Vida em Marte

Vida em Marte

Neste mês em que chegam a Marte três missões espaciais com o propósito de continuar a desvendar os mistérios do planeta vermelho, regressamos à história da investigação humana ao quarto planeta. Vamos debruçar-nos sobre o maior dos enigmas: terá alguma vez havido, ou haverá, vida em Marte?

Autor: José Saraiva

José Saraiva é geólogo de formação. Licenciado pela Univ. Coimbra, fez um Mestrado no IST e por lá ficou muitos anos como bolseiro de investigação. Marte e outros planetas foram alvo de várias investigações sob o prisma da Análise de Imagem ao longo desses anos. Actualmente é Coordenador de Projectos no NUCLIO, de que é colaborador há muitos anos.

Nota: o autor do texto não escreve segundo o novo Acordo Ortográfico.

⬇︎ Clique, abaixo, para ler cada uma das partes deste tema

Vida em Marte – Parte 1

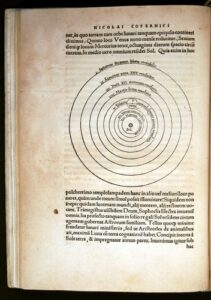

Não vale a pena tentar saber quem primeiro identificou estrelas e planetas, e como os imaginou. A história humana profunda é uma estrada longa e com esparsos marcos. Apesar do papel da Europa na ciência moderna, é notoriamente difícil avaliar as ideias que circulavam noutras civilizações que dominavam outras áreas deste nosso mundo. Que elas existiam, não há dúvida: o cérebro humano não ganhou especiais capacidades na Europa. Mas foi lá que, no começo do século XVII, a Terra se viu transformada em planeta, deixando a sua posição central e fixa no Sistema Solar e assumindo o seu lugar entre os outros astros errantes, graças às observações de Galileo e aos cálculos de Kepler, que permitiram confirmar a anterior proposta heliocêntrica de Copérnico, dada à estampa na forma escrita a meio do século anterior.

Mas ao mesmo tempo, houve outra transformação: os planetas passaram de meras luzes no céu a algo mais; se a Terra era como eles, era lógico que eles fossem também como a Terra: mundos. E nos mundos havia, muito naturalmente, vida, habitantes, civilizações.

Um dos primeiros a abraçar essa ideia foi um padre italiano, Giordano Bruno. Queimado em Fevereiro de 1600 na fogueira pela Inquisição (ou melhor, pelas autoridades civis a quem foi entregue para execução), como herético, ainda hoje se debate o papel que as suas ideias sobre um Universo infinito e cheio de vida tiveram na sua condenação (na realidade, não havia para ela falta de motivos, muitos deles teológicos).

Ao longo do século XVII, as ideias copernicanas foram ganhando aceitação. Em 1686, Fontenelle publicou em França uma das primeiras obras de divulgação da teoria heliocêntrica, onde se incluía uma especulação sobre a vida extraterrestre. Outros, como Huygens – astrónomo neerlandês que fez ele mesmo várias e importantes observações a Marte –, acreditavam piamente que, tal como a Terra fora criada para usufruto da Humanidade, os outros planetas teriam sido criados para usufruto dos seus habitantes. Adiantavam-se mesmo palpites sobre a natureza física e a moral desses extra-terrestres.

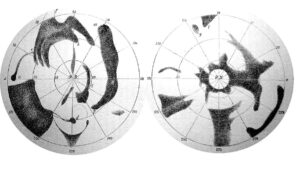

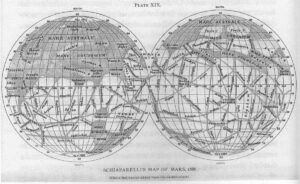

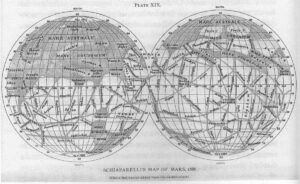

Marte começava a ser objecto de estudo de inúmeros astrónomos, que aproveitavam as melhorias introduzidas no telescópio para aprofundarem o seu conhecimento sobre o planeta vermelho, cuja superfície podia ser vista e analisada a partir da Terra. Identificadas áreas de diversa cor e tonalidade, não tardaram a surgir mapas de Marte desenhados a partir das observações. Dentro do espírito de analogia com a Terra, em Marte existiriam continentes e oceanos, desertos, zonas com vegetação, lagos, ilhas e estreitos. Ao longo do século XVIII, todos eles foram sendo baptizados pelos cartógrafos, ao sabor das suas simpatias pessoais e nacionais – e, naturalmente, ninguém conseguia impor as designações que escolhera ao conjunto da comunidade astronómica.

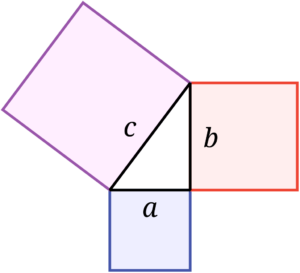

Entretanto, as ideias para contactar os habitantes de Marte também surgiam. Já no século XIX, Gauss propôs que a melhor forma de enviar uma mensagem aos marcianos era através da geometria e da matemática. Sugeriu portanto que se criasse na tundra siberiana um enorme campo triangular semeado com um cereal de tom claro, ladeado por outros três, quadrados, com tons diferentes. A delimitar estas searas geométricas, pinheiros de tom escuro. A ideia não avançou.

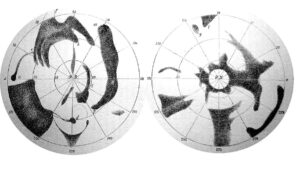

A meio do século, um padre italiano, Angelo Secchi – conhecido por diversas outras contribuições para a Ciência – foi o primeiro a usar o termo “canale” para descrever algumas zonas estreitas e escuras da superfície marciana. O termo foi depois também utilizado por Schiaparelli em 1877; o astrónomo italiano aproveitou a oposição de Marte que ocorreu nesse ano para conduzir um cuidado programa de observação do planeta, e detectou várias linhas finas, escuras e rectilíneas na sua superfície. Designou-as como “canali”… e assim começou um longo debate, que se prolongou para o século XX.

