Meteoritos: fragmentos do céu

Meteoritos: fragmentos do céu

Ao viajar pelo espaço, a Terra “recolhe” mais de 100 toneladas de material por dia. Desta quantidade, só uma pequena parte é encontrada e estudada. Mas foram esses fragmentos rochosos, os meteoritos, que nos forneceram os primeiros dados sobre a composição dos objectos extraterrestres que fomos conhecendo, e sobre a história do Sistema Solar. O que são, de onde vêm, onde e como se encontram, e como se estudam – estas são algumas das questões que vamos aqui explorar ao longo das várias semanas do mês de maio.

Autor: José Saraiva

José Saraiva é geólogo de formação. Licenciado pela Univ. Coimbra, fez um Mestrado no IST e por lá ficou muitos anos como bolseiro de investigação. Marte e outros planetas foram alvo de várias investigações sob o prisma da Análise de Imagem ao longo desses anos. Actualmente é Coordenador de Projectos no NUCLIO, de que é colaborador há muitos anos.

Nota: o autor do texto não escreve segundo o novo Acordo Ortográfico.

⬇︎ Clique, abaixo, para ler cada uma das partes deste tema

Meteoritos: fragmentos do céu – Parte 1

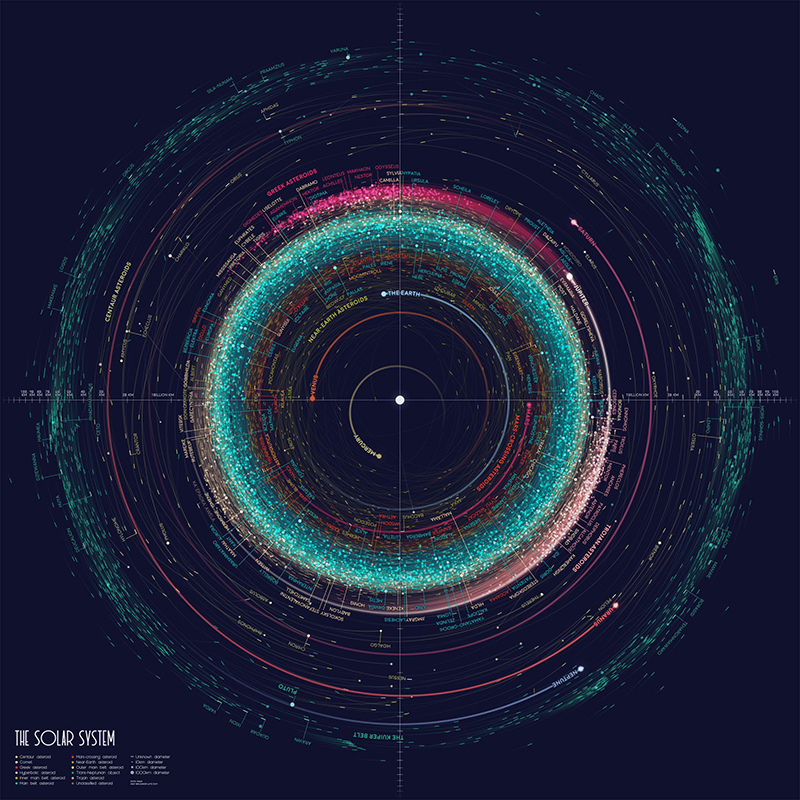

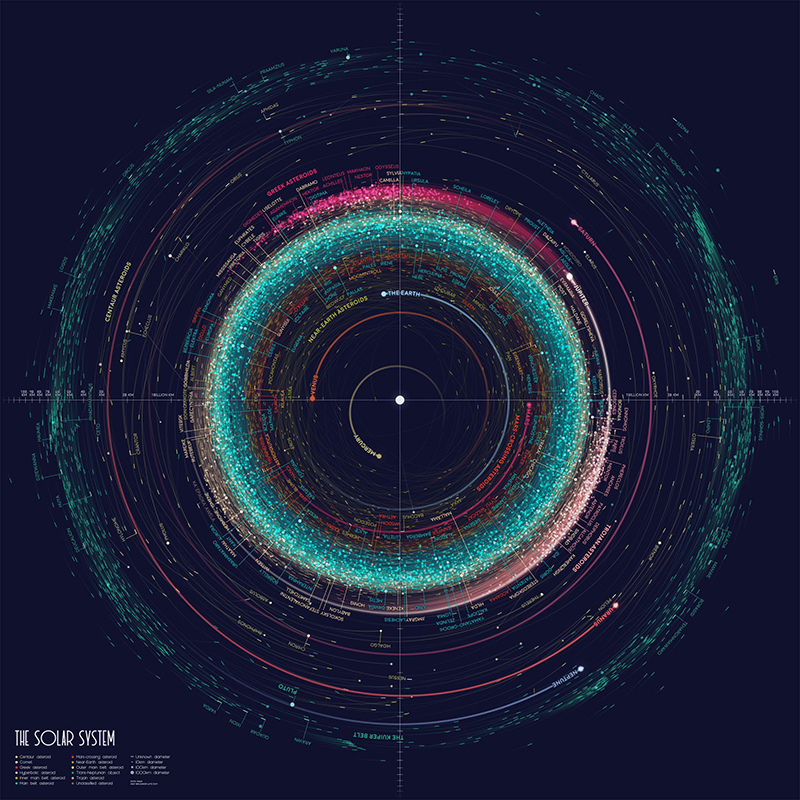

O Universo é muito grande. Mesmo o Sistema Solar, que é apenas um cantinho minúsculo desse Universo, é muito grande. Para nós, seres humanos, mas também para os planetas, mesmo aqueles, como Júpiter e Saturno, a que chamamos gigantes. E portanto está praticamente vazio. Contudo, eles andam por aí: os planetas e planetas-anões, os seus satélites, os asteróides e os cometas, e por aí fora, até aos mais pequenos grãos de poeira interplanetária.

Como nós, humanos, gostamos – ou mais do que isso, precisamos – de dividir as coisas em categorias, classes, grupos, por naturezas, dimensões e por aí fora, também aplicámos esse princípio a tudo o que fomos identificando lá por cima (ou por baixo, ou pelo lado – o espaço está para onde quer que nos viremos…)

E assim temos os tais planetas, planetas-anões, satélites… coisas que andam nas suas “rondas” há muitos anos, bem comportadas, longe da Terra, e que não esperamos ver a chocar com o nosso planeta. (Embora o caos reine nas órbitas planetárias, quando vistas a muito longo prazo; e tenhamos razões para pensar que nos primeiros tempos do Sistema Solar choques dessa magnitude possam ter acontecido.)

Depois temos asteróides e cometas. Objectos de dimensões mais pequenas, com distribuições até certo ponto conhecidas, mas que são muito numerosos – e, portanto, apesar de sabermos dos grupos e regiões mais frequentadas, não estão todos identificados. Estes são possíveis visitantes ao nosso planeta, e podem ter nele efeitos de grande monta, como nos mostram algumas cicatrizes de impactos ainda visíveis na superfície da Terra… e o desaparecimento de alguns grupos de animais no passado (ou, pelo menos, assim o pensamos).

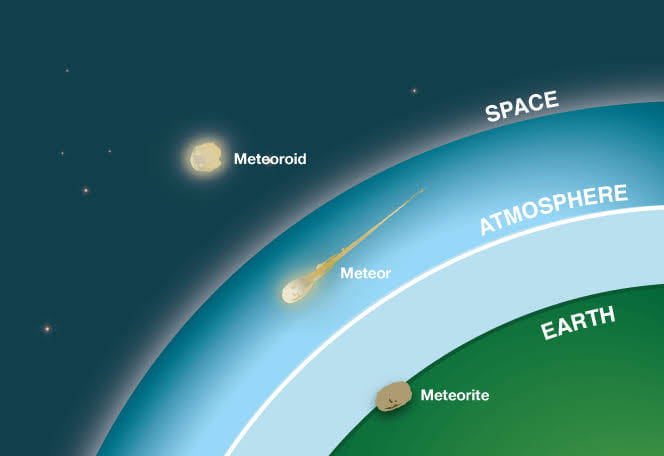

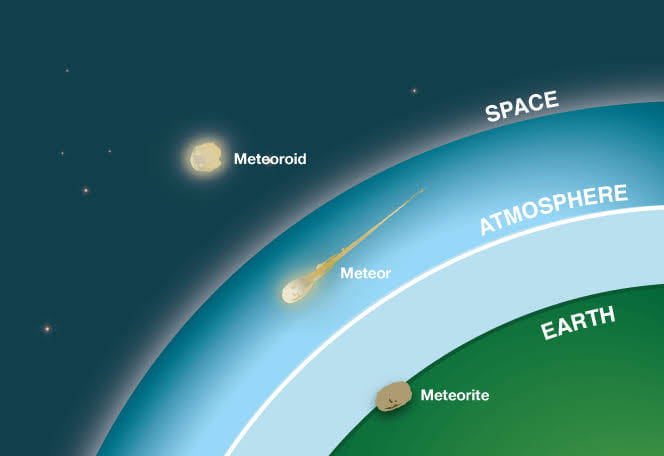

Mas há muitos mais objectos de pequena dimensão, a que não ficaria bem chamar asteróides… mas temos que lhes arranjar um nome: meteoróides. Claro que é fácil ficarmos enredados nesta confusão de classificações. Que tamanho tem afinal um meteoróide? Bom, fiquemos com a classificação da IAU (União Astronómica Internacional): entre 30 µm e 1 m. Se for mais pequeno… é um grão de poeira. Mas o fundamental é perceber que um meteoróide é um objecto que viaja pelo espaço interplanetário.

Qual é a origem dos meteoritos? Façamos uma lista: podem ser grãos pré-solares – afinal de contas, a matéria que constitui o Sistema Solar não surgiu do nada; podem ser grãos vindos de outro sistema; podem ser grãos condensados logo no início da história do Sistema Solar e nunca incorporados em objectos maiores; podem ser grãos resultantes dos processos que levaram à formação dos planetas e outros objectos de grande dimensão (ou seja, colisões); podem ser grãos resultantes de processos mais tardios – colisões aleatórias entre asteróides, passagens de cometas pela zona interior do Sistema Solar, impactos em planetas com projecção de material para o espaço; e podem por fim ser fragmentos de objectos de maior dimensão que se desfizeram… quem tiver mais ideias, é juntá-las à lista. Mas para resumir, podem ser meteoróides, ou fragmentos de asteróides,

O passo seguinte é quando eles encontram a Terra… Uma série de factores entram em jogo: velocidade relativa, ângulo de penetração na atmosfera, natureza do objecto… e a sua dimensão, claro. Uma vez que a Terra é um planeta com uma atmosfera densa, qualquer objecto que a encontre vai enfrentar resistência, atrito… e vai sofrer as consequências.

