more about this meteor shower.

The Princess

To cap this tour of the northern constellations, meet Andromeda. Daughter of Cassiopeia and Cepheus, Andromeda was a young woman of extreme beauty, more beautiful than the Nereids (the Sea Nymphs), who were daughters of Poseidon.

Envious of Andromeda’s beauty, the Nereids asked their father to send the sea monster Cetus to decimate the coast of Ethiopia, (a region of Israel, not the African country). Fearing for his kingdom, Cepheus consulted an oracle, who told him that the only way to prevent destruction would be to sacrifice his daughter to the monster.

And Cepheus did so, chaining the young Andromeda to rocks on the coast. By now, you know the rest of the story: Perseus turned the monster into stone, saved the beautiful maiden, and married her.