As opiniões dividiam-se: havia quem os visse, e quem não os visse (outros observadores, como Green – que foi à Madeira fazer as suas observações em 1877 – propunham mapas marcianos sem quaisquer linhas do género). Mas, mais importante ainda (e um tema sobre o qual Schiaparelli achou prudente não tomar posição), havia discussão sobre a sua origem: seriam naturais, ou artificiais? Se fossem artificiais, a existência de marcianos inteligentes ficaria comprovada, claro. Era a opinião de Flammarion – o astrónomo francês publicou várias obras sobre a pluralidade dos mundos (habitados) e focou-se especialmente em Marte, debatendo as condições de habitabilidade do planeta (curiosamente, uma palavra que, mais de um século depois, assume de novo o papel principal no estudo de Marte). Um leitor americano foi fortemente influenciado por essa opinião. Chamava-se Percival Lowell.

Lowell não tinha formação em astronomia. Mas tinha vontade, empenho, e dinheiro. Fez construir um observatório perto de Flagstaff, no Arizona, EUA, e dedicou-se ao estudo de Marte e dos seus canais, cuja natureza artificial não lhe levantava qualquer dúvida. Publicou e divulgou largamente as suas ideias e conclusões, e tornou os marcianos uma realidade na opinião popular.

Marte tinha aparecido também na Literatura. A Ficção Científica dava os primeiros passos, e o planeta vermelho e os seus habitantes ocupavam lugar de relevo: em 1880, o inglês Percy Gregg publicou Across the Zodiac, e em 1897 surgiu Auf zwei Planeten, do alemão Kurd Lasswitz (a primeira “invasão” marciana à Terra). Mas um ano depois apareceu uma obra muito mais conhecida: A Guerra dos Mundos, de H. G. Wells. Nesta, os malévolos marcianos lançam-se à conquista da Terra, exibindo uma clara superioridade tecnológica e militar (uma ideia que se fundamentava na suposta maior antiguidade de Marte e da sua civilização relativamente à Terra), antes de serem vergados pelos micróbios terrestres. Marte e os marcianos estavam definitivamente implantados na imaginação popular – e assustavam, como Orson Welles comprovou quarenta anos mais tarde, com a sua dramatização radiofónica da chegada dos marcianos a solo americano, adaptada do romance de Wells.

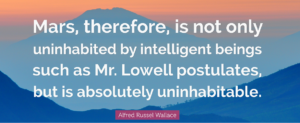

Na frente científica, para lá dos astrónomos de renome que não confirmavam a presença dos canais marcianos, como era o caso do franco-grego Antoniadi, também havia quem demolisse as ideias de Lowell sobre a possibilidade de vida em Marte; Alfred Russell Wallace, cujas ideias sobre evolução natural tinham quase obrigado Charles Darwin a publicar a sua Origem das Espécies, dedicou algum tempo a analisar o que se sabia realmente de Marte (como por exemplo a aparente ausência de vapor de água na sua atmosfera), e publicou em 1907 Is Mars Habitable?, que concluía com um retumbante não.

Contudo, essa conclusão científica não fez mudar a opinião de Lowell, que faleceu em 1916, ainda e sempre convencido da realidade dos canais e dos marcianos. Nem dos muitos que continuaram a aceitá-la, defendê-la e utilizá-la, como Edgar Rice Burroughs na sua popular série sobre as aventuras de John Carter em Barsoom… Por outro lado, Schiaparelli tinha triunfado noutro domínio: os seus mapas de Marte, mesmo com canais, tinham adoptado uma nomenclatura de origem clássica, com nomes gregos e latinos, para a geografia marciana – e foi essa que se impôs e se manteve em utilização até aos nossos dias.