Se o objecto em questão for de dimensões reduzidas, vai aquecer e brilhar, e ser visível no céu (nocturno…) por breves instantes, até se “gastar”. Isso acontece a uma altitude superior a 75 km, e isso é um meteoro, ou uma estrela cadente. Por vezes estes objectos chegam em grupos e dão origem a “chuvas de meteoros”, normalmente relacionadas com cometas, que ocorrem quando a Terra passa por uma zona do espaço onde passou um cometa, que deixou um rasto de partículas.

Objectos maiores também sofrem, evidentemente, um aquecimento por razões aerodinâmicas, e podem conseguir chegar à superfície do planeta, ou podem “desfazer-se” ao longo da sua passagem pela atmosfera, espalhando fragmentos que sofrem uma grande desaceleração e que, sendo meteoritos, não embatem com a velocidade suficiente para criarem crateras de impacto. Isso acontece com objectos maiores ainda, embora também esses sofram alguma desagregação e produzam chuvas de fragmentos. Na realidade, por muito que tentemos prever o comportamento destes objectos, os exemplos indicam-nos que isso não é fácil nem fiável.

Vejamos quatro casos relativamente recentes:

A 15 de Setembro de 2007, houve notícia de um impacto no Peru, perto do lago Titicaca. O resultado foi uma cratera de cerca de 15 m de diâmetro. O objecto deveria ter pelo menos 3 m de diâmetro, mas na realidade ele estava a partir-se, tendo produzido um meteoro e um estrondo, e foram recuperados pequenos fragmentos rochosos. Factos bizarros? Os habitantes locais que se aproximaram da cratera pouco depois do impacto sofreram problemas de saúde cuja causa nunca foi completamente esclarecida (provavelmente inspiração de compostos ricos em enxofre). Aparentemente, uma cabra e um lama foram encontrados mortos nas proximidades. Mas, mais importante, em teoria este objecto nunca devia ter sobrevivido à passagem pela atmosfera de forma a provocar uma cratera. Os cálculos indicam que, apesar de uma forte desaceleração, o impacto se deve ter dado a uma velocidade superior a 3 km/s.

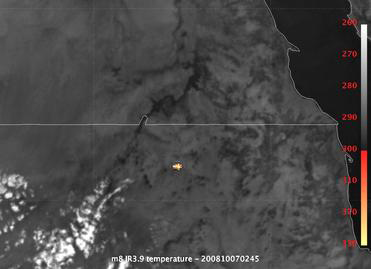

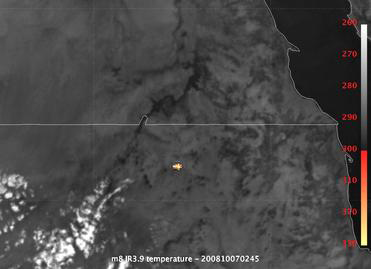

A 7 de Outubro de 2008, um objecto que tinha sido identificado algumas horas antes, a aproximar-se da Terra, explodiu por cima do deserto do Sudão. Era um asteróide, baptizado 2008TC3, de cerca de 4 m de diâmetro, que penetrou na atmosfera a cerca de 13 km/s e se desintegrou a 37 km de altitude, fazendo chover (atenção: não foi uma chuva de meteoros!) pelo menos uns 600 meteoritos, fragmentos, sobre o deserto – sem criar crateras de impacto. Apesar da tremenda libertação de energia quando da destruição do asteróide, não houve danos, dado o carácter remoto da área e a altitude a que ela ocorreu.

Avancemos até 15 de Fevereiro de 2013. Em Chelyabinsk, Rússia, foi observado em pleno dia um bólide, ou bola de fogo, um meteoro de grandes proporções, mais luminoso do que o Sol. O objecto devia ter cerca de 20 m, e penetrou na atmosfera a cerca de 20 km/s e num ângulo raso. Não resistiu, e explodiu a cerca de 30 km de altitude. A onda de choque provocou estragos na cidade russa, a alguns quilómetros de distância. Também neste caso inúmeros fragmentos chegaram à superfície da Terra, como meteoritos, mas sem darem origem a crateras de impacto.

E há poucas semanas, a 28 de Março de 2020, uma estranha explosão atingiu uma povoação nigeriana. Algumas explicações precoces apontavam para uma explosão de materiais químicos com intervenção humana, mas acabou por prevalecer a ideia de que se tratou de um impacto meteorítico, que criou uma cratera de cerca de 21 m de diâmetro. Embora não estejam disponíveis muitos dados sobre este impacto, o mais provável é que tenha sido um objecto de alguns metros de diâmetro, fortemente desacelerado (testemunhas dizem tê-lo visto a cair) e em desintegração, que deixou, para lá da cratera, inúmeros fragmentos que serão por certo estudados no futuro.

O que podemos concluir? Que há fragmentos rochosos vindos do espaço que atingem a superfície da Terra, mas que nem todos provocam crateras de impacto; ou pela sua dimensão (e não falámos de micrometeoritos, que, podemos dizer, “flutuam” lentamente até à superfície) ou pelas circunstâncias que rodeiam os últimos instantes das suas viagens. Todos eles são meteoritos, o que hoje é fácil de reconhecer. Mas nem sempre foi assim.

Meteoritos: fragmentos do céu – Parte 2

No princípio do século XVIII, Newton declarou que o espaço interplanetário estava necessariamente vazio. Isso, afirmado por Newton, só podia querer dizer que os relatos de pedras a cair do céu eram histórias da carochinha, saídas da imaginação e da credulidade de um povo ignorante… ou então que elas tinham de facto origem na Terra. Porque não havia falta de relatos desse género.

Na Antiguidade ocidental existem inúmeras histórias, mais ou menos mitificadas, sobre quedas de meteoritos. Mas enfim, o mundo era visto de outra forma, e os deuses tudo podiam, e eram dados a brincar com a Humanidade. Nessa altura, não era sabido que entre alguns povos primitivos era habitual recorrer-se a ferro meteorítico para obter algumas ferramentas de metal. Ou que no túmulo de Tutankhamon havia um punhal feito desse mesmo material vindo de longe.

E também não se soube, até muito mais tarde, que ao início da noite de 19 de Maio de 861, no Japão, uma dessas pedras vindas de longe – do céu, de facto – caiu no jardim de um templo. Entre muitas outras coisas, os japoneses fazem caixas muito delicadas, e são grandes fãs da permanência. O meteorito foi assim guardado numa caixinha pelos monges, e por lá ficou… mais de mil anos. Até que, no século XX, a história foi redescoberta e divulgada, e a pedra foi estudada e identificada como um meteorito rochoso. O mais antigo cuja queda foi registada e que ainda existe.

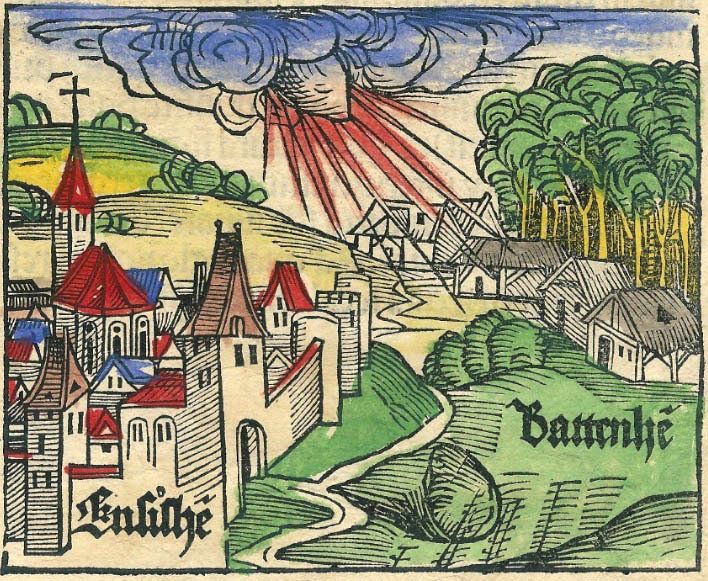

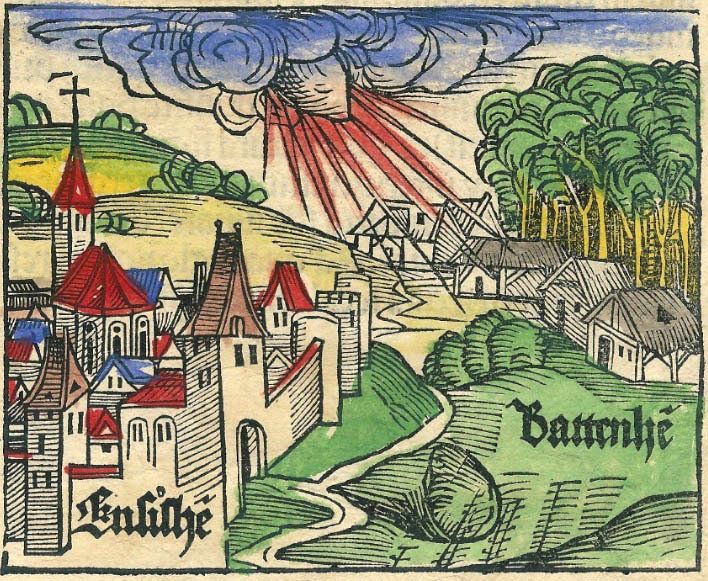

Entretanto, na Europa, muito tinha mudado. Em 1492 (a 7 de Novembro), um outro meteorito caiu, este na Alsácia, junto à cidade de Ensisheim. Houve testemunhas, e a pedra foi recolhida (e partida em muitos bocados – mas sobrou uma massa de 56 kg, menos de metade do original). Claro que o evento foi interpretado como um presságio para o resultado de batalhas, desporto muito popular à época naquela “animada” parte da Europa… Como a imprensa tinha sido inventada ainda havia pouco, o acontecimento foi divulgado em folhetos e usado para fins propagandísticos. Quanto à origem e natureza do objecto, isso pouco importava, na realidade. Era apenas a vontade de um deus.

