Celebrar a Matemática

Este tema está dividido em 4 partes:

Parte 1 – Parte 2 – Parte 3 – Parte 4

For English version click here

Celebrar a Matemática – Parte 4

Toda a parte na matemática

Ao longo deste mês propusemo-nos Celebrar a Matemática na rubrica Tema do Mês do Portal do Astrónomo. Começámos por destacar o Dia Internacional da Matemática (DIM) que decorreu, pela primeira vez, a 14 de março de 2020, subordinado ao tema a matemática está em toda a parte. Para memórias futuras, o vídeo coletivo, para o qual contribuíram pessoas de diversos locais do globo, sugere a diversidade de culturas e de contextos em que a matemática está presente, o espírito de colaboração e como o domínio da linguagem formal da matemática permite comunicar e também unir pessoas.

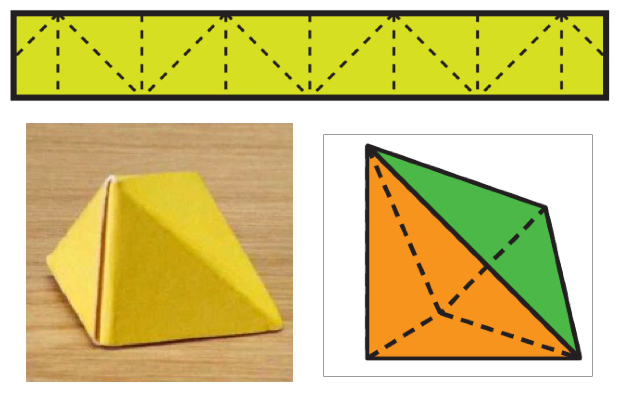

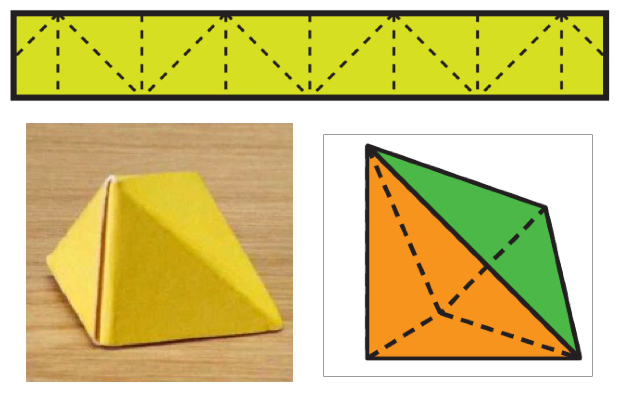

Posteriormente, já depois das muito tímidas celebrações do DIM no atual contexto de pandemia, foi sugerida uma visão da matemática como ciência dos padrões, com base na metodologia da investigação matemática, e também do papel de especialistas que trabalham com e/ou desenvolvem a matemática – cientistas, educadores, comunicadores – como indivíduos que tornam visível a parte oculta ou menos explícita da matemática “aos olhos” de outros. Aliámos a estes ingredientes uma componente cultural, com o exemplo de identificação de padrões e frisos matemáticos em objetos oriundos de culturas distintas, destacando uma conceção de matemática viva, dinâmica, cultural e humana.

Na sequência deste tema, e para fechar este ciclo de celebração da matemática, inspiramo-nos em alguns trabalhos desenvolvidos em contextos africanos, abordagens com preocupações matemáticas, antropológicas, políticas e sociais que desocultam a matemática embutida em práticas culturais. Finalmente, propomos um exercício de inclusão, no sentido de evidenciar que toda a parte está na matemática.

Elementos culturais como azulejos, a calçada portuguesa ou tecidos africanos têm presentes diversas simetrias (ver parte 3). Essa matemática torna-se visível na análise do produto final, mas se pensarmos na produção e confeção desses mesmos elementos, nas técnicas utilizadas, podem colocar-se outras questões:

Por exemplo, uma variedade de tipos de simetria é usada para decoração em todas as culturas, numerosas construções são feitas ilustrando leis matemáticas. Em que medida são estas actividades realmente “matemáticas”? O que é isso que faz as actividades “matemáticas” …?