Vida em Marte – Parte 2

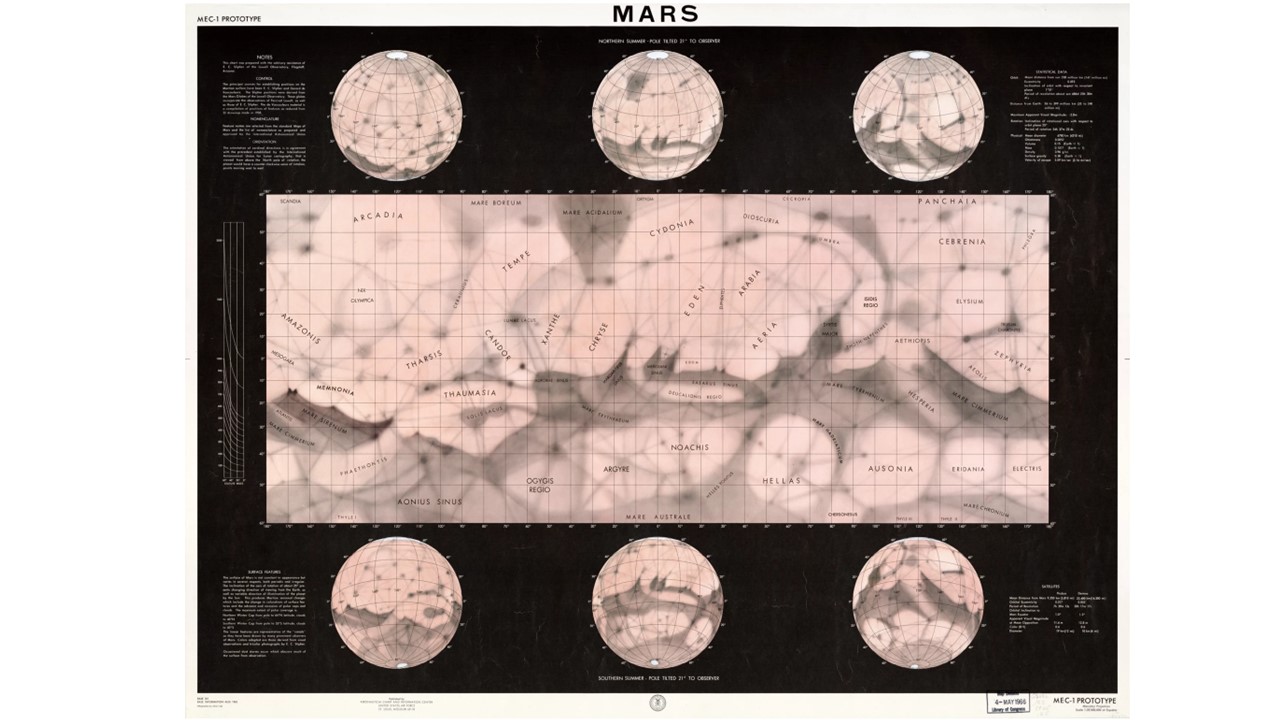

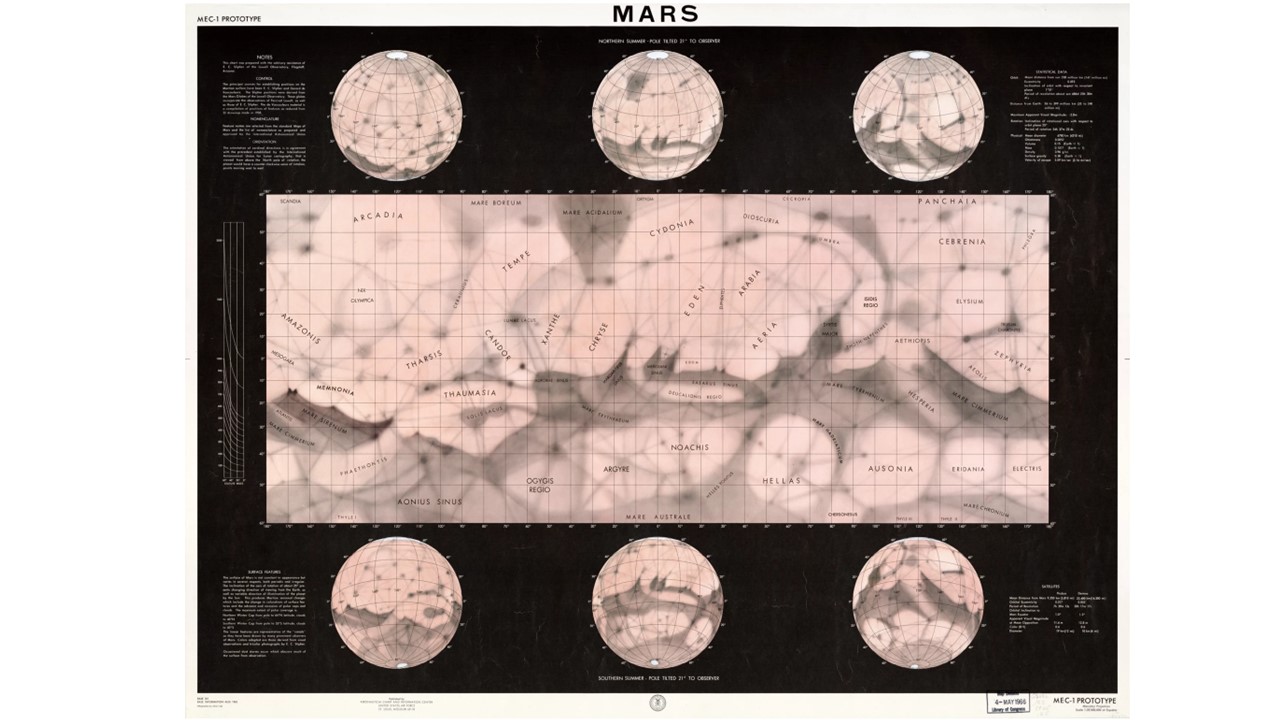

A Era Espacial tinha começado havia pouco tempo, mas Marte era evidentemente um dos principais alvos do interesse dos cientistas. Em 1962, a Força Aérea dos EUA publicou o que era, de acordo com o pensamento dos responsáveis, o mais exacto mapa de Marte que era possível criar com o conhecimento disponível. E nele figuravam ainda algumas estruturas estreitas e escuras que podiam ser interpretadas como canais…