Só no fim do século XVIII uma série de quedas foram observadas e registadas por toda a Europa, e deram origem a uma tremenda discussão. Uma queda em 1766, na Itália, levou à publicação de um livro em que se sugeria uma explicação científica para o fenómeno: era uma rocha lançada para cima por uma explosão vulcânica. Mas houve quem não concordasse e propusesse outra hipótese: a rocha teria sido lançada para o céu por um relâmpago. Em 1789, Lavoisier, por seu lado, defendeu uma ideia que já vinha de trás, a de que estas rochas se podiam formar (agregar) em plena atmosfera. (Teria perdido a cabeça? Nessa altura, ainda não…)

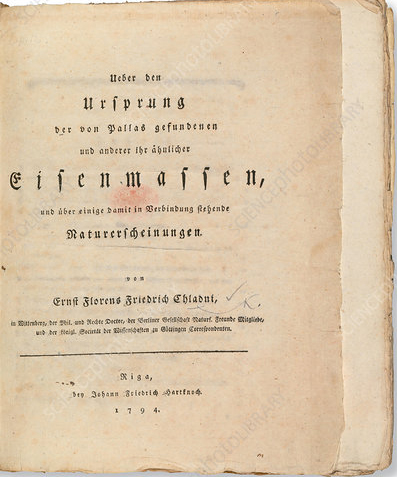

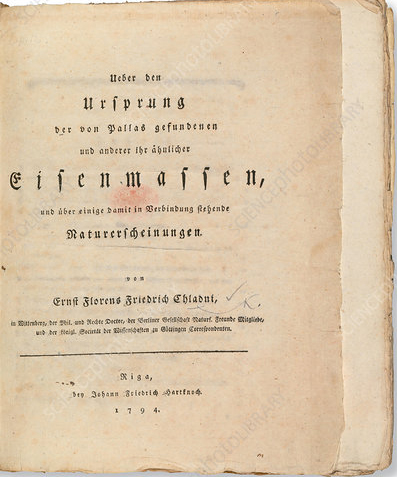

Mas em 1794, Chladni, um físico alemão (muito conhecido pelos trabalhos na Acústica), publicou uma obra sobre as massas de ferro encontradas aqui e ali, e defendeu que elas tinham origem extraterrestre – e fez o possível por demolir todas as outras explicações. Estava fundada a ciência meteorítica.

Um ano depois caiu um grande meteorito na Inglaterra, e em 1796 surgiu o primeiro livro em inglês sobre os meteoritos. Na França, foi preciso uma verdadeira chuva de quase 3000 fragmentos meteoríticos, em 1803, para convencer a comunidade científica de que, de facto, havia pedras a cair do céu.

Ainda assim, as explicações mais aceites continuaram a ser a acreção atmosférica e a origem vulcânica (mas agora da Lua!)… até que os asteróides começaram a ser descobertos (a partir de 1801). A meio do século XIX a origem dos meteoritos como objectos extraterrestres estava bem estabelecida. A discussão passou a ser se eles vinham dos asteróides, ou do espaço interestelar – e só foi resolvida com a análise das órbitas a partir dos registos feitos por câmaras automáticas. Os meteoritos são agora reconhecidos como objectos cosmológicos, astronómicos, físicos, geológicos, químicos, mineralógicos e meteorológicos (o que foi primeiro afirmado em 1858). E como testemunhas privilegiadas da história do Sistema Solar.

Esta mais que resumida versão de uma história fascinante e cheia de peripécias tem ainda outro ângulo. Muito do conhecimento sobre os meteoritos teve por base o estudo de amostras que foram sendo reunidas em colecções ainda hoje importantes, em Viena, Berlim, Londres e Paris, mas também na Rússia e nos EUA. Neles se podem observar amostras de alguns meteoritos famosos por diversas razões.

O Museu de História Natural de Viena possui uma das mais antigas e extraordinárias colecções de meteoritos. O edifício só por si vale a visita, mas na realidade, para quem aprecia o tema, são os meteoritos que brilham.

Deixemos as imagens falar.

Hoje em dia, continuam a ser organizadas expedições para recolher meteoritos. Há na superfície da Terra locais onde eles podem ser mais facilmente identificados – os desertos. Particularmente os gelados – e a Antártida é um destino regular para expedições de recolha, dado que os meteoritos, pedras isoladas nos campos de gelo, saltam à vista. Nos desertos arenosos há mais rochas, e o verniz do deserto pode ter um aspecto muito semelhante à crosta de fusão que cobre a superfície de muitos meteoritos…

Claro que há uma questão ainda em aberto: mas os meteoritos são todos iguais? Não. De todo. Como veremos.

Meteoritos: fragmentos do céu – Parte 3

Toda a gente sabe que todos os meteoritos são magnéticos. Todos? Não. Há alguns que resistem ainda e sempre ao imã que se tenta pegar a eles (sim, é uma referência asterixiana)… Além disso, há rochas terrestres que também são magnéticas. Dá ideia de que viemos parar a meio de uma discussão sobre a composição dos meteoritos… Se calhar é melhor começarmos pelo princípio.

Vamos deixar em primeiro lugar uma divisão primária que nada tem a ver com a composição, e apenas com as circunstâncias da identificação: um meteorito pode ser visto a cair – é uma “queda” – ou ser apanhado do solo mais tarde – é então um “achado”.

Passemos a coisas mais importantes. Muita gente está convencida de que os meteoritos são pedaços de metal. Não. Há de facto meteoritos metálicos, mas também há os que são rochas, aparentemente semelhantes a muitas das rochas que andam por aí ao pontapé (mas não a todas; não há meteoritos feitos de calcário, nem de granito). E depois há os que são uma mistura de metal e rocha. Então porque é que há tanta gente que pensa em metal quando pensa em meteoritos? Bom, encontrar um pedaço de metal pelo solo quando passeamos no campo é menos comum (mesmo usando um detector de metais) do que dar mais um pontapé numa pedra (não o façam, pode haver gente no fim da trajectória!) – portanto, esse pedaço de metal vai atrair bastante mais atenção, e até se pode dar o caso de ser mesmo um meteorito (embora às vezes seja apenas um pedaço de escória de uma fundição pré-histórica)!

E assim os meteoritos metálicos, conhecidos como sideritos, por serem colhidos com maior frequência, são mais numerosos nas colecções reunidas aqui e ali. No entanto, eles representam menos de 10% dos meteoritos cuja queda é observada!!! E agora que se fazem campanhas regulares de recolha em sítios recônditos, o número de meteoritos de outros géneros começa a subir. Os outros, são as tais rochas, e as misturas. Lá chegaremos.

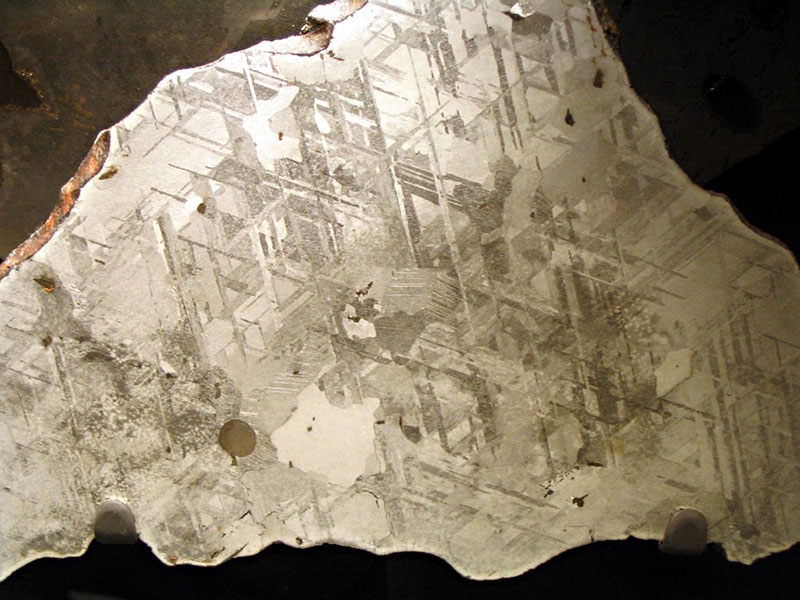

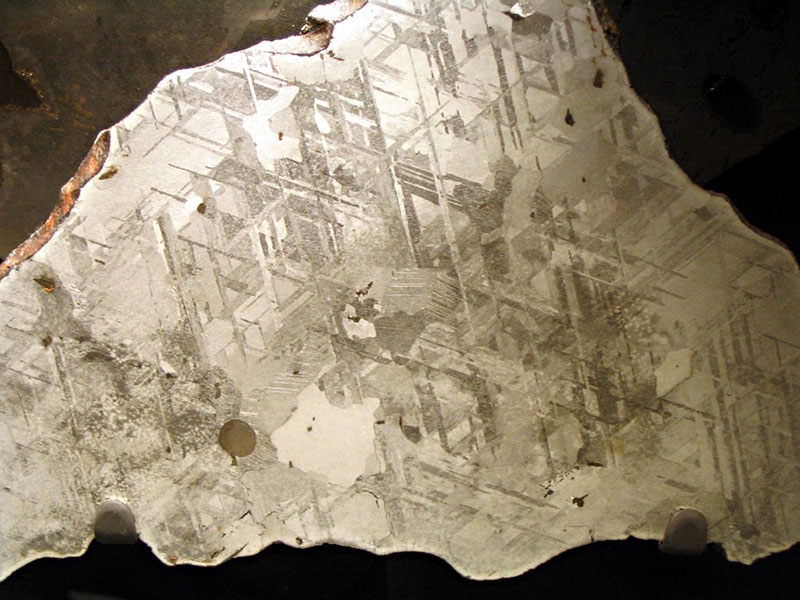

Vamos primeiro arrumar os metálicos. São densos (“pesados”), porque… bom, são feitos de ferro (e níquel) – o que também explica o magnetismo. A quantidade de níquel e a relação entre dois minerais de ferro e níquel permite dividi-los em grupos. Uma antiga classificação baseada na estrutura cristalina desses minerais, deixou de ser usada.

