Celebrar a Matemática

Este tema está dividido em 4 partes:

Parte 1 – Parte 2 – Parte 3 – Parte 4

For English version click here

Celebrar a Matemática – Parte 3

Matemática, continuas aí?

Nota prévia:

Num exercício de autodisciplina, optei por esta semana evitar a tentação de escrever recorrendo a analogias, a análises numéricas ou estatísticas da propagação da COVID-19 ainda que o pensamento, os estímulos e as rotinas o tenham como central. Convido @ leitor(a) a fazer esse mesmo exercício e a ir buscar um pouco de tranquilidade, mesmo que momentânea, a outras ideias.

Ciência dos padrões é uma definição de matemática proposta por Keith Devlin e atualmente aceite por muit@s matemátic@s quando focamos o como se estuda/investiga/desenvolve a matemática [1], [2]. Realço “atualmente”, porque nem sempre assim foi e provavelmente deixará de o ser daqui a algum tempo. O dinamismo e relatividade da matemática fazem com que o próprio conceito evolua. Os padrões analisados pel@s matemátic@s podem ser referentes a contagem, forma ou comportamento, bem como visuais ou mentais, qualitativos ou quantitativos, estáticos ou dinâmicos. Por vezes, os padrões surgem do pensamento abstrato e são posteriormente aplicados à realidade, outras vezes, é a contemplação dos fenómenos reais que inspira os modelos. Podem, inclusive, inspirar formatos irreverentes, como em In flowers through space, uma recente interpretação musical da sucessão de Fibonacci [3].

Tornar o invisível, visível constitui assim um desafio para @s matemátic@s, educadores(as) matemátic@s ou comunicadores(as) de ciência. No entanto, este processo de desocultar a matemática pode ser feito em diferentes níveis de robustez e formalização, dependendo do objetivo pretendido e da própria conceção de matemática. Certamente que a robustez de linguagem que @ matemátic@ utiliza para comunicar entre pares não é eficiente numa situação de sala de aula, na comunicação entre @ professor(a) e @s seus alun@s, e não será a escolhida por um(a) comunicador(a) de ciência que pretenda promover um diálogo efetivo com públicos não especialistas. Além disso, tornar visível a matemática que mantém um avião no ar pela enunciação da equação de Bernoulli exige um nível de formalização distinto daquele que é requerido para associar a forma do telhado de uma casa a um prisma triangular.

Apesar de a matemática estar, por vezes, oculta aos olhos de muit@s, a cultura pode atuar como um estímulo ao proporcionar experiências que tornem visível, ao olhar de qualquer indivíduo da sociedade, a matemática implícita.

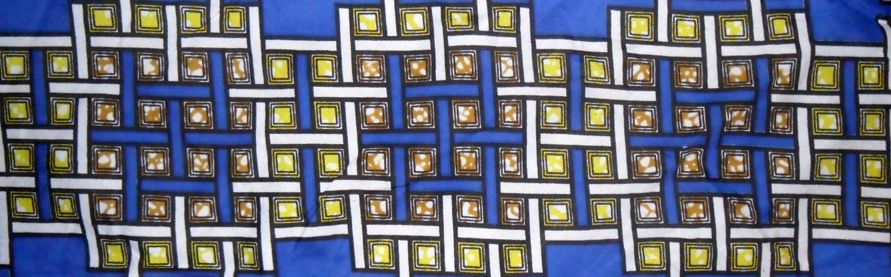

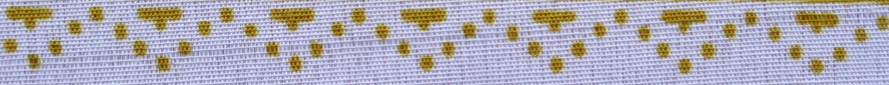

Washburn & Crowe [4] aplicaram a teoria dos grupos à análise dos padrões de repetição do plano presentes em tecidos, esculturas em madeira, cestaria e outros objetos pertencentes a diferentes culturas. Estudos sobre a calçada portuguesa ou os painéis de azulejos em algumas cidades portuguesas mostram também a utilização de uma grande diversidade de frisos e padrões; ainda que, até ao momento, não tenham sido identificados os 17 padrões matematicamente possíveis, quer na calçada, quer nos azulejos, e que haja tipos de padrões, mais simétricos, mais frequentes do que outros [5]. De uma maneira geral, os diferentes tipos de frisos e padrões são utilizados e (re)inventados em diferentes locais e culturas e, sem qualquer intuito de obedecerem a uma determinada tipologia, por vezes abarcam todas as possibilidades matemáticas, como é o caso dos sete frisos identificados na calçada portuguesa, nos azulejos nas cidades de Ovar e no Porto, ou em tecidos africanos. Isto evidencia uma faceta humana na matemática, como uma parte rica e viva da cultura.