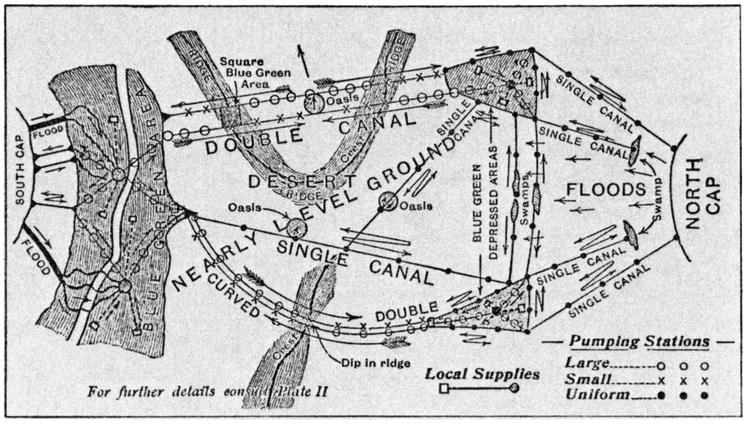

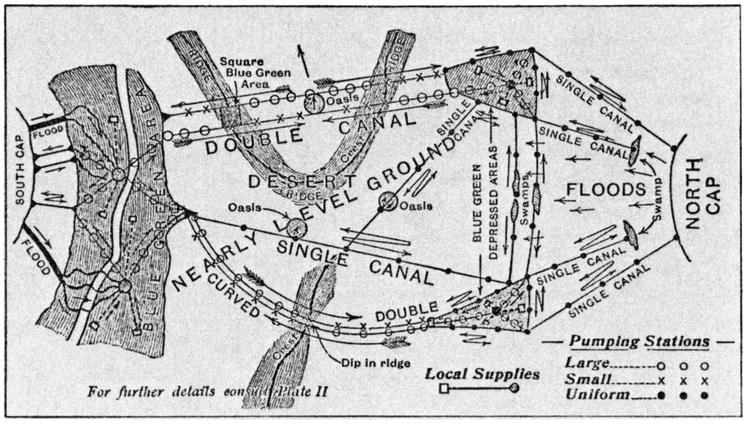

Ao longo dos anos do século XX que tinham decorrido entretanto, a discussão tinha continuado. Mesmo quem não era propriamente um especialista em astronomia usava o seu conhecimento para dar peso à realidade dos canais. O americano Housden mostrou num livro dos anos 20 como os marcianos teriam organizado hidraulicamente o seu sistema de abastecimento de água às cidades das zonas temperadas a partir dos pólos e dos seus gelos…

Há muitos outros exemplos de livros onde se debatia ainda e sempre Marte e as suas condições ambientais. Um estudo bastante exaustivo daquilo que a ciência sabia sobre Marte é, por exemplo, Physics of Planet Mars, de Gerard de Vaucouleurs em 1954, com capítulos sobre a atmosfera, a climatologia, a água, a superfície e a constituição interna de Marte. A possibilidade de vida não era mencionada…

Na realidade, havia ainda, no campo científico, quem defendesse a existência dos canais. E Earl Slipher, que trabalhara no Lowell Observatory, era um deles, e foi ele o principal envolvido na feitura do tal mapa…

A verdade é que, depois de vários falhanços soviéticos, os EUA conseguiram lançar uma de duas sondas a caminho de Marte em 1964. A Mariner 4 (a 3 teve um fim prematuro, poucas horas depois do lançamento) passou (relativamente) perto de Marte em Julho de 1965 e obteve algumas imagens da superfície. Analisadas estas, tornou-se óbvio que nas zonas observadas não havia traços de canais, de civilizações marcianas, nem de qualquer forma de vida. Na realidade, Marte parecia tão árido e craterizado como a Lua. Nos anos seguintes outras duas missões do mesmo género não fizeram mais do que confirmar essa impressão. Mas a verdade é que a área observada continuava a ser uma pequena proporção da superfície do planeta. Era preciso mais. Em 1971, americanos e soviéticos lançaram ambiciosas missões ao planeta vermelho.

A missão soviética não foi propriamente um êxito; apesar de os orbitadores terem funcionado, os módulos de superfície não tiveram sorte. Ambos a alcançaram, mas só um deles enviou dados… durante 20 segundos, e uma imagem em que nada é discernível. Ainda assim, foram os primeiros objectos de fabrico humano a atingirem a superfície de Marte.

A missão americana ficou reduzida a metade logo à partida, já que a Mariner 8 ‘preferiu’ mergulhar no Atlântico. Mas a Mariner 9 entrou em órbita de Marte no fim de 1971 (e por lá continua, desactivada embora). Na altura, Marte estava dominado por uma tempestade de poeira global (o que poderá ter tido alguma coisa a ver com os falhanços soviéticos), e a sonda esperou, e esperou, até começar a vislumbrar a superfície. Obteve depois imagens de toda ela, e fez descobertas surpreendentes: os grandes vulcões, o enorme desfiladeiro, a estrutura das calotes polares… mas nada de vida. Por outro lado, canais… bem, sim: naturais, mas há muito tempo secos. Ainda assim, as evidências do gelo e da antiga presença de água voltaram a dar fôlego à questão da vida em Marte. E assim, confirmou-se que era preciso ir até à superfície do planeta, procurá-la onde ela poderia estar. Mas como? A discussão foi longa; havia muitas ideias; já se sabia que, a existir, a vida seria por certo microscópica. Ainda assim, levar instrumentos que mostrassem a superfície aos olhos humanos era uma opção quase obrigatória; câmaras, portanto. Um microscópio associado poderia mostrar micróbios, mas operá-lo seria quase impossível.

