O que faz uma física de partículas?

❉ Este é o primeiro de uma série de artigos preparados pelas nossas colaboradoras da Soapbox Science Lisbon. Iremos publicá-los regularmente, começando pelos escritos pelas organizadoras e continuando com os das oradoras. Os artigos irão cobrir diferentes tópicos, tendo sempre como base a perspetiva das mulheres na ciência. Fiquem atentos para não perderem os próximos artigos. Este ano, a segunda edição do evento Soapbox Science Lisbon, para promover as mulheres na ciência, terá lugar no dia 23 de Outubro, por isso, guardem esta data!

O que faz uma física de partículas?

Por Márcia Quaresma

Desde muito nova, algures no 2º ciclo, decidi que gostava de seguir física quando fosse para a Universidade. Na altura, nem sequer sabia que existia uma área da física chamada física de partículas. O mais próximo da física de partículas que eu conhecia era talvez a física nuclear, que, acredito, a maioria das pessoas tem uma ideia do que seja. Mas e em relação à física de partículas, será que a população sabe do que se trata?

Quando cheguei à universidade, em 2005, logo numa das primeiras aulas que tive, o professor falou-nos imenso do CERN, que eu já tinha ouvido falar, mas aí sim, percebi a sua dimensão. Na altura poucas pessoas sabiam do que se tratava. Acredito que hoje, passados 16 anos, e após a muito noticiada descoberta do bosão de Higgs em 2012, mais e mais pessoas já saibam o que é o CERN. Este laboratório, na fronteira entre a França e a Suíça, é o maior da Europa, onde milhares de cientistas unem esforços para aprender mais sobre as partículas mais elementares que conhecemos.