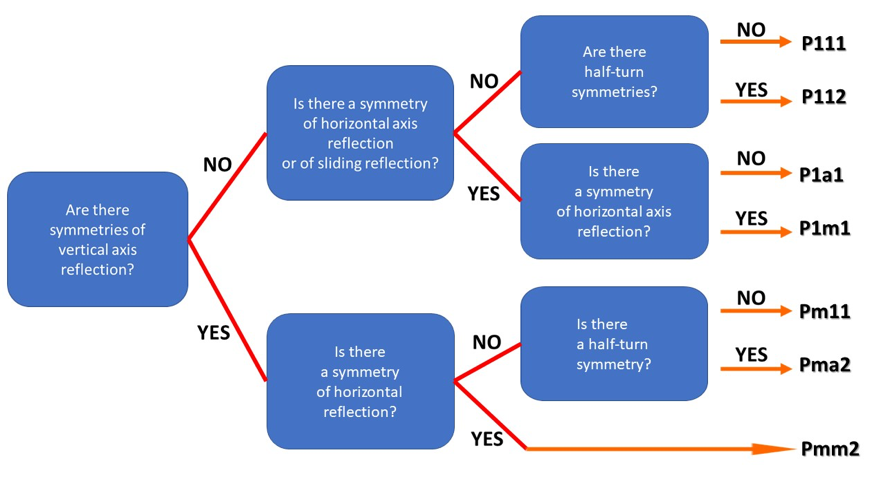

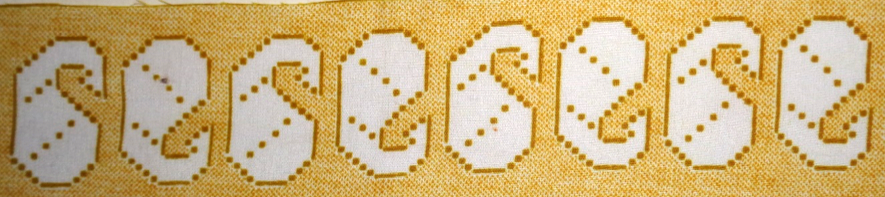

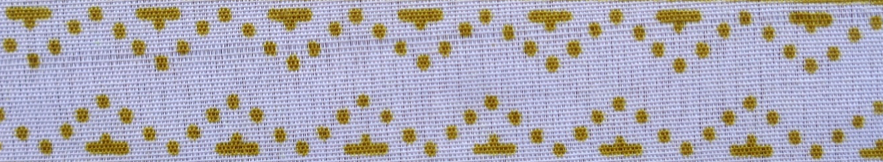

Desafio @ leitor(a) a um olhar matemático pelas seguintes imagens de recortes de tecidos africanos. São 7, tantas quantos os tipos de frisos que existem no plano. Cada uma das imagens corresponde a um tipo de friso (podendo haver ou outra imperfeição ou algum plano fotográfico que não seja o perfeito). Qual corresponde a qual?

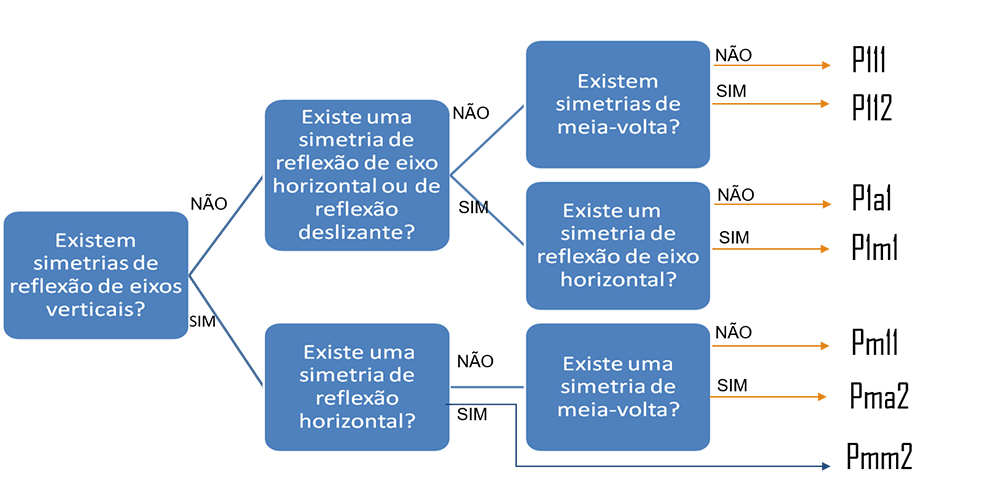

O seguinte esquema poderá ajudar a classificação de frisos:

O programa Gecla, produzido e distribuído gratuitamente pela Associação Atractor, poderá ser um bom suporte para este desafio, acrescido da componente tecnológica.