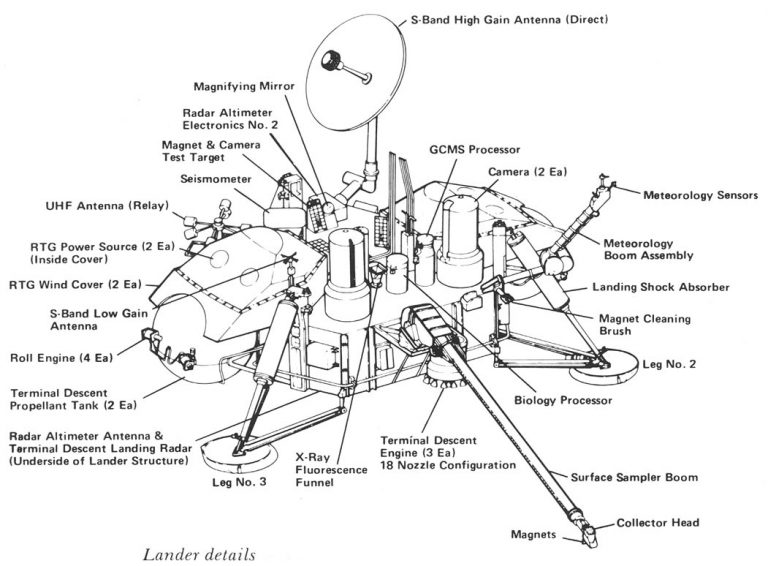

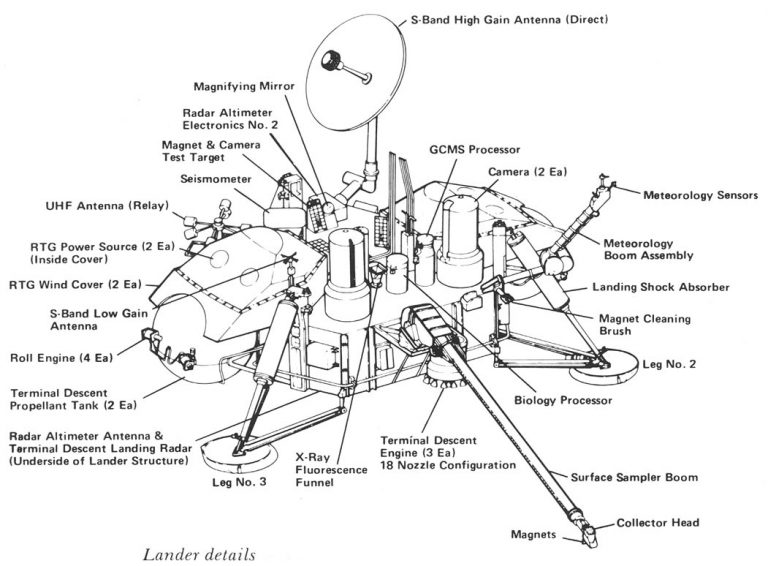

Alguns anos mais tarde, uma nova missão americana seguiu para Marte. A missão Viking era composta por dois orbitadores e dois módulos de superfície. A bordo destes seguiam umas poucas experiências que, ao fim de longa e acirrada discussão, se pensava poderem dar uma resposta cabal à questão da existência (ou não) de vida em Marte.

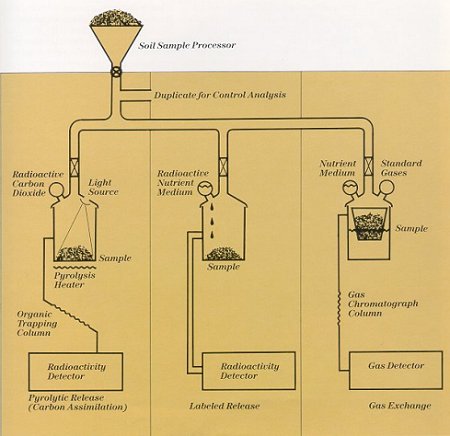

A detecção teria que ser indirecta, já que o microscópio tinha sido riscado. Para isso, três experiências tinham sido seleccionadas; ou melhor, tinham sobrevivido a todas as análises, cabiam num espaço de pouco mais de trinta centímetros de lado, e iam (claramente…) resolver o assunto sem qualquer ambiguidade… Todas elas se baseavam, de alguma forma, na resposta metabólica dos eventuais micro-organismos marcianos.

Havia outros intrumentos a bordo, claro: um sismómetro (infelizmente instalado no corpo da própria sonda, o que impediu a detecção clara de um sinal sísmico, devido às vibrações de outras origens que eram sentidas), as câmaras, antenas, sensores meteorológicos, e um braço articulado com uma pá na ponta, para recolher amostras de solo. E havia um espectrómetro de massa, que teria um papel de relevo na história.

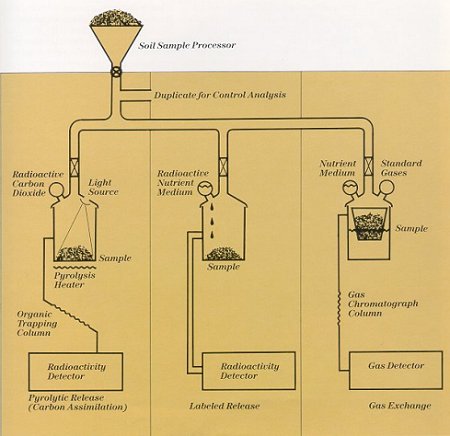

Voltemos às três experiências principais. A primeira, a da troca gasosa, consistia em expor uma amostra de solo marciano a nutrientes (levados da Terra, evidentemente), e esperar para ver se havia alguma reacção, como libertação de gases. Se ela ocorresse, a amostra de solo seria esterilizada por aquecimento, e a experiência repetida (qualquer vida teria sido aniquilada, e nada devia acontecer). A segunda, a libertação por pirólise, expunha a amostra de solo marciano a luz com as mesmas características da luz solar em Marte, enquanto lhe era fornecido CO2 radioactivo, que se esperava que fosse aproveitado pelos eventuais organismos presentes; depois, o gás radioactivo era removido, tudo era vaporizado, e se houvesse ainda radioactividade seria devida a esse uso – portanto, vida! E a terceira, a da libertação marcada, recorria também a um caldo de nutrientes para a amostra de solo marciano, mas desta vez também “marcado” por CO2 radioactivo. Qualquer produto metabólico produzido por seres vivos incluiria esse CO2 e revelaria radioactividade.

Parecia simples, mas era evidente que havia diferenças de opinião entre os responsáveis pelas três experiências.

No oitavo sol depois da descida da Viking 1, a pá recolheu uma amostra de solo que foi levada para bordo, e imediatamente distribuída pelas três experiências… e a confusão começou. Na primeira experiência, em pouco tempo, verificou-se uma tremenda libertação de gases – demasiado rápida, e do tipo errado: oxigénio! Não era uma reacção esperada, e só provocou mais perguntas. Na segunda, houve uma detecção de radioactividade, mas pequena, e a dúvida instalou-se. Na terceira também se detectou radioactividade, e muita. Para o seu autor, Gilbert Levin, não havia dúvidas: a sua experiência detectara vida em Marte! (E, ao fim de todos estes anos, ele mantém a mesma posição.)