Onde é que existe assim tanto metal sem rocha associada? No interior profundo dos planetas como a Terra – ok, não o vemos nesse caso, porque chegar ao núcleo da Terra só é possível em Hollywood, mas sabemos que a Terra (globalmente) é bastante mais densa do que as rochas que tem na superfície, donde… deve existir algo mais denso lá no fundo. E magnético. Parece um raciocínio circular, mas há boas razões para ele. E vamos ter daqui a uns anos uma missão espacial a um asteróide metálico, chamado Psyche, que nos vai talvez permitir perceber melhor esta história, já que se pensa que esse asteróide corresponde ao núcleo de um antigo proto-planeta.

Esse objecto planetário não apareceu do nada. Cresceu, pela aglomeração de fragmentos menores, até ter tamanho e calor suficiente para se diferenciar – os materiais menos densos (rochas em fusão) vão para cima, os mais densos (metais) para baixo. Mas se agora temos um asteróide só com o metal, onde foram parar as rochas que o deviam cobrir? Provavelmente em resultado de uma colisão, andam por aí, e algumas são meteoritos. Neste e noutros casos, como fizeram parte de objectos de dimensão planetária, é de admitir que os componentes destas rochas tenham estado envolvidos em processos geológicos mais ou menos complexos, e assim elas formaram-se pelo arrefecimento de fracções silicatadas fundidas, com diferentes composições e em diferentes momentos. Ou seja, são basicamente rochas magmáticas, até certo ponto semelhantes às terrestres, mas com maior teor de metais (e, por isso, magnéticas).

Isso vale também para os meteoritos de origem lunar ou marciana, mas nestes casos há um componente que falta (porque Marte e a Lua são bem maiores e mais diferenciados do que os asteróides): o metal – e por isso, estes meteoritos de grande valor científico e económico têm uma menor susceptibilidade magnética.

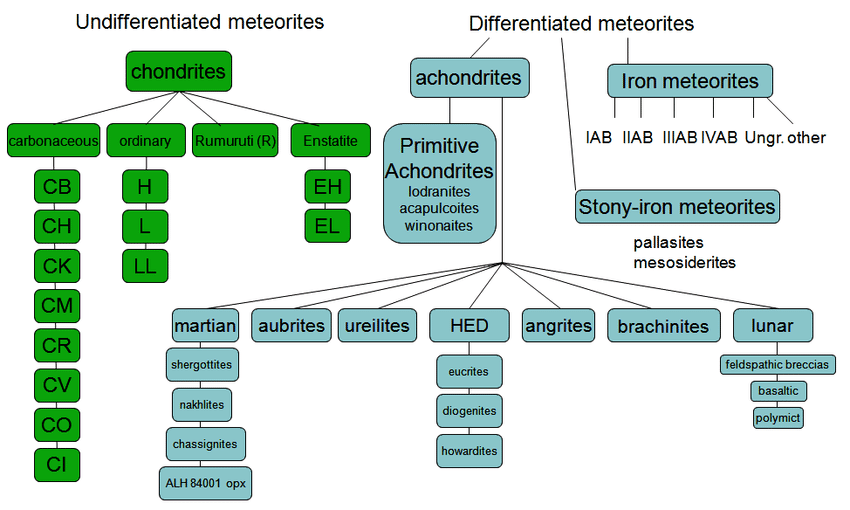

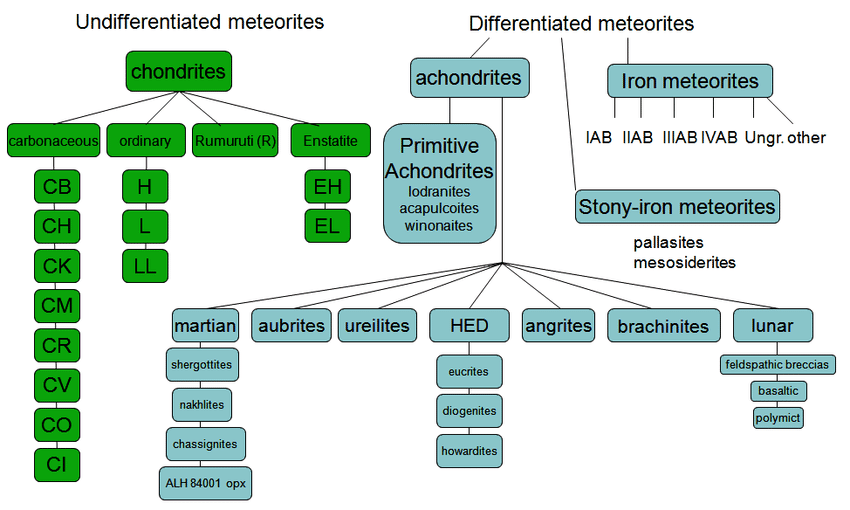

Confusos? Recapitulemos: temos meteoritos metálicos (sideritos), e meteoritos rochosos – os acondritos (rochas magmáticas). Mas ainda temos mais. Há meteoritos rochosos que nunca estiveram envolvidos em processos que levassem a profundas alterações da sua composição inicial (como a fusão e a segregação magmática). São os condritos, e também os há de vários tipos. São estes, aliás, os meteoritos mais numerosos que chegam à Terra.

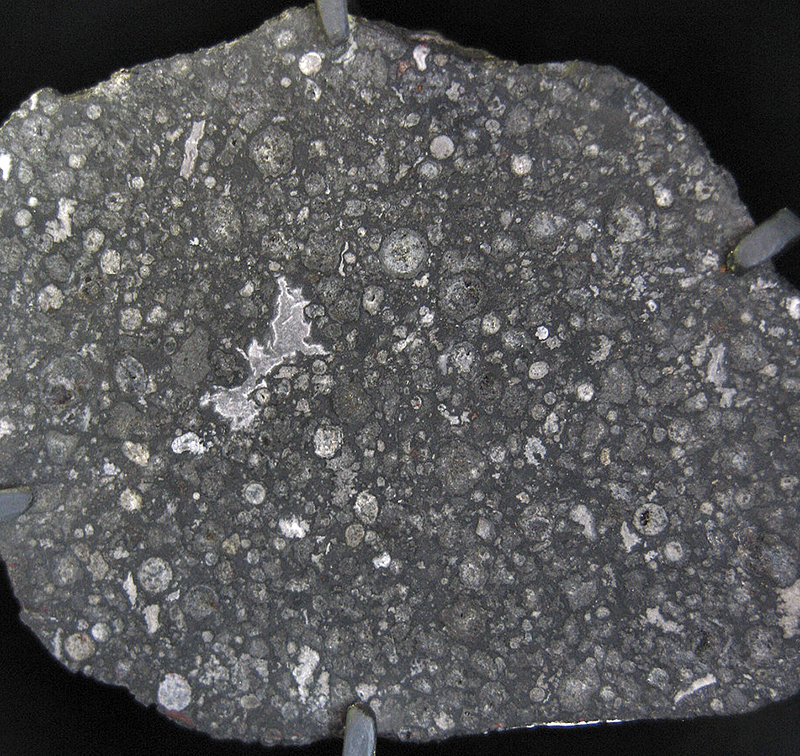

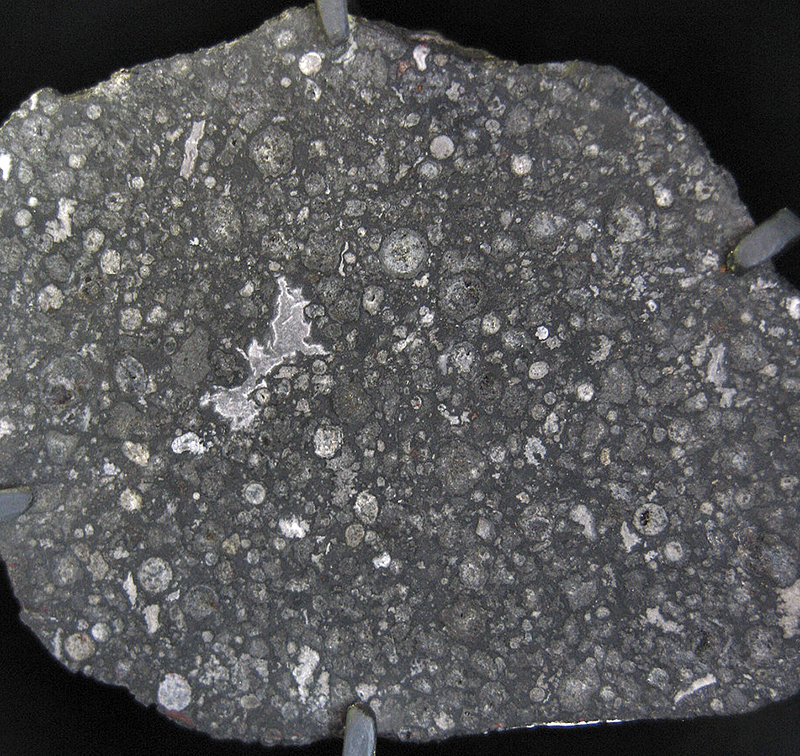

Mas de onde lhes vem o nome? Do facto de conterem grânulos, ou côndrulos, pequenas bolas de material muito antigo. De facto, quando analisados, os condritos têm uma composição global que se assemelha à do Sol (sem hidrogénio e hélio), e daí pensar-se que representam material da nuvem primitiva a partir da qual se formaram os planetas. Entre os condritos, há um grupo chamado condritos carbonáceos que são considerados os mais primitivos. Na realidade, é difícil dizer que temos meteoritos que nunca sofreram nenhuma alteração, que estão tal e qual ficaram depois da condensação e acreção do material na nuvem original, já que mesmo os condritos parecem, em muitos casos, mostrar sinais da passagem de fluidos (como a água).

Temos assim metais de um lado e rochas do outro (não vamos enveredar por uma exploração detalhada dos diferentes subgrupos, já que isso daria para outro Tema do Mês; digamos apenas que as particularidades de composição e de textura levam a dividir tanto uns como outros em inúmeras classes). Mas há ainda outro grande grupo, intermédio: aqueles onde existe uma mistura (por vezes íntima) dos dois componentes, metal e rocha.

Neste grupo avultam duas subdivisões importantes: os pallasitos (não têm nada a ver com o asteróide Pallas, atenção!), talvez os mais belos dos meteoritos, que revelam cristais de olivina numa massa metálica, e as brechas, ou mesosideritos, em que os dois componentes se encontram profundamente misturados – normalmente considera-se que este tipo de meteoritos teve origem numa colisão violenta entre asteróides.