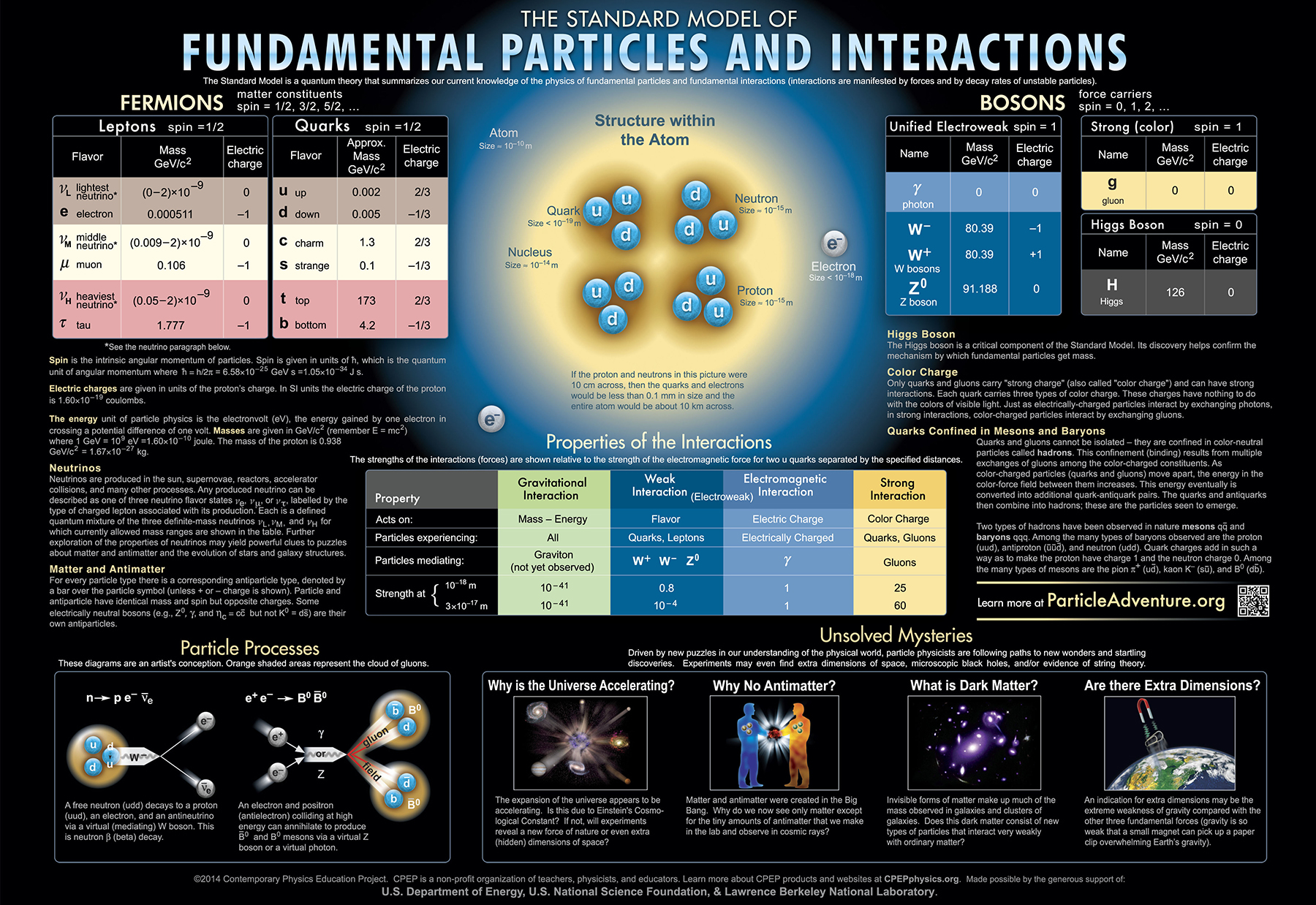

Se vos perguntar qual a coisa mais pequena que conhecem, o que é que vos vem à cabeça? Algumas pessoas dirão uma partícula de poeira, outras uma célula, ou um átomo, ou ainda um micróbio…e poderia continuar a enumerar mais exemplos. Na realidade, a coisa mais pequena que conhecemos, são as partículas elementares, que são o objecto de estudo em física de partículas. Estou certa que a mais conhecida das partículas elementares é o electrão, que muita gente conhece. Mas existem muitas mais, os quarks, os neutrinos, os muões e todas elas ainda têm as suas versões de antimatéria.