(Howson et al., 1985, p. 15 citado por Gerdes, 2012a, p.63)

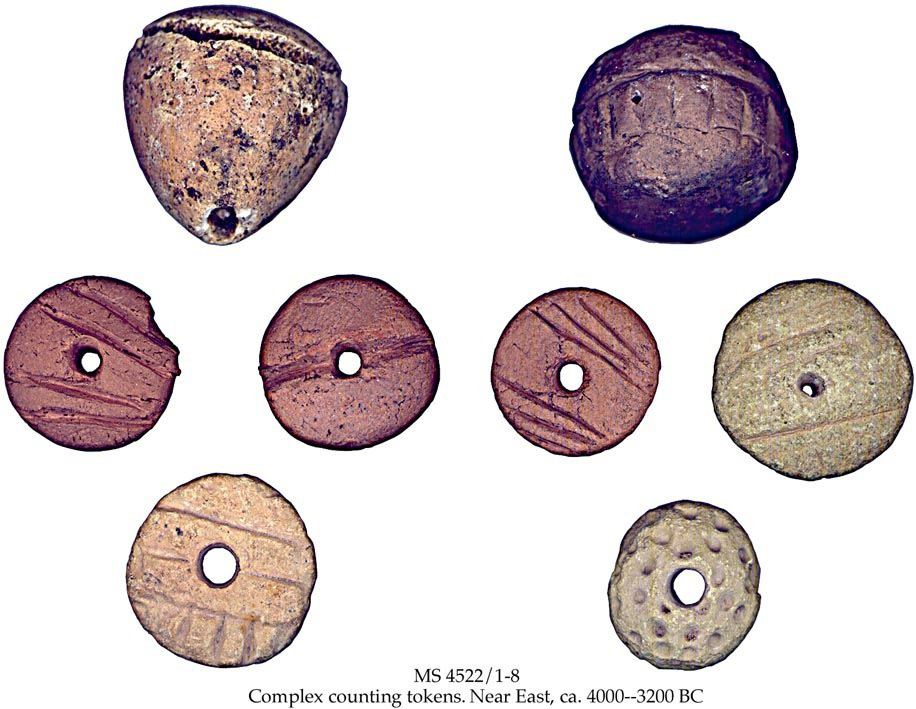

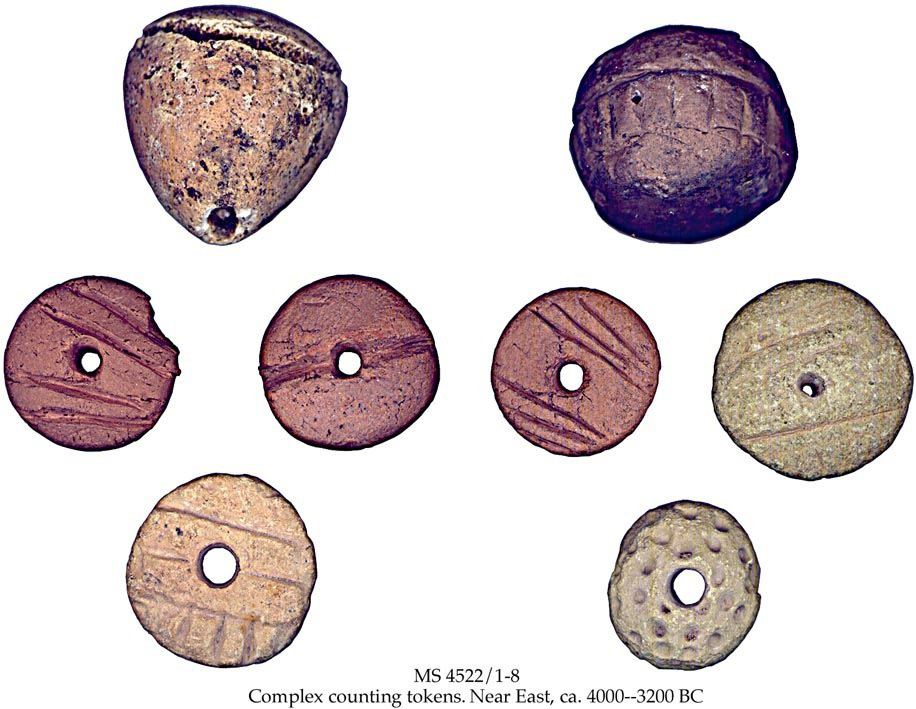

Transversalmente a culturas por todo o mundo, é possível identificar o desenvolvimento de algumas atividades envolvendo ideias matemáticas como contar, medir, explicar, localizar, desenhar e jogar [1]. Por exemplo, os sistemas de numeração – alguns têm registos escritos, em outros casos a informação é transmitida oralmente de geração para geração; traços, nós, pedras, paus são por vezes utilizados como auxiliares de contagem, as bases numéricas são muito distintas, mas, de uma forma ou de outra, a contagem faz parte de cada cultura [2, 3].

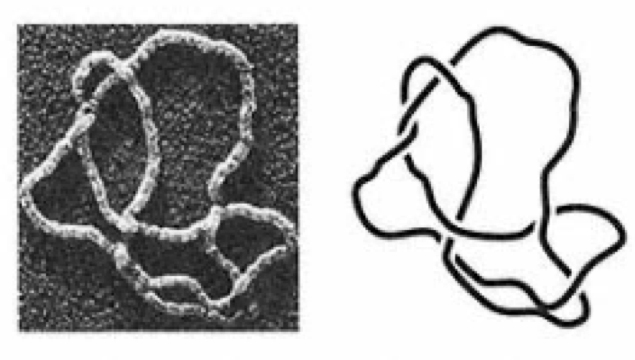

A evolução do registo escrito, de culturas e conhecimentos dominantes em determinadas regiões do globo fizeram com que muito desse conhecimento matemático tenha ficado implícito, escondido, ocultado, congelado, oprimido, invisível em práticas culturais.

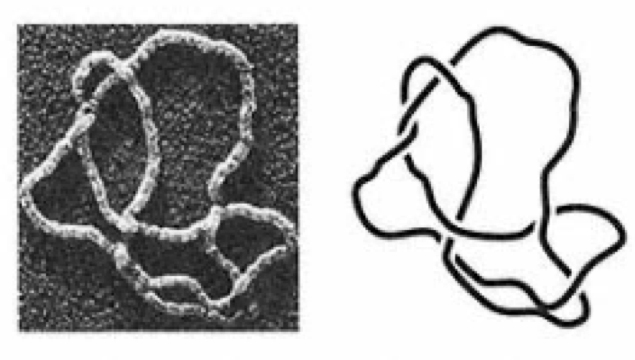

Matemátic@s, antropólog@s e outr@s investigador@s com preocupações sociais e políticas têm analisado e interpretado representações de ideias matemáticas pela análise de práticas culturais. Por exemplo, Marcia Ascher menciona ideias matemáticas de pessoas indígenas – indigenous people no original – para referir a matemática desenvolvida e praticada em culturas e comunidades de pequena escala e distantes dos focos de cultura dominante [4]. O termo descongelar a matemática, utilizado por Paulus Gerdes no contexto de Moçambique, surge associado a uma olhar para práticas e instrumentos culturais que desoculta e (re)faz emergir pensamentos e ideias matemáticas que foram escondidos ou oprimidos durante a época colonial [3, 5]. Já Claudia Zaslavsky opta pelos termos explícita e implícita para se referir a uma representação da matemática registada formalmente nos livros, ou a representações de ideias e práticas produzidas utilizando pensamento matemático para suprir necessidades ou interesses das sociedades, respetivamente [2].

Nas práticas culturais, a matemática surge predominantemente contextualizada e com significado para quem a pratica, digamos que se trata de uma dimensão local da matemática. As interpretações e representações de ideias matemáticas desenvolvidas em determinados contextos culturais, e que se designam por etnomatemáticas, consistem na representação explícita da matemática a uma escala local.