Restam apenas os meteoritos lunares, e os SNCs, meteoritos de Marte – que são de facto acondritos, mas merecem ficar à parte, claro (e também eles não são todos iguais).

Está tudo? Sim e não. Esta visão global dos tipos de meteoritos é deliberadamente pouco detalhada; há alguns subgrupos de que existem muito poucos membros conhecidos, ou mesmo apenas um, o que revela a grande diversidade dos meteoritos.

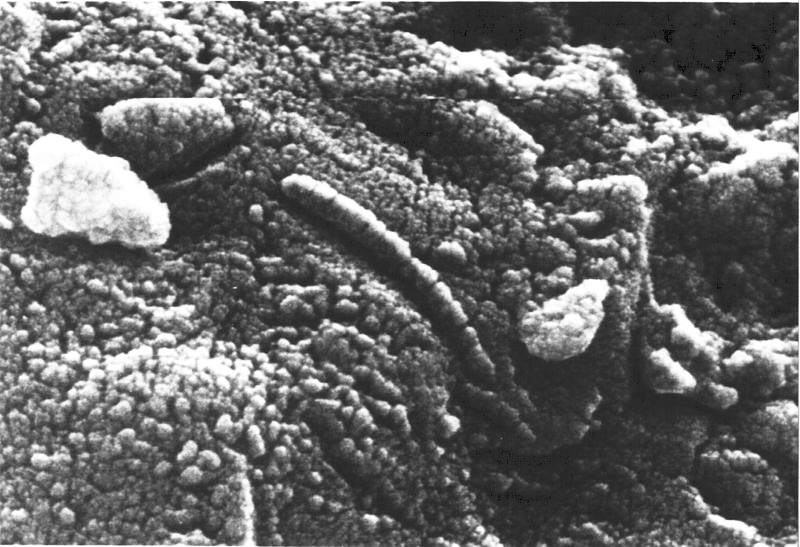

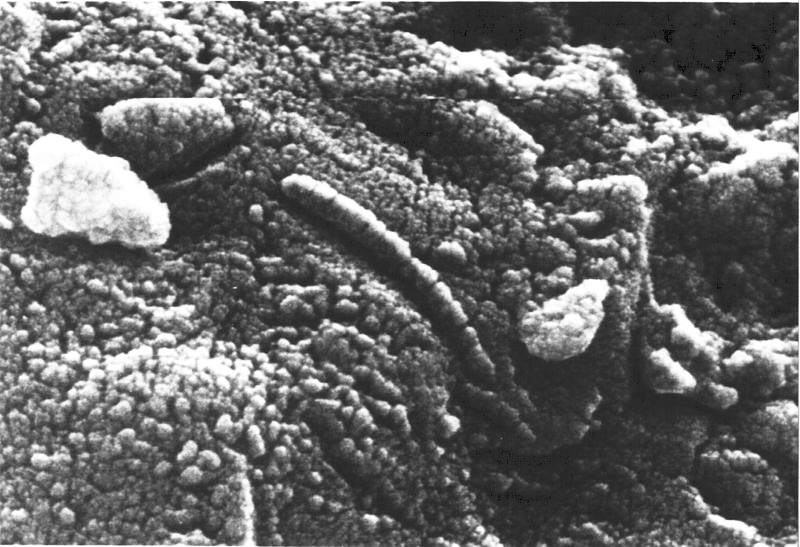

E há sempre a possibilidade de hoje ou amanhã tombar na Terra um meteorito diferente – ou talvez até já tenha caído: abundam histórias sobre meteoritos com matéria orgânica (comprovada), e até mesmo com “microrganismos” (casos debatidos até à exaustão, e geralmente inconclusivos).

Conclusão: não sabemos tudo, nunca saberemos tudo. Não se classificam meteoritos a olhar para uma amostra na mão. Para estudar os meteoritos, usam-se os métodos que se aplicam a outras rochas: microscopia, análise química e isotópica. E é nos resultados dessas observações que se baseiam as inúmeras divisões classificativas.

Convém recordar que foi o estudo dos meteoritos que permitiu concluir que a Terra tem cerca de 4550 milhões de anos de existência (mas essa é outra história que daria pano para mangas). Uma certeza: há ainda muito para descobrir e aprender no mundo dos meteoritos.

Meteoritos: fragmentos do céu – Parte 4

Onde estão os meteoritos que caíram em Portugal? Não é fácil responder a esta questão. Não existe uma verdadeira colecção nacional. No Museu Nacional de História Natural e da Ciência (MUHNAC) há alguns exemplares, mas nunca existiu um esforço concertado de reunir referências, localizações e amostras. Há de facto alguns conhecidos, catalogados, dispersos por Universidades e Museus, mas existem também com toda a certeza alguns espécimes desconhecidos espalhados por aqui e por ali, em escolas, museus locais e casas particulares (na casa da minha avó materna, oriunda do Redondo, havia um belo fragmento de metal cuja história se perdia na bruma do tempo… desapareceu muitos anos antes de eu poder reclamar o meu interesse naquela pedra peculiar).

Há, no entanto, algumas histórias que vale a pena divulgar.

Por exemplo: em 1796, a 19 de Fevereiro, caiu um meteorito perto de Évora Monte. Foi redigido um documento notarial com os testemunhos dos que assistiram ao evento, documento esse que foi traduzido para inglês por Robert Southey, personagem que veio a alcançar relevo nas letras inglesas, e que, à época, viajava pelo país. O meteorito está referenciado nas bases de dados internacionais, com o nome “Portugal”, mas dele não parece restar qualquer fragmento cujo paradeiro seja conhecido. Esta queda aconteceu em pleno período de crescimento da atenção dada aos meteoritos e de mudança de ideias relativamente à sua natureza, e foi a primeira a ser conhecida no país.

Por outro lado, não pode haver dúvidas de que, ao longo de séculos de presença colonial em África e na América do Sul, muitas quedas devem ter sido observadas, alguns meteoritos devem ter sido encontrados – mas, mais uma vez, encontrar referências a esses eventos exigiria um tremendo esforço de pesquisa. Tendo em atenção que o reconhecimento da natureza extraterrestre dos meteoritos só foi realidade no início do século XIX, se nos reportarmos aos números oficiais, isto é, catalogados (no caso, no Catalogue of Meteorites, 5ª Edição, de Brady, publicado em 2000; ou no site da Meteoritical Society), podemos tentar obter alguns dados… mas não conseguimos grande coisa.

Em Angola temos registo de três quedas, relativamente recentes (em 1961, 1966 e 1974), e um achado. Nenhum dos outros países de língua oficial portuguesa (Moçambique, Guiné-Bissau, Cabo Verde e S. Tomé e Príncipe) tem qualquer registo – o que, no caso de Moçambique em particular, se afigura bizarro, dada a grande dimensão do país. No Brasil, os números são melhores, com 21 quedas e 31 achados registados (a independência do Brasil surgiu na década de 20 do século XIX, pelo que todos eles são já do período pós-colonial).