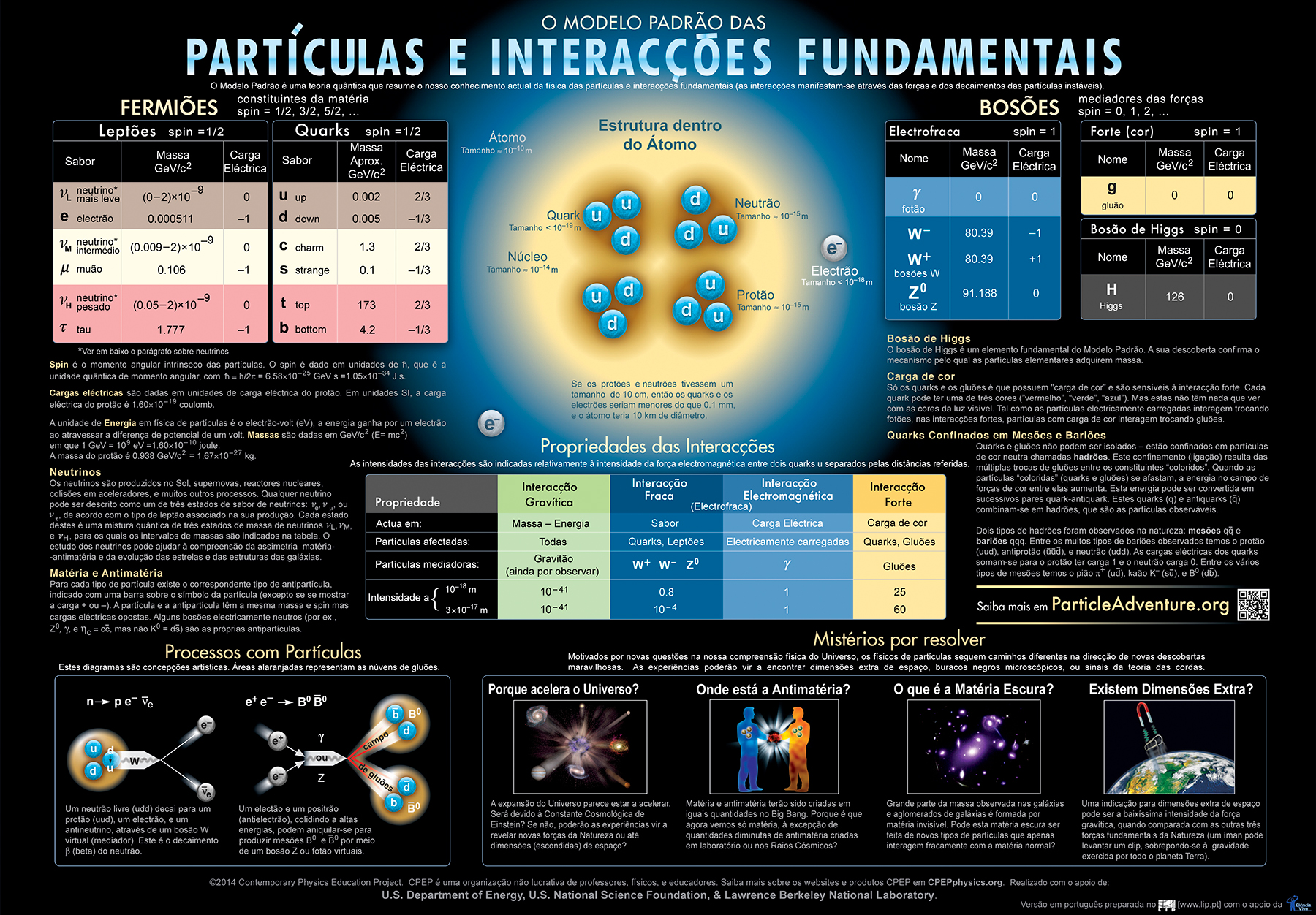

Descrição do modelo padrão, atualmente aceite, para descrever as partículas fundamentais e as suas interações. Versão pdf da imagem

Mas porque é que nós estudamos estas partículas? O nosso objectivo é compreender as suas características e as suas interações e aprender mais sobre de onde viemos, como funcionamos e para onde vamos. Uma forma de estudar isso em laboratório é fazer chocar estas partículas e analisar o que acontece após esse choque. É isso mesmo que fazemos no CERN em diversas experiências. Por exemplo, eu sou membro da colaboração AMBER, uma experiência recente, aprovada em Dezembro de 2020, e que tem, entre outros, o objectivo de estudar os hadrões, partículas mais complexas formadas por partículas elementares, e perceber a origem da sua massa.

Fotografia tirada em 2016, na exposição comemorativa dos 30 anos do LIP, onde sou investigadora.

Na imagem vê-se um modelo da simulação de uma colisão típica tal como acontece no LHC, o maior acelerador de partículas do mundo, localizado no CERN.

E como é que esses estudos são feitos? Em física de partículas os aparatos experimentais são enormes, os detectores de AMBER estendem-se por mais de 50 metros. As partículas de feixe, piões, neste caso, viajam ao longo de um túnel até chegarem à área experimental e chocarem com um alvo de material, também ele formado de partículas, tais como protões. Dessas interações saem novas partículas. Estas partículas vão viajar através dos detectores e, com a sua passagem, deixar sinais elétricos neles. Com base nessa informação é-nos possível identificar quais foram essas partículas e as suas características. Após uma análise estatística em que são contabilizados os diferentes tipos de partículas, com certas características, é possível confrontar o conhecimento atual com os resultados experimentais, e daí confirmar ou refutar a sua validade. E é assim que se vão fazendo os avanços para compreendermos cada vez melhor o mundo que nos rodeia.

Autora:

Márcia Quaresma é mestre no Instituto Superior Técnico (IST), em Engenharia Física Tecnológica. Também no IST e a trabalhar no Laboratório de Instrumentação e Física Experimental de Partículas (LIP) concluiu o seu doutoramento em 2016, dedicando-se ao estudo da estrutura do protão, a partícula que constitui toda a matéria que conhecemos. Mais tarde, mudou-se para Taiwan, do outro lado do mundo, para continuar a sua investigação sobre a estrutura da matéria. Permaneceu lá durante dois anos e no final de 2019 regressou a Portugal. Agora é investigadora no LIP, onde integra o grupo “Partons and QCD”, envolvido em duas experiências do CERN, COMPASS e AMBER. Juntou-se ao primeiro ano da Soapbox Science em Portugal, em 2020, como voluntária e não hesitou em fazer parte da equipa da organização em 2021.