No extremo oposto, e tendencialmente descontextualizada, a matemática formal enquanto linguagem universal permite a comunicação entre diferentes comunidades, ou seja, a matemática na sua dimensão global. Isto significa que, dependendo do contexto em estudo, assim é considerada a escala, local ou global, sendo igualmente possível serem trabalhadas conexões entre elas [6].

Na esfera educacional, esta conexão tem sido experimentada, especialmente, em contextos onde os currículos matemáticos ainda surgem associados a referências importadas, muitas vezes como “herança” de relações coloniais. Abordagens etnomatemáticas têm evidenciado o potencial matemático de cada alun@, não no sentido de cada um(a) poder vir a ser um(a) grande matemátic@, mas na medida em que cada indivíduo está apto para pensar matematicamente, desde que seja considerado como ponto de partida um referencial que lhe é familiar.

Em síntese…

Tornar o invisível, visível, corresponde à conversão entre as representações implícita e explícita da matemática. Consideremos estas representações ao longo de um continuum entre a dimensão local e a dimensão global da matemática.

A visão de Devlin (ver parte 3 deste Tema do Mês) ou alguns dos exemplos apresentados no vídeo coletivo do DIM enquadram-se na matemática a uma escala global, uma vez que utilizam contextos em que a matemática é utilizada, de forma mais ou menos consciente, por não profissionais desta área (artistas, arquitetos, engenheiros, etc.) para evidenciar a matemática enquanto linguagem universal.

Todas as culturas desenvolvem ideias matemáticas, todas as pessoas contam, todos os indivíduos apresentam um potencial matemático a explorar. Com uma “lente” explícita ou implícita, a uma escala global ou local, celebrar a matemática em todas as suas formas é reconhecer a diversidade, é incentivar práticas inclusivas, é contribuir para que qualquer pessoa se sinta também parte… da matemática.

Sugestões de leitura complementares:

[1] Bishop, A. (1988). Mathematical enculturation: a cultural perspective on mathematics education. Dordrecht: Kluwer. [2] Zaslavsky, C. (1994). Mathematics in África: Explicit and implicit. Em I. Grattan-Guinness (Ed.). Companion Encyclopedia of the History and Phylosophy of the Matematicals Sciences: Vol1 (pp. 85-92). Londres: Routledge. [3] Gerdes, P. (2012a). Etnomatemática – Cultura, Matemática, Educação: Colectânea de Textos 1979-1991 (reedição). Boane: Instituto Superior de Tecnologias e Gestão. [4] Ascher, M. (2002). Mathematics Elsewhere. An exploration of ideas across cultures. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [5] Gerdes, P. (2012b). Otthava: Fazer Cestos e Geometria na Cultura Makhuwa do Nordeste de Moçambique (reedição). Boane: Instituto Superior de Tecnologias e Gestão. [6] Latas, J. & Moreira, D. (2013). Explorar conexões entre matemática local e matemática global. Revista Latinoamericana de Etnomatemática, 6(3), 36-66.

ENGLISH VERSION

This theme has four parts

Part 1 – Part 2 – Part 3 – Part 4

Celebrating Mathematics – Part 4

All parts in mathematics

Our aim for this series was to Celebrate Mathematics in the Theme of the Month section of Portal do Astrónomo. We began by highlighting the International Day of Mathematics (IDM) that was for the first time ever celebrated on 14 March, with the theme mathematics is everywhere. For future memory, the collective video, to which people from around the world contributed, suggests the diversity of cultures and contexts in which mathematics is present, praises a collaborative spirit and shows how dominating the formal language of mathematics allows for communicating and bringing people together.

Later, after the timid celebrations of the IDM, understandable in the current pandemic situation, we suggested a vision of mathematics as the science of patterns, based on the methodology of mathematical research, and also on the role played by experts that work with and/or develop mathematics – scientists, educators, communicators – as people that make visible the hidden or less explicit part of mathematics “in the eyes” of others. To those ingredients, we added a cultural component, with the example of the identification of mathematical patterns and friezes in objects originating in diverse cultures, pointing to a conception of mathematics that is alive, dynamic, cultural and human.