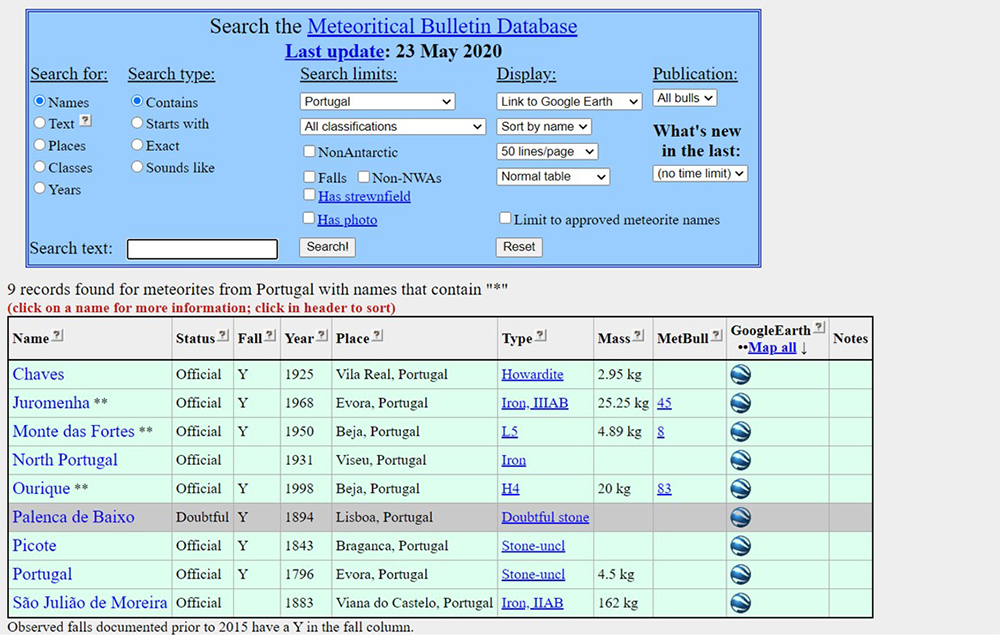

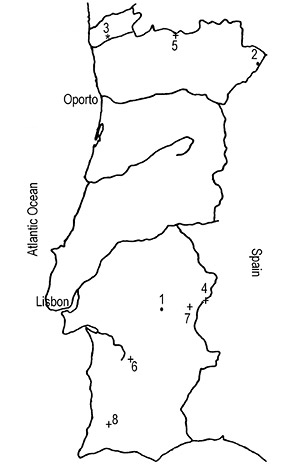

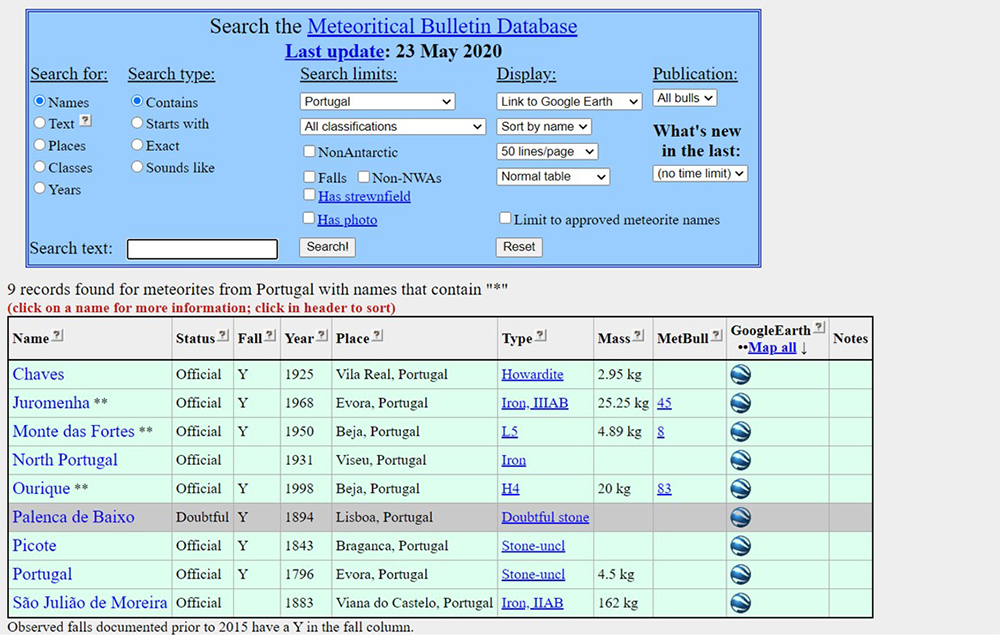

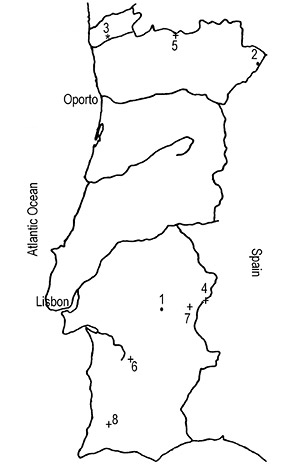

Quanto a Portugal, estão catalogados neste livro seis quedas e três achados. Mas é fácil detectar aqui algumas discrepâncias. Vejamos os casos claros, por ordem cronológica. Neste catálogo, estão listados o já citado Portugal (1796), e depois o Picote (1843, perto de Miranda do Douro), o São João de Moreira (achado em 1877, perto de Ponte de Lima), o Palença de Baixo (1894), o Chaves (1925), o Monte das Fortes (1950, perto de Santiago do Cacém), o Juromenha e o Ourique (a que voltaremos mais adiante). O nono é o misterioso “North Portugal”, que é descrito como um meteorito metálico que terá sido achado em 1931… algures (a referência a Viseu é dúbia). Mas sobre o Palença de Baixo fica um aviso: a de que não será provavelmente um verdadeiro meteorito.

Uma outra lista de meteoritos portugueses é dada num antigo Tema do Mês, aqui neste mesmo Portal do Astrónomo. J. Fernando Monteiro foi um geólogo português que se dedicou ao tema, e que realizou importantes estudos nesse âmbito. Infelizmente desaparecido em 2005, era também colaborador do NUCLIO, e foi dele a autoria do Tema de Outubro de 2004, dedicado aos meteoritos.

Neste trabalho são referidos oito meteoritos, mas em vez do “North Portugal” é referida uma queda em 1924, acontecida perto de Olivença, em que vários fragmentos caíram em Portugal (não vamos aqui discutir o estatuto daquela povoação). No Catálogo do Natural History Museum, este meteorito está ausente da lista referente a Portugal.

Há ainda referência ao caso ocorrido em 1884, em Palença de Baixo – mas em que não há qualquer evidência de que um meteorito tenha chegado à Terra. Além disso, a data indicada difere em 10 anos da dada no catálogo de Londres.

A quem quiser saber mais sobre a história destes meteoritos portugueses, recomenda-se a leitura do capítulo Pedras do Céu do Tema do Mês de Outubro de 2004, em que são referidas circunstâncias, amostras e estudos realizados.

Quanto à queda de 1968, em Juromenha (o meteorito também é conhecido como Alandroal), há algumas peripécias que justificam um pouco mais de atenção. O meteorito, caído numa zona fronteiriça de um país sob um regime ditatorial e numa época em que havia uma feroz competição entre os EUA e a URSS pela supremacia espacial, ficou nas mãos da Guarda Fiscal; e diz a lenda que foi colocado numa cela do posto local (prática que não era virgem; noutros tempos, as pedras que vinham do céu eram ciosamente guardadas, por vezes em celas, por se temer que voltassem sem aviso ao seu lugar de origem), antes de, através da GNR, ir parar às mãos do professor Carlos Teixeira, da Universidade de Lisboa, que se movimentou nesse sentido. Mais tarde, o meteorito foi “apanhado” no incêndio de 1978, que destruiu as instalações da dita instituição, em pleno centro de Lisboa, e foi recuperado do meio dos escombros.

Hoje, o meteorito está onde deve estar, na colecção do MUHNAC. É uma massa metálica de quase 24 kg, com uma face suave em que avultam os regmagliptos, ondulações provocadas pela passagem através da atmosfera, e outra mais rugosa e com pequenas ranhuras. Foi analisado há bastante tempo, mas o facto de ter sido afectado por um incêndio que atingiu elevadas temperaturas poderá ter tido alguma influência na sua estrutura – porém, não foram feitas análises em tempos mais recentes. Está classificado como um siderito do grupo IIIAB, mas com características únicas, que podem indicar que se trata de um representante de outro grupo ainda não individualizado. O meteorito, ou melhor, réplicas do mesmo, pode ser apreciado em exposições em diversos locais (no próprio MUHNAC, e nos Centros Ciência Viva de Constância e Lousal).

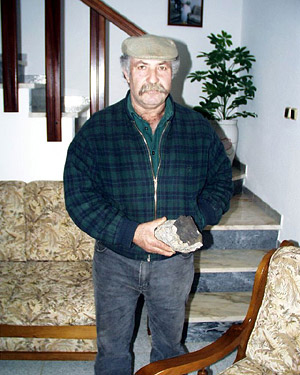

Em 1998, deu-se nova queda, na zona de Ourique, também no Alentejo. J. Fernando Monteiro assumiu um papel relevante na recolha e estudo deste meteorito, trabalho esse que deu origem à publicação de um fascículo, além da integração no inventário internacional com a respectiva classificação como condrito. Mais uma vez, recomenda-se a leitura do texto de J. Fernando Monteiro já referido, ou do fascículo publicado pela Univ. Lisboa e pela Câmara Municipal de Ourique.

Desde essa altura, tem havido observações esporádicas com relatos de eventuais meteoritos – mas nenhuma descoberta anunciada e comprovada. Há uns anos, recebi uma comunicação de uma eventual queda, testemunhada junto a Benavente. Desloquei-me ao local, mas para encontrar um vasto campo agrícola quase completamente inundado, que frustrou qualquer hipótese de conduzir uma busca por uma pedra de dimensões reduzidas.

No entanto, há por certo mais meteoritos espalhados pelo país. Por essa razão, fica aqui um apelo: se tem na sua posse, ou se há na sua escola ou outra instituição uma pedra que seja tida geralmente como um meteorito, conte-nos a sua história, e envie-nos uma fotografia e um resumo das suas características e dimensões, se possível. Gostávamos de poder construir uma lista de “candidatos” a meteoritos que possa ter um dia utilidade para quem os queira e possa estudar. Quem sabe que mistérios poderão ajudar a elucidar?

Uma última palavra para duas investigadoras portuguesas que fizeram carreira no exterior e que trabalham com meteoritos: Vera Fernandes, especialista em meteoritos lunares, que já esteve na Antártida à procura dessas pequenas rochas, e Zita Martins, astrobióloga de renome, actualmente no Instituto Superior Técnico. Não hesite em tentar contactá-las, se achar que tem de facto um meteorito interessante entre mãos.

Para concluir, aqui fica o endereço para onde poderão ser enviados dados sobre presumíveis meteoritos: nuclioMeteor@gmail.com.

Agradecemos desde já todas as contribuições.

Meteorites: pieces of the sky

As it travels through space, the Earth “collects” more than 100 tons of material each day. Of all that, only a small part is found and studied. Still, it was those rocky fragments, the meteorites, that gave us our first glimpses into the composition of the extra-terrestrial objects that we discovered, and of the story of the Solar System. What are they, where do they come from, where and how can they be found, and how do we go about studying them – these are some of the questions that we will explore in the next weeks of May.

Author: José Saraiva

José Saraiva trained as a geologist. He got a degree from the Univ. of Coimbra, and then an M. Sc. from IST (Technical University of Lisbon), where he spent long years as a project researcher. Mars and other planets, through the lens of Image Analysis, were the target of several researches during those years. Currently, he is a Project Coordinator at NUCLIO, after many years of collaboration.

⬇︎ Click below to read each part of this theme

Meteorites: pieces of the sky – Part 1

The Universe is very big. Even the Solar System, just a tiny corner of that Universe, is rather large. For us, human beings, but also for planets, even those, as Jupiter and Saturn, that we call giants. And so, it’s basically empty. However, they are out there: planets and dwarf planets, satellites, asteroids and comets, and so forth, to the smallest specks of interplanetary dust.

Since we, humans, like – or rather, need – to divide and classify stuff, group and pigeon-hole everything according to its nature, dimension, and so on, we also applied that principle to all that we have identified up there (or down there, or on the side – space is everywhere, wherever we turn to…)

And so we have those planets, dwarf planets, satellites… objects that have been going round in their paths since long ago, well behaved, far from the Earth, and that we do not expect to see crashing into our planet. (Though planetary orbits are ruled by chaos, when the very long time view is taken; and we have reasons to think that in the early days of the Solar System there may have occurred many crashes of that magnitude.)

And then we have asteroids and comets. Smaller objects, whose distributions are known to some degree, but that are too numerous – and so, though we know of the larger groups and their locations in the Solar System, they are far from being completely identified. These are possible visitors to our planet, and can lead to major effects, as we can see in some impact scars still visible on the surface of the Earth… and the disappearance of some groups of animals in the past (or so we think, at least).

However, we still have many more objects of small dimension, and those should not be called asteroids, of course… but we do need to find them a name, so: meteoroids. And it’s very easy to become entangled in this classification conundrum. How small is a meteoroid in the end? Let’s settle with the IAU classification: between 30 µm and 1 m. If it’s smaller… it’s a grain of dust. Still, the crucial thing is to understand that a meteoroid is an object that is travelling through interplanetary space.