❉ ❉ ❉

Organização:

Email: soapboxscience.lisbon@gmail.com

Em colaboração com:

❉This is the first article in a series of articles prepared by our collaborators from SoapBox Science Lisbon. We will publish them regularly, first from the organization team and followed by the speakers. The articles will cover different topics having in mind the perspective of Women in Science. Stay tuned for new upcoming articles. This year the second edition of the Soapbox Science Lisbon event, to promote women in science will happen on 23rd of October, so save the date!

What does a particle physicist do?

By Márcia Quaresma

Since I was young, in the beginning of middle school, I decided that I wanted to study physics in university. At that time, I was not even aware that particle physics was an area in the field of physics. The closest of it that I was aware of was nuclear physics, which I believe many people have already heard about. But what about particle physics, does the population know what it is?

When I arrived at the university, in 2005, in one of my first classes, the professor talked a lot about CERN, which I had already heard, but at that point I realized its real dimension. At the time, few people were aware of it. I believe that nowadays, after 16 years, and after the well announced Higgs boson discovery in 2012, more and more people know about CERN. This laboratory, on the border between France and Switzerland, is the biggest in Europe, where thousands of scientists join efforts to learn more about the most elementary particles that we know.

If I ask you which is the smallest thing that you know, what would come to your mind? Some people will say a dust particle, others a cell, or an atom or even a microbe…and I could continue to enumerate more examples. In truth, the smallest things we know are the elementary particles, that are the study subjects in particle physics. I am certain that the most known one is the electron, which many people heard about. But there are many more, the quarks, the neutrinos, the muons and all of them also have their antimatter versions.

Description of the standard model, currently accepted, to describe the fundamental particles and their interactions. pdf version of the picture

But why do we study these particles? Our goal is to understand their features and their interactions and learn more about where we came from, how we work and where we go. A way to study it in the laboratory is to do particle collisions and analyse what happens after those shocks. This is what we do at CERN in many different experiments. For example, I am a member of the AMBER collaboration, a recent experiment, approved in December 2020, which has, among others, the goal to study the hadrons, complex particles made by elementary ones, and understand their mass origin.

Picture taken in 2016, in the exhibition to celebrate the 30th anniversary of LIP, where I am a researcher.

In the image we see a simulation model of a typical collision such as it happens at LHC, the largest particle accelerator in the world, located at CERN.

And, how are these studies done? In particle physics, the experimental apparatus are huge, the AMBER detectors extend for more than 50 meters. The beam particles, pions, in this case, travel in a tunnel till they reach the experimental area and shock with a target of material, also made by particles, such as the protons. In these interactions new particles are created that travel through the detectors and leave electrical signals on their passage. Based on this information it is possible to identify which particles were created and their features. After a statistical analysis, where we account for the different types of particles with certain features, it is possible to confront the current knowledge with the experimental results and confirm or disprove their validity. This is how the advances are made to better understand the world around us.

Author:

Márcia Quaresma did her masters at Instituto Superior Técnico (IST), in Technological Physics Engineering. Also at IST and working in Laboratório de Instrumentação e Física Experimental de Partículas (LIP) she completed her PhD in 2016, studying the structure of the proton, the particle that constitutes all the matter we know. Later she moved to Taiwan, on the other side of the world, to continue her research in the structure of the matter. She stayed there for two years and at the end of 2019 moved back to Portugal. Now she is a researcher at LIP, where she integrates the group “Partons and QCD”, involved in two CERN experiments, COMPASS and AMBER. She joined the first year of Soapbox Science in Portugal, in 2020, as a volunteer and could not hesitate to become part of the organisation team in 2021.

❉ ❉ ❉

Organizers:

Email: soapboxscience.lisbon@gmail.com

In collaboration with:

Leave a Reply