Continuing in this theme, and to conclude this cycle of celebration of mathematics, we found inspiration in some works developed in an African context, approaches with mathematical, anthropological, political and social concerns that unveil the mathematics embedded in cultural practices. Finally, we propose an inclusion exercise, to make clear that all parts are in mathematics.

Cultural elements such as tiles, Portuguese traditional sidewalks or African fabrics incorporate different symmetries (see part 3). Mathematics becomes visible when we analyse the final product, but if we think about the production and manufacture of those elements, and in the techniques employed, other questions may come to mind:

For instance, a variety of types of symmetry is used for decorative purposes in all cultures, and many buildings are put up in a way that illustrate mathematical laws. To what measure are these activities really “mathematical”? What is it that makes them “mathematical”…?

(Howson et al., 1985, p. 15, quoted in Gerdes, 2012a, p.63)

Throughout the different cultures of the world, we can identify the development of some activities that involve mathematical ideas, such as counting, measuring, explaining, locating, drawing and playing [1]. For instance, numbering systems – some have written records, in other cases the information is orally transmitted from one generation to the next; dashes, knots, stones, sticks are sometimes used as auxiliary means to count something; numerical bases are distinct but, in one guise or another, counting is a part of every culture [2, 3].

The evolution of the written record, of cultures and knowledges that dominated certain areas of the globe, contributed to make a large part of that mathematical knowledge implicit, hidden, occult, frozen, oppressed, invisible in the cultural practices.

Mathematicians, anthropologists and other researchers with social and political concerns have analysed and interpreted representations of mathematical ideas through the analysis of cultural practices. Marcia Ascher, for instance, mentions the mathematical ideas of indigenous people to point out the mathematics that was developed and practiced in small scale cultures and communities, far from the centres of dominating cultures. The term thawing of mathematics, employed by Paulus Gerdes in the context of Mozambique, appears in association with a regard to cultural practices and instruments that unveils and brings (back) mathematical thoughts and ideas that have been hidden or oppressed during colonial times [3, 5]. On her side, Claudia Zaslavsky chooses the terms explicit and implicit to respectively talk about the representation of mathematics formally recorded in books, or about representations of ideas and practices produced using mathematical thought to supply needs or interests of societies [2].

In cultural practices, mathematics appears predominantly in context and is meaningful to those who practise it; let’s call it a local dimension of mathematics. Interpretations and representations of mathematical ideas developed in given cultural contexts, designated as etnomathematics, consist of the explicit representation of mathematics on a local scale.

On the other end of the spectrum, and tending to an existence out of context, formal mathematics as a universal language allows for the communication between different communities; in other words, mathematics in its global dimension. This means that, depending on the context under study, the scale is deemed local or global, and that the connections between them can be probed [6].

In the sphere of education, this connection has been tried out, especially in contexts where the mathematical curricula are still associated to imported references, often as an “heritage” from colonial relations. The ethnomathematical approaches have revealed the mathematical potential of each student, not in the sense of each one of them possessing the potential to become a great mathematician, but showing that each individual is able to think mathematically, as long as the starting point is something that is familiar to him/her.

To conclude…

Making the invisible visible corresponds to a conversion between the implicit and explicit representations of mathematics. Let’s consider these representations along a continuum between the local and global dimensions of mathematics.

Devlin’s vision (see part 3 of this Theme of the Month), or some of the examples presented in the collective video of the IDM, are framed in the global scale of mathematics, since they use contexts in which mathematics is employed, in a more or less conscious way, by professionals of other areas (artists, architects, engineers, etc.) to highlight mathematics as a universal language.

All cultures develop mathematical ideas, everyone counts things, all individuals hold a mathematical potential there to exploit. With an explicit or implicit “lens”, at a global or a local scale, celebrating mathematics in all its shapes and formats is to recognize diversity, to foster inclusive practices, to contribute to making each and everyone feel they are also part… of mathematics.

Leave a Reply