What is the origin of meteorites? Let’s make a list: they can be pre-solar grains – after all, the matter that constitutes the Solar System did not just pop up from nothing; they can be grains coming from another system; they can be grains that condensed right at the beginning of the history of the Solar System, that were never integrated into larger objects; they can be grains that resulted from the processes that led to the formation of planets and other larger objects (meaning collisions); they can be grains resulting from later processes – random collisions between asteroids, passages of comets through the inner reaches of the Solar System, impacts on planets that led to the ejection of fragments into space; and, finally, they can be fragments of larger objects that came apart… if you have another idea, feel free to add it to the list. To sum it up, though, they are generally meteoroids or fragments of asteroids.

The next step is about their encounter with the Earth… A series of factors come into play: relative speed, angle of penetration into the atmosphere, nature of the object… and its size, of course. Since the Earth is a planet with a dense atmosphere, any object that crashes into it will meet resistance, drag… and suffer its consequences.

If the object under consideration is of small size, it will heat up and shine, and become visible in the (night) sky for a few moments, until it is “spent”. That happens at an altitude above 75 km, and it is a meteor, or shooting star. Sometimes these objects come in groups and produce “meteor showers”, normally related to comets, occurring when the Earth passes through a volume of space through which a comet went through, leaving a trail of particles.

Larger objects also suffer, obviously, heating for aerodynamical reasons, and they can reach the surface of the planet or be torn apart while crossing the atmosphere, spreading fragments whose speed is greatly reduced and that, while becoming meteorites, do not collide with enough speed to give origin to impact craters. That happens with even larger objects, though even those suffer some breaking up and produce a shower of fragments. In fact, though we may try to predict the behaviour of these objects, examples tell us that that is not straightforward.

Let us look at four relatively recent cases:

On 15 September 2007, there was news of an impact in Peru, near Lake Titicaca. The result was a crater with a diameter of around 15 m. The object must have been at least 3 m in diameter, but it was breaking up, and produced a meteor and a bang, and many small rocky fragments were recovered from the area. Some bizarre facts were linked to this impact. Local inhabitants that approached the crater shortly after the crash became ill, for reasons never completely clarified (probably because they inhaled sulphur compounds). A goat and a llama were found dead nearby. But the most curious was that, theoretically, this object should not have survived the passage through the atmosphere, and produce a crater. Calculations suggest that, though losing much of its speed, the crash must have happened at over 3 km/s.

On 7 October 2008, an object that had been identified a few hours before, approaching the Earth, exploded over the desert of Sudan. It was an asteroid, named 2008TC3, with a diameter of around 4 m, that penetrated the atmosphere at a speed of around 13 km/s and disintegrated at an altitude of 37 km, producing a rain (not a meteor shower, however!) of more than 600 meteorites, fragments, over the desert. Though the explosion produced a tremendous amount of energy, there occurred no damage, given the remote location and the high latitude of the event.

Let us move forward to 15 February 2013. A fireball was seen in broad daylight over the city of Chelyabinsk, in Russia. It was large and brighter than the Sun. The object responsible must have been larger than 20 m and penetrated the atmosphere at about 20 km/s, at a shallow angle. It didn’t survive, and exploded at an altitude of nearly 30 km. The shock wave produced damage in the Russian city, some kilometres away. In this case also, many fragments reached the surface of the Earth and became meteorites, though they failed to produce any significant craters.

And finally, just a few weeks ago, on 28 March 2020, a strange explosion shook a Nigerian town. Some early explanations pointed to a chemical explosion of human origin, but in the end, it was established that it had been a meteorite impact that created a crater with a diameter of 21 m. Though there are not many data about this impact, the culprit was probably an object of several metres, whose speed had been strongly reduced (witnesses claim to have seen it crashing down) and in the process of breaking up, that left, other than the crater, several fragments that will surely be studied in the future.

What can we conclude? That there are rocky fragments that come from space and reach the surface of the Earth, but not all of them produce impact craters, because of their size (we didn’t even mention micrometeorites, that we can picture “floating” slowly to the surface) or the circumstances surrounding the final moments of their long journeys. All of them are meteorites, something that is easy to recognise nowadays. However, it was not always like this.

Meteorites: pieces of the sky – Part 2

At the beginning of the 18th century, Isaac Newton declared that interplanetary space was, by necessity, empty. Such a statement, by Newton, could only mean that all the stories about rocks falling from the sky were in fact old wives’ tales, that came from the imagination and credulity of an ignorant people… or that those rocks had in fact an origin on the Earth. Because there was indeed no shortage of stories of that kind.

In western Antiquity, there are many narratives about falling meteorites, more or less mytified. The world was seen in a very different way, and the gods could do anything – ad they were prone to toying around with Humanity. At the time, no one knew that some primitive peoples used meteoritic iron to produce metal tools. Or that, inside Tutankhamon’s tomb, there was a dagger made from that same material that had come from afar.

And for a long time, there was also no word of the fact that, on the evening of 19 May of 861, in Japan, one of those stones coming from somewhere far off – from the sky, in fact – fell on the garden of a temple. The Japanese are, among other things, big on making boxes, and have a thing about permanence. Thus, the meteorite was kept by the monks in a little box, and there it stayed… for more than a thousand years. Until, in the 20th century, the story was rediscovered and talked about, and the rock was studied an identified as a meteorite. The oldest whose fall was registered and is still in existence.

Meanwhile, in Europe, a lot had changed. In 1492 (on 7 November) another meteorite fell, this one in Alsace, near the town of Ensisheim. There were witnesses, the stone was collected (and broken in many pieces – a large mass of 56 kg, less than half of the original, survived). The event was, of course, interpreted as a signal for the result of battles, a popular sport at the time in that “lively” area of Europe…Given that the press had been invented recently, the phenomenon was announced in pamphlets and used for propaganda purposes. As for the origin and nature of the object, that hardly mattered, really. It was just the will of another god.

It was only by the end of the 18th century that a number of falls were observed and recorded throughout Europe, and gave rise to an animated debate. Another fall in Italy, in 1766, led to the publishing of a book with a scientific explanation for the event: it was a rock launched into the sky by a volcanic eruption. Others could not agree, and put forth another hypothesis: it was a lightning bolt that launched the rock. In 1789, Lavoisier supported the old idea that such rocks could form (or aggregate) within the atmosphere. (Had he lost his head? Not yet, at the time…)

However, in 1794, Chladni, a German physicist (well known for his work in Acoustics), published a book about some iron masses found in different places, and proposed that they had an extra-terrestrial origin – and did his best to demolish all other explanations. Thus, the science of meteoritics was born.

One year later, a large meteorite fell in England, and in 1796 the first book on meteorites in English. In France, it took a real shower of almost 3000 meteorite fragments in 1803 to convince the scientific community of the reality of stones falling from the sky.

Nevertheless, the most widely accepted explanations continued to be atmospheric accretion and volcanic origin (except now coming from the Moon!)… until, that is, asteroids started to be discovered (from 1801 onwards). By the middle of the 19th century, the fact that meteorites were extra-terrestrial was firmly established. The discussion turned to finding out if they came from the asteroids, or from interstellar space – and it was only settled when the orbits of many objects could be analysed from records made by automated cameras. Nowadays, meteorites are recognised as cosmological, astronomical, physical, geological, chemical, mineralogical and meteorological objects (something first said in 1858). And as privileged witnesses of the history of the Solar System.

This rather shortened version of a fascinating story, full of ups and downs, does have yet another angle. Much of the knowledge about meteorites came from studying samples that were brought together in collections that are important to this day, in museums in Vienna, Berlin, London, Paris, and also in Russia and the USA. In there, samples from very famous meteorites can be seen.

The Natural History Museum of Vienna has one of the oldest and most extraordinary meteorite collections. The building itself is worth a visit, but really, for those who enjoy this subject, it’s the meteorites that shine brightest.

The images will do the talking.

Expeditions are still organised on a regular basis by some countries to collect meteorites. There are some places on the surface of the Earth where they can be more easily identified – the deserts. Mostly on icy ones – thus, Antarctica is regularly visited by those expeditions, given that dark rocks tend to be easy to locate on an ice field. The logistics for these adventures is rather complicated, of course. In sandy/rocky deserts, rocks are more common, but desert varnish can be very hard to distinguish from the fusion crust present in many meteorites…

There is still one question: are meteorites all alike? No. Not at all. As we shall see.

Meteorites: pieces of the sky – Part 3

Everybody knows that all meteorites are magnetic. All of them? No. Some still resist, now and always, to the magnet that tries to hold on to them (yes, that is a reference to Asterix)… Besides, some earthly rocks are magnetic too. Seems we just fell out of the blue into a discussion about meteorite composition… It’s probably better to start at the beginning.

To begin with, a primary division that has nothing to do with composition, and is concerned only with the circumstances of the identification: a meteorite can be seen falling to the ground – a “fall” – or be collected from the ground after the fact – in which case it is a “find”.

Let’s move on to more important things. Many people are convinced that meteorites are pieces of iron. No. There are in fact metal-rich meteorites, but there are others that are stony, apparently similar to many of the rocks that you can kick around (though not to all; there are no meteorites made of limestone or granite). And then there are those that are a mix of metal and rock. So, why do so many people think of iron when considering meteorites? Finding a piece of metal on the ground while taking a stroll is less common (even if you do it with a metal detector on your hand) than kicking another rock (don’t do it, there might be someone at the end of the path!) – thus, that piece of metal will attract much more attention, and it may even turn out to be an actual meteorite (though sometimes it will only be a piece of slag from some pre-historic foundry)!

That is why metal meteorites, known as irons or, more correctly, siderites, are more numerous in the existing collections. However, among those collected right after they fall to Earth, they represent less than 10%!!! And now, that there are regular campaigns to collect meteorites in far-off places, the numbers of other types of meteorites are on the rise in those collections. These other types are stony and stony-irons. We’ll get to those soon.

First, let’s consider the irons. They are dense (“heavy”), since… well, they are made of iron (and nickel) – and that also explains their magnetic nature. The nickel content and the relation between two iron and nickel minerals leads to the definition of diverse classes. An ancient classification that was based on the crystalline structure of those minerals is no longer applied.