Mas essa opinião estava longe de ser unânime. E depois, novas amostras de solo foram analisadas pelo espectrómetro de massa, e praticamente não foram detectados quaisquer compostos orgânicos na terra marciana. Sem eles, como seria possível a vida? As experiências foram repetidas, e analisadas, e discutidas. No primeiro caso, especulou-se que o resultado podia ser devido à presença de peróxidos (que sabemos agora ser realidade). No segundo, foi tentada uma variante, aquecendo (esterilizando) o solo antes de a efectuar. Os resultados continuaram a não ser conclusivos… Na terceira experiência, seguiu-se o mesmo caminho, e aqui os resultados foram exactamente os que se podiam prever: à medida que a temperatura subia, a resposta diminuía. Portanto, deviam ser micróbios os responsáveis! Mais tarde, Levin fez experiências com solo antárctico e obteve exactamente os mesmos resultados: nada de compostos orgânicos (aparentemente), mas vida evidente. E depois, houve quem detectasse mudanças de cor nalgumas das rochas vistas pelas câmaras… e assim, a presença de líquenes em Marte (ou organismos similares) foi mesmo aventada.

Contudo, a verdade é que, com a excepção de Levin e seus seguidores, o consenso na comunidade científica foi que não havia provavelmente vida em Marte. Passaram já muitos anos, e na realidade a resposta mais comum hoje em dia é: não sabemos. As experiências que as Viking levaram até Marte não eram conclusivas. Talvez se pudesse ter enviado outras, mas na altura não havia forma de fazer uma opção em bases mais sólidas… E Levin continua a dizer que a vida já foi detectada em Marte.

As Viking – neste caso os módulos orbitais – ficaram também famosas por outra razão. Enquanto se tentava localizar um ponto ideal para proceder à descida da Viking 2, uma imagem levantou grande celeuma. Na região que Schiaparelli baptizara como Cydonia, uma região de planícies e mesas isoladas, o jogo de luz e sombras deu origem a algo que fazia lembrar uma face humanóide. Ao longo dos anos, vários iluminados tomaram essa imagem como prova da existência de uma civilização marciana desaparecida, ou de uma mensagem deixada por ETs à Humanidade. Estudaram ângulos, orientações, dimensões, relações com outras estruturas próximas (entre as quais avultavam as pirâmides, sinal ‘certo’ da presença de extra-terrestres). Acusaram a NASA de querer esconder o facto, de se recusar a ir verificar a suposta realidade artificial dessas estruturas. E por fim, quando imagens mais detalhadas de sondas mais avançadas demonstraram que se tratava apenas de um caso de pareidolia, houve quem levantasse a absurda hipótese de que a ‘face’ tinha sido deliberadamente destruída à bomba por uma das sondas entretanto desaparecidas na chegada a Marte.

Depois desses anos de intensa discussão, Marte pareceu ter caído um pouco no esquecimento. Os anos 80 foram os das passagens das sondas Pioneer e Voyager pelos gigantes gasosos e seus séquitos de satélites, cada um mais assombroso do que os outros. E do Space Shuttle, que se sonhava poder abrir um mais célere acesso ao espaço.

Todavia, o planeta vermelho ainda tinha muito que revelar.

Vida em Marte – Parte 3

Por motivos de força maior, a publicação deste tema do mês teve de ser interrompida. Será retomada logo que possível.

Agradecemos a vossa compreensão.

Vida em Marte – Parte 4

Por motivos de força maior, a publicação deste tema do mês teve de ser interrompida. Será retomada logo que possível.

Agradecemos a vossa compreensão.

Life on Mars

This month, three space missions arrive at Mars, with the goal of continuing to probe the mysteries of the red planet. We take the opportunity to go back to the history of the human understanding of the fourth planet. We will look into the biggest issue: was there ever, or is there life on Mars?

Author: José Saraiva

José Saraiva trained as a geologist. He got a degree from the Univ. of Coimbra, and then an M. Sc. from IST (Technical University of Lisbon), where he spent long years as a project researcher. Mars and other planets, through the lens of Image Analysis, were the target of several researches during those years. Currently, he is a Project Coordinator at NUCLIO, after many years of collaboration.

⬇︎ Click below to read each part of this theme

Life on Mars – Part 1

It’s no use trying to find out who was the first to identify stars and planets, and what did she think of them. The deep history of Humankind is a long road with few signposts. Though Europe assumed a key role in the development of modern science, it’s rather difficult to evaluate the concepts that dominated thought in other civilizations in other parts of this world of ours. They were there, of course: the human brain did not gain special powers in Europe. Anyway, it was there that, at the beginning of the 17th century, Earth was suddenly transformed into a planet, leaving behind its central and motionless position in the Solar System and taking its place among the other wandering celestial bodies – thanks to the observations of Galileo and the mathematical musings of Kepler, that served to confirm the heliocentric proposal of Copernicus, put forward in written form in the middle of the previous century.

At the same time, another transformation came into effect: the planets were no longer just tiny lights in the sky; if Earth was like them, a planet, it was only logical that they too were like the Earth: worlds. Places where there was, naturally, life, inhabitants, civilizations.

One of the first to embrace that idea was an Italian priest, Giordano Bruno. Burned at the stake by the Inquisition (or by the civil authorities, at their bequest) in February 1600, as an heretic, there is still a debate about the role his ideas about an infinite Universe where life thrived had on his sentence (there was no lack of theological arguments for the condemnation).

Copernican ideas gained acceptance through the 17th century. In 1686, Fontenelle published in France one of the first books to publicize the heliocentric theory, and in there he included some speculation on extraterrestrial life. Other, like Huygens – a dutch astronomer that conducted many and important observations on Mars – firmly believed that, since Earth had been created for the benefit of its inhabitants, the other planets had to have been created for the benefit of their inhabitants. There were even guesses on the physical nature and morals of those beings.