Sugestões de leitura complementares:

[1] Devlin, K. (2000). The language of mathematics: making the invisible visible. New York, NY: W. H. Freeman and Company. [2] Devlin, K. (2002). Matemática. A ciência dos padrões. Porto: Porto editora. [3] Ver também a este propósito o artigo Finonacci-Based music that is not a Fibonacci folly escrito por Keith Devlin. [4] Washburn, D. & Crowe, D. (1988). Symmetries of culture: Theory and practice of plane pattern analysis. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. [5] Ver, por exemplo, Matemáticas nas Calçadas de Lisboa e Rota das simetrias em Lisboa, Roteiros de simetria no arquipélago dos Açores, Matemática dos azulejos com recolha de dados nas cidades portuguesas de Ovar e Porto. [6] Veloso, E. (2012). Simetria e transformações geométricas. Lisboa: APM.

ENGLISH VERSION

This theme has four parts

Part 1 – Part 2 – Part 3 – Part 4

Celebrating Mathematics – Part 3

Mathematics, are you still there?

A previous note:

In an exercise of self-discipline, this week I’ve chosen to avoid the temptation of writing using analogies, numerical analyses or statistics about the propagation of COVID-19, even though our thoughts, stimuli and routines are all centred on that. I invite the reader to follow this example and to look for a bit of tranquility elsewhere, even if only for a brief moment.

The science of patterns is a definition of mathematics put forward by Keith Devlin, and currently accepted by many mathematicians, best applied when one is focused on how you study/research/develop mathematics [1], [2]. I highlight “currently”, because it was not always like this, and it will probably not be like this in the future. The dynamics and relativity of mathematics lead to an evolution of the concept. The patterns that mathematicians analyse can be related to counting, shape, or behaviour, they can be visual or mental, qualitative or quantitative, static or dynamic. Sometimes patterns emerge from abstract thinking and are applied to reality afterwards, in other instances it is the contemplation of real phenomena that inspires models. They can even inspire some irreverent formats, such as those in In flowers through space, a recent musical interpretation of Fibonacci’s sequence [3].

Making the invisible visible is thus a challenge for mathematicians, mathematical educators or science communicators. However, there can be different levels of robustness and formalisation for this process of unveiling mathematics, depending on the objectives to be achieved and even on the notion of mathematics that is used. Surely, the robustness of the language employed by a mathematician to communicate with his/her peers will not be efficient in classrooms, for the communication between teachers and their students, and will not be the choice of a science communicator intent on promoting a fruitful dialogue with the general public. Besides, making the mathematics that keeps a plane in the air visible by stating Bernoulli’s equation requires a level of formalism quite distinct from the one required to associate the shape of the roof of a house to a triangular prism.

Even though mathematics is often hidden from sight, culture can act as a stimulus by providing experiences that reveal the implicit mathematics to the eyes of any member of society.

Washburn & Crowe [4] applied group theory to the analysis of the patterns of plan repetition that occur in cloths, wooden sculptures, basket weaving and other objects from diverse cultures. Studies of the Portuguese “calçada” (the patterns on the sidewalk made with coloured stones) or of tile panels in some Portuguese cities also show the use of a large variety of friezes and patterns; it’s true that, at least so far, the 17 mathematically possible patterns have not all been identified either on the sidewalks or on tiles, and that there are some patterns, more symmetrical, used more often than others [5]. In general, the different types of friezes and patterns are used and (re)invented in diverse places and cultures and, with no intention of obeying a given typology, sometimes cover all mathematical possibilities, as in the case of the seven friezes identified on the Portuguese sidewalks, on the tiles of the cities of Ovar and Porto, or in African fabric. This reveals a human side to mathematics, a rich and living part of culture.

Here’s a challenge to the reader: cast a mathematical look at the following images of African fabric. There are seven, as many as the types of frieze present. Each of the images corresponds to a type of frieze (taking into account any imperfection or a less than ideal photograph). Which corresponds to what?

The following graph can be helpful for the classification of friezes:

The program Gecla (page in Portuguese), produced and freely distributed by Associação Atractor, can be a good support for this challenge, adding a technological component.

Leave a Reply