Where can we find such pieces of metal with no rock? In the deep interior of planets such as the Earth – ok, we do not see it directly in our planet, because getting to the core of the Earth is only possible in Hollywood, but we know that the Earth (globally) is rather denser than the rocks we see on its surface, so… there must be some denser stuff at the bottom. And magnetic too. This seems like circular reasoning, but there are sound reasons for it. And in a couple of years there will be a space mission to a metal asteroid, Psyche, that will probably give us new insights into this matter, as we think that this asteroid was, at some point, the core of a protoplanet.

This object didn’t just pop up out of nowhere. It grew, incorporating smaller bodies, until it became big and hot enough to differentiate – the less dense materials (rocks) floated up (as silicate magmas), the denser (metals) flow to the interior. Since we now see a metal asteroid, we can ask where did the rocks go? They are around, probably scattered by a collision, and some became meteorites. They and others in the same group were once part of a protoplanet-size object, so they were involved in more or less complex geological processes, and they formed by cooling of silicate melts of diverse composition and age. That means they are basically magmatic rocks, similar to terrestrial rocks of the same origin, but enriched in metals (which is why they are magnetic).

This is also valid for Lunar or Martian meteorites, though these are missing in metals (given that Mars and the Moon are much larger and more differentiated than the asteroids or proto-planets) – thus, these highly-valued rocks (both in scientific and economic terms) have a much lower magnetic susceptibility.

Confused? Let’s see again: there are metal meteorites (irons, or siderites), and stony meteorites – rocks, or achondrites. But there’s more. There are stony meteorites that have never been involved in processes that led to large alterations of their original composition (melting, magmatic segregation). These are called chondrites, and there’s several types of them. They are, in fact, the most numerous type of meteorite falling to the Earth.

Where does this name come from? From the fact that they contain chondrules, small round granules of very old material. In fact, when they were analysed, chondrites revealed a global composition very similar to the Sun (minus hydrogen and helium), and that is a reason to consider that they represent chemically the primitive cloud that the planets grew from. Among them, there is a group called carbonaceous chondrites that is seen as the most primitive. In truth, it’s hard to say that we have really pristine meteorites, that are precisely as they were after matter condensed and accreted from the original cloud – even the oldest chondrites seem to show the passage of fluids (such as water).

So, we have irons and rocks (we’re not going into a detailed exploration of the many subgroups, that would be the stuff of another Theme of the Month; let’s just say that the particularities of composition and texture allow for a division into many classes, in both cases). But we do have another large and intermediate group of meteorites: those where stone and iron are both present, sometimes really mixed.

There are two subgroups that matter: pallasites (nothing to do with the asteroid Pallas!), probably the most beautiful of all meteorites, that show olivine crystals scattered in an iron mass; and the mesosiderites, or breccias, in which the two components are really mingled – it is thought that this type of meteorites results from violent collisions between asteroids.

Other than that, Lunar meteorites and the SNCs, the Martian meteorites, while being achondrites, have their own separate grouping, which is justified (and, of course, they are not all alike).

Is that all? Yes and no. This global survey of meteorite types is, on purpose, poor in detail; there are groups with only a few, or even only one example, which shows the amazing diversity of meteorites.

And there’s always the possibility that today, or tomorrow, a different, new type of meteorite will crash to the Earth – maybe it has already made landfall: there are stories about meteorites with organic matter (which are true), and of others that brought some strange “microorganisms” (still debated).

To conclude: we don’t know everything, we will never know everything. You don’t classify meteorites by looking at a hand sample. To study meteorites, we use the methods that are applied to the study of other rocks: microscopy, chemical and isotopic analysis. The results of those observations provide the basis for the many classes that have been defined.

We should remember that it was studying meteorites (and their isotopic clocks) that led to the determination of the age of the Earth, 4550 million years (but that’s another story worthy of its own Theme). One thing is certain: there’s still a lot to discover and learn in the world of meteorites.

Meteorites: pieces of the sky – Part 4

Where are the meteorites that fell in Portugal? It’s not easy to find an answer to the question. There is no national collection. In the National Museum of Natural History and Science (MUHNAC) there are some meteorites, but there was a deliberate effort to gather references, locations and samples. There are some known meteorites, catalogued, and presently located in Universities and Museums, but there must surely be some unknown specimens here and there, in schools, local museums and private homes (in my grandmother’s house there was a nice fragment of metal that had a long and shady history… she hailed from Redondo, in Alentejo, but unfortunately the rock vanished long before I could reclaim it as a piece of peculiar interest).

Still, there are some stories that are worth sharing.

For instance: in 1786, on 19 February, a meteorite fell near Évora Monte. An official document was written, with the testimonies of those that observed the fall, and it was translated to English by Robert Southey, a name that carries some weight in English letters, and that was traveling through the country at the time. This meteorite is listed in the international data base, bearing the name ‘Portugal’, but there is no notice of the whereabouts of any of its fragments. This fall happened at the time when the attention given to the phenomenon was growing, and the ideas about its origin was changing.

On the other hand, there should be no doubts that, through the centuries of Portuguese colonial presence in Africa and South America, many falls must have been seen, some meteorites must have been found on the ground – yet, once again, finding references to those events would demand a tremendous research effort. Given that the recognition of the extra-terrestrial nature of meteorites only happened at the beginning of the 19th century, if we look for official numbers, or those meteorites that are catalogued (in Brady’s Catalogue of Meteorites, 5th Edition, published in 2000, or in the site of the Meteoritical Society), we can try to gather some data… though we won’t get far.

For Angola there are three records of ‘falls’, somewhat recent (1961, 1966, and 1974), and one ‘find’. There are no records for any of the other Portuguese-speaking countries (Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, Cape Verde and S. Tomé and Príncipe) – this is particularly weird for Mozambique, a rather large country. In the case of Brazil, numbers are larger, with 21 falls and 31 finds in record (Brazil became independent in the second decade of the 19th century, so they all belong to the post-colonial period).

As for Portugal, we have in this book six falls and three finds. There are, however, some discrepancies. In this catalogue, and in chronological order, we have the following: the already mentioned Portugal (1796), and then Picote (1843, near Miranda do Douro), São João de Moreira (found in 1877, near Ponte de Lima), Palença de Baixo (1894), Chaves (1925), Monte das Fortes (1950, near Santiago do Cacém), Juromenha and Ourique (to which we will return). The ninth is a mysterious ‘North Portugal’, described as a metal meteorite found in 1931… somewhere (the reference to Viseu is dubious). And about Palença de Baixo there is a warning that it probably is not a true meteorite.

Another listing of Portuguese meteorites is given in an old Theme of the Month, published here at the Portal do Astrónomo. J. Fernando Monteiro was a Portuguese geologist that worked in this field, and that made important contributions to it. Unfortunately, he passed away in 2005; he was a collaborator of NUCLIO, and he was the author of the Theme of the Month for October 2004 (only in Portuguese), dedicated to meteorites.

There are also eight meteorites mentioned in this work, but instead of ‘North Portugal’ we have a fall in 1924 that happened near Olivenza, with several fragments finding their way to the Portuguese side of the border (we will not discuss the legal standing of the town). On the Natural History Museum, this meteorite is not included in the Portuguese list.

There is a further reference, to the event at Palença de Baixo, but in this case there is no evidence that a meteorite fell to Earth. And the date is 10 years off relative to the one given in the London Catalogue.

Anyone wishing to learn more about the history of these Portuguese meteorites should read the Pedras do Céu (Stones from the sky) chapter of the Theme of the Month for October 2004, in which are presented accounts of the events, samples and studies conducted (only in Portuguese, though).

The fall of 1968, in Juromenha (this meteorite is also known as Alandroal), there are some details that call for a little more attention. The meteorite fell in a border region of a country ruled by a dictatorial regime, at a time when there was a fierce competition between the USA and the USSR for dominance in space, and so it naturally ended in the hands of the Border Patrol; according to legend, it was kept in a cell at the local station (which was not a new thing; in older days, stones falling from the sky were jealously guarded, sometimes in cells, for fear that they would return with no warning to their place of origin), before finding its way, under the authority of another police force, into the hands of Carlos Teixeira, a professor from the Lisbon University, that had worked for that purpose. Later, the meteorite was caught in a fire that broke out in 1978 and destroyed the facilities of the University, in a central area of the town, and was later recovered from the rubble.

Today, the meteorite is in its right place, in the MUHNAC collection. It’s a dark metal mass, weighing almost 24 kg, with a soft face with regmaglypts, wavy shapes that result from the high-speed crossing of the atmosphere, and another face, rougher and with some grooves. It was analysed after the fall, but the fact that it was caught in a blaze that reached high temperatures can have caused some alterations in its structure – however, there are no newer analyses. It has been classified as a siderite, group IIIAB, but it possesses some unique characteristics that may indicate that it is in fact a representative of another group not yet created. The meteorite, or rather its replicas, can be seen in several locations (at the MUHNAC, or at the Ciência Viva Centres of Constância and Lousal).

In 1998 there was another fall, near Ourique, also in Alentejo. J. Fernando Monteiro played a relevant role in the collection and study of this meteorite, and that work led to the publication of a booklet, other than the integration in the international inventory, with a classification of chondrite. Once more, we recommend reading the already mentioned text by Monteiro, or seeking out the booket published by the Lisbon University and the Ourique Municipality.

Since then, there have been sporadic observations with stories about possible meteorites – but no discovery announced and confirmed. Some years ago, we received news of a fall, seen near Benavente. Travelling to the area, we found a large field almost completely flooded, that frustrated any idea of looking for a smallish stone.

Still, there are surely more meteorites around the country. And that is why we are sending out an appeal: if you have possession, or know of the presence in your school or other institution, of a rock that is thought of as a meteorite, tell us its story, and send us an image and a list of its characteristics and dimensions, if possible. We would like to create a list of meteorite ‘candidates’ that may one day help anyone willing and able to study them. Who knows what mysteries they can help to elucidate?

A final word about two Portuguese researchers that have made a career abroad working with meteorites: Vera Fernandes, an expert on lunar meteorites that has been to Antarctica looking for those little rocks, and Zita Martins, a well-known astrobiologist, presently at the University of Lisbon. Do not hesitate in reaching out to them if you think you do have an interesting meteorite in your hands.

To conclude, here’s the address where you can send your data on would-be meteorites: nuclioMeteor@gmail.com.

We thank you for all contributions.

Leave a Reply