Mars was an object of study by countless astronomers, that took advantage of the improvements made to the telescope to improve their knowledge of the red planet, since its surface could be viewed and analysed from Earth. Areas of diverse colour and tone were identified, and maps were prepared from the observations. In the spirit of analogy with Earth, it was clear that Mars had its continents and oceans, deserts, vegetated areas, lakes, islands and straits. The 18th century saw many maps of Mars, in which the cartographers baptized the features according to their personal and national choices – and, of course, that meant that no one was able to impose the names he had picked to the whole of the astronomical community.

In the meantime, ideas to communicate with the inhabitants of Mars were proposed. Gauss, at the beginning of the 19th century, suggested that the best way to make contact was through mathematics and geometry. Thus, he advised the creation of a huge triangular field in the Siberian tundra, where a light-coloured cereal would grow; on its faces, there would be different coloured squares. The borders would be highlighted by dark pinewoods. The idea was never followed.

In the middle years of the century, an Italian priest, Angelo Secchi – known from contributions to other fields of Science – became the first to employ the word ‘canale’ to describe some narrow and dark areas of the martian surface. The same word was then used by Schiaparelli in 1877; the Italian astronomer used the opposition of Mars that occurred in that year to conduct an extensive program of observation, during which he detected several dark, thin and straight lines on the surface. He called them ‘canali’… and so a long debate started, that continued well into the 20th century.

Opinions were divided: some saw them, some did not (other observers such as Green – that went to Madeira island to realise his observations in 1877 – proposed martian maps with no trace of that type of lines). More important still was the question, on which Schiaparelli prudently remained silent: were they natural, or artificial? If the latter was true, the existence of intelligent martians would be undeniable. That was the opinion of Flammarion – the French astronomer published several books about the plurality of (inhabited) worlds, and focused on Mars, debating the conditions of habitability of the planet (a word that, more than a century later, has again taken centre stage in martian research). An American reader was strongly influenced by that view. His name was Percival Lowell.

Lowell had no formal training in Astronomy. But he had the will, the commitment and the money. He built an observatory on the outskirts of Flagstaff, in Arizona, USA, and dedicated his life to the study of Mars and its canals, whose artificial nature was not, for him, in any doubt. He published and spread wide and far his ideas and conclusions, and made martians real in public opinion.

Mars had suddenly emerged into Literature. Science Fiction was taking its first steps, and the red planet and its inhabitants took pride of place: in 1880, an Englishman, Percy Gregg, published Across the Zodiac, and in 1897 the German Kurd Lasswitz authored Auf zwei Planeten (featuring the first martian invasion to Earth). One year later a much more well-known book saw the light of day: War of the Worlds, by H. G. Wells. In it, the evil martians launch the conquest of Earth, showcasing a clear technological and military superiority (an idea based on the supposed older age of Mars and its civilization when compared to Earth), before facing defeat at the hands (so to speak) of terrestrial microbes. Mars and the martians were forever etched into popular imagination – and scary they were, as Orson Welles confirmed forty years later, with his radio re-enactment of the arrival on American soil of the martians, adapted from the novel.

On the science front, other than the famous astronomers that would not confirm the presence of the canals on Mars, such as the French (of Greek descent) Antoniadi, there were others busy demolishing Lowell’s ideas about the possibility of life on Mars; Alfred Russell Wallace, whose ideas on evolution had practically forced Charles Darwin to publish his On the Origin of Species, dedicated some time to the analysis of concrete data on Mars (such as the fact that there was apparently no water vapour in its atmosphere), and published in 1907 Is Mars Habitable?, a book that gave a very resounding answer: no.

However, that scientific conclusion did nothing to change Lowell’s opinion; he died in 1916, forever convinced of the reality of canals and martians. Nor did it alter the views of the many that continued to accept and defend the idea, and use it, such as Edgar Rice Burroughs in his popular series about the adventures of John Carter in Barsoom… On the other hand, Schiaparelli too had triumphed in another field: in his maps of Mars, even with canals, he had adopted a nomenclature for the martian features based on the classics, with Greek and Latin references – and that became widely accepted, and is still used in our time.

Life on Mars – Part 2

The Space Age had begun recently, but Mars was clearly one of the prime targets for scientific exploration. In 1962, the US Air Force published a map of Mars that was, according to its authors, the most accurate possible, with all the information available. In it, some thin dark features were visible – maybe canals…

The years of the 20th century that had passed had seen the discussion going on. There were those that, not really being an expert in astronomy, still felt they had to add their two cents to the canal controversy. Housden, an American, published a book in the 20s, showing how the martians could have organized their system of canals to provide water to the cities in the temperate areas of the planet, using the ice in the poles…

There are many other examples of books debating Mars and its environment. A rather exhaustive study about Mars came out in 1954; authored by Gerard de Vaucouleurs, Physics of Planet Mars contained chapters about the atmosphere, climatology, water, surface and internal structure of the planet. The possibility of life was not contemplated…

However, the truth was that there were still in the field of science many that defended the reality of the canals. Earl Slipher, who had worked in the Lowell Observatory, was one of them, and he was the main responsible for the creation of that map…

In any case, and after several soviet failures, in late 1964 the USA succeeded in launching a probe towards Mars. Mariner 4 (there had been a Mariner 3 with the same target, but it didn’t go far) flew by Mars in July of 1965, and acquired some pictures of its surface. When these were analysed, it became obvious that the targeted areas did not show any sign of canals, martian civilizations, or indeed any lifeforms. In fact, Mars looked as barren and cratered as the Moon. In the following years, two other missions of the same kind did nothing more than confirm the impression. Still, the area caught in the images was but a small proportion of the whole surface of the planet. More was needed.

In 1971, both Americans and Soviets sent ambitious missions to the red planet. The Soviets did not meet with full success; the orbiters worked, but the descent modules fared much worse. Though both reached the surface, only one of them sent data… for about 20 seconds; this included an image in which nothing can be seen. Still, they were the first man-made objects to reach the surface of Mars.

The American mission was cut in half right at the beginning, since Mariner 8 ‘chose’ do go for a dip in the Atlantic Ocean. Mariner 9, however, entered the martian orbit in late 1971 (and is still there, though inactive). At the time, Mars was dominated by a global dust storm (that had probably something to do with the Soviet mishaps), and so the probe waited, and waited, until it could view the surface of the planet. Then it acquired images of the whole surface, and made many astounding discoveries: large volcanic mountains, a huge canyon that dwarfed the Grand Canyon, the structure of the polar caps… but no life. On the other hand, canals… close: there were channels there, but long dried. Still, the presence of ice and the evidence of surface water in the past breathed new, well, life into the big question of life on Mars. It was then clear that it would be necessary to go to the surface of the planet, and search for it I the place where it could be. But how to do it? The discussion was long; there were many ideas; it was already clear that, if it was there, life would be microscopic. Still, it was obvious that some instrument that could show the surface to human eyes was almost mandatory; so, there would be cameras. A microscope associated with them could perhaps show microbes, but its operation would be almost impossible.

A few years later, a new American mission was launched towards Mars. The Viking mission comprised two orbiters and two descent modules. Onboard there would be a few experiences that, after all the fierce and bitter discussion, were thought to be able to provide a definite answer to the question: was there life on Mars (or not)?

The detection would have to be made indirectly, since the microscope had been scratched. So, three experiences had been selected; or rather, had survived all the analyses, could fit in a space of about thirty centimetres, and would (clearly…) provide an unambiguous answer… All of them were somehow based on the detection of the metabolic response of the would-be martian microbes.

There were other instruments on the modules, of course: a seismometer (unfortunately located in the body of the probe, a fact that precluded the detection of a true seismic signal, due to the vibrations of other origins), cameras, antennas, meteorology sensors, and an articulated robotic arm with a small shovel to collect soil samples. And there was a mass spectrometer, that would assume a pivotal role in the story.

Let’s go back to the three main experiments. The first, the gas exchange, would expose a sample of martian soil to nutrients (taken from Earth, of course) and wait for any reaction, such as the release of gases. If that happened, the sample would be sterilized through heating, and the experience repeated (any lifeforms would have been killed, so nothing should happen). The second, the pyrolytic release, would expose the martian sample to light with the same characteristics of sunlight at Mars, while providing radioactive CO2; it was expected that this would be taken up by the microbes; then, the remaining radioactive gas would be removed, everything was vaporised, and if there was any radioactivity, it would be due to the microbial activity – thus, life! And the third, the labelled release, also made use of a nutrient broth provided to the martian soil, but this one had also been marked with radioactive CO2. Any metabolic product with CO2 would be radioactive.

It all looked simple, but it was already obvious that the authors of the three experiments did not see eye to eye.

In the eighth sol after Viking 1 reached the surface of Mars, the robotic arm collected a soil sample, took it to the probe, and it was distributed among the three compartments, one for each experiment… and things started to get messy. The first experiment saw a vast release of gases – however, too quick and of the wrong kind: oxygen! This was not expected, and it led only to new questions. The second saw some radioactivity, but not much, and so the doubt remained. But the third also detected radioactivity – a lot. For its responsible, Gilbert Levin, there was no doubt: his experience had just detected life on Mars! (And after all these years, he still maintains that opinion.)

However, that idea was far from being unanimous. And then, new soil samples were analysed by the mass spectrometer, and no organic compounds were found on the martian dirt. If they were absent, how could there be life on Mars? The experiments were redone, and analysed, and discussed. In the first case, there was speculation that the result could be due to the presence of peroxides (something we now know to be true). In the second, a new run saw the soil being warmed (sterilized) before exposure to the light and radioactive gas. The results were again inconclusive… The third uses the same approach of warming the sample before doing it, and in this case the results were exactly what could be expected: as the temperature rose, the response diminished. Thus, microbes should be the real reason behind it! Later, Levin conducted similar experiments with Antarctic soil and obtained precisely the same results: no organic compounds (apparently), but obvious life. And then, some people looked at the pictures from the surface of Mars and detected some subtle colour changes in rocks seen by the Viking cameras… and soon there was talk of lichens (or similar organisms) on Mars.

The reality, still, is that – with the exception of Levin and his followers – the scientific community settled into a consensual view, that there probably was no life on Mars. Many years later, the common answer today is: we do not know. The experiments that the Vikings carried to the surface of Mars were not conclusive. Maybe others could have been chosen instead, but at the time there were no foundations to make a more informed choice… And Levin insists that life has already been detected on Mars.

But the Vikings – in this case the orbital modules – also became famous for another reason. While trying to locate an ideal spot to take Viking 2 to the surface, an image they acquired raised a huge controversy. In the region that Schiaparelli had called Cydonia, an area of vast plains and isolated mesas, the play of light and shadow produced something that resembled a humanoid face. Through the years, several would-be experts took that image as proof of the existence of a vanished martian civilization, or of a message to Humanity left by aliens. They studied angles, directions, dimensions, relations with other structures nearby (among these ‘pyramids’, a sur sign that aliens were involved). They accused NASA of trying to hide the fact, of refusing to go and check the reality of the artificial structures. Finally, when new images from more advanced probes revealed that they were just the product of the human pareidolia, some went to the extreme of suggesting that the ‘face’ had been deliberately destroyed by bombs carried by one of the probes that, in the meantime, had been lost when reaching Mars.

After those years of lively discussion, Mars seemed to somewhat fall into oblivion. The 80s saw the visits of the Pioneers and Voyagers to the gaseous giants and their satellites, each one more amazing than the others. And they also gave us the space shuttle, a machine that was supposed to open a quicker access to space.

And yet, the red planet still had much to show us.

Life on Mars – Part 3

Due to reasons of force majeure, the publication of this theme of the month had to be interrupted. It will be resumed as soon as possible.

Thank you for your understanding.

Life on Mars – Part 4

Due to reasons of force majeure, the publication of this theme of the month had to be interrupted. It will be resumed as soon as possible.

Thank you for your understanding.

Leave a Reply