O Céu de Verão

O Céu de Verão

O verão pode ser a estação do Sol, mas quando a noite cai, as atrações são muitas. As temperaturas noturnas amenas são um convite irrecusável para passar as noites olhando as estrelas.

Este ano, a estação oferece duas boas chuvas de meteoros, planetas em posições favoráveis para observação, e um sutil eclipse lunar. É uma excelente época para apreciar a zona ao redor do centro galáctico, ricamente povoada de enxames estelares e nebulosas.

Neste tema do mês, veremos os principais fenômenos astronômicos dos próximos meses, suas constelações características, e objetos celestes de interesse. Prepara-te para férias na companhia dos astros!

Autor: Gustavo Rojas

Doutor em Astronomia pela Universidade de São Paulo (2008), Gustavo Rojas iniciou sua carreira profissional na Universidade Federal de São Carlos, Brasil. Atua há mais de 10 anos nas áreas de divulgação científica e ensino de ciências. É membro da União Astronômica Internacional, Sociedade Astronômica Brasileira, e Sociedade Portuguesa de Astronomia. Faz parte da comissão organizadora da Olimpíada Brasileira de Astronomia e Astronáutica, e foi líder das delegações brasileira (2012-2018) e portuguesa (2019) na Olimpíada Internacional de Astronomia e Astrofísica (IOAA). Foi representante brasileiro do ESO Outreach and Science Network de 2011 a 2018. Atualmente é coordenador de projetos no NUCLIO – Núcleo Interactivo de Astronomia.

Nota: o autor do texto escreve em português do Brasil.

⬇︎ Clique, abaixo, para ler cada uma das partes deste tema

O Céu de Verão – Parte 1

Nesta série de quatro artigos, começaremos com uma visão geral dos principais fenômenos celestes do mês de julho para marcar em vosso calendário. Nas semanas seguintes, abordaremos os meses de agosto e setembro, constelações características, e os objetos de interesse nelas situados.

Afinal, quando é o verão?

Na astronomia, o início do verão setentrional é marcado pelo solstício de junho, quando o Sol atinge a posição mais ao norte na esfera celeste. Nessa data, temos o dia mais longo do ano no hemisfério norte. No entanto, as maiores temperaturas geralmente são registradas um ou dois meses mais tarde. Em 2020, o solstício acontece em 20 de junho às 22:43 (hora de Portugal).

Constelações típicas

No hemisfério norte, o céu do verão é marcado pelo chamado Triângulo de Verão, formado pelas estrelas brilhantes Altair, Deneb e Vega.

Durante todo o mês de julho, podemos ver estas três estrelas bem altas no céu. Ao olhar para o céu por volta das 23h, a mais brilhante delas, Vega, estará praticamente no zênite, o ponto mais alto do céu. Formando a base do triângulo temos Altair (a segunda em brilho e a mais baixa do trio) e Deneb (a mais fraca das três e um pouco acima de Altair).

Vega é a principal estrela da pequena constelação da Lira. Altair é a estrela mais brilhante da constelação da Águia. Da mesma forma, Deneb está associada a uma constelação que representa uma ave, o Cisne. Vamos agora conhecer um pouco mais sobre essas constelações.

Lira, a pequena notável

Existe um ditado que afirma que os menores frascos guardam os melhores perfumes. Podemos dizer que na Astronomia isso às vezes é verdade. Algumas constelações de tamanho reduzido podem guardar tesouros notáveis.

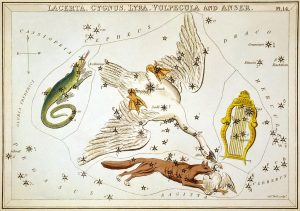

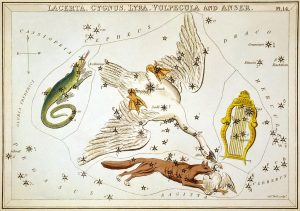

Lira é uma das menores constelações do céu, e simboliza a pequena harpa de Orfeu, o lendário artista da Grécia antiga capaz de encantar a todos com suas harmonias. É uma das constelações presentes no Almagesto, o mais famoso catálogo astronômico antigo, compilado por Claudio Ptolomeu e publicado no século II da nossa era.

O Almagesto contém o brilho e posição de 1022 estrelas, posicionadas em 48 constelações. Este conjunto de constelações sobreviveu ao tempo, e a maioria delas pode ser encontrada na lista das 88 constelações reconhecidas pela União Astronômica Internacional.

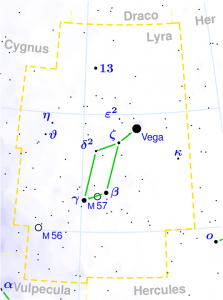

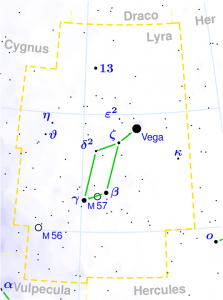

A estrela mais brilhante da Lira, Vega, é uma das mais próximas de nós. Dista apenas 25 anos luz da Terra. Por seu brilho e proximidade, é também uma das estrelas mais bem estudadas do Universo. Vega foi a primeira estrela a ser fotografada e a ter seu espectro registrado. Durante muito tempo, foi a estrela de referência nas escalas de brilho e cor.

Vega não é a única estrela de interesse astronômico na constelação. A vice-campeã em brilho, Beta Lyrae, é um sistema notável. A olho nu, parece ser uma estrela como outra qualquer. Em 1784, o astrônomo John Goodricke descobriu que o brilho dessa estrela variava de maneira regular, semelhante à estrela Algol, na constelação de Perseu.

Goodricke concluiu que, assim como Algol, Beta Lyrae é na verdade um sistema duplo, que sofre um “apagão” a cada 13 dias quando uma das estrelas passa exatamente na frente da outra, provocando um eclipse.

O que Goodricke não sabia é que as estrelas desse sistema estão tão próximas uma da outra que suas formas são distorcidas pela gravidade. A proximidade entre os componentes provoca transferência de matéria de uma estrela para a outra, formando um disco de acreção ao redor do par.

Epsilon Lira é outro sistema múltiplo muito conhecido, composto de pelo menos cinco componentes. Um telescópio amador mostra os quatro mais brilhantes, o que lhe rendeu o apelido de Dupla Dupla.

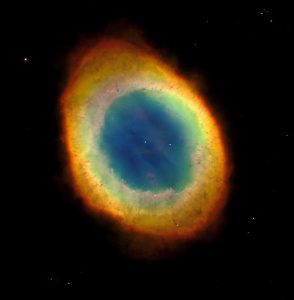

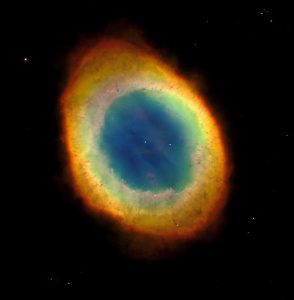

Na Lira também encontramos uma das nebulosas planetárias mais bonitas do céu. Messier 57, mais conhecida como a Nebulosa do Anel, é um alvo favorito dos astrônomos. Resultado da evolução de uma estrela parecida com o Sol, é o retrato de como será nosso futuro distante, daqui a milhares de milhões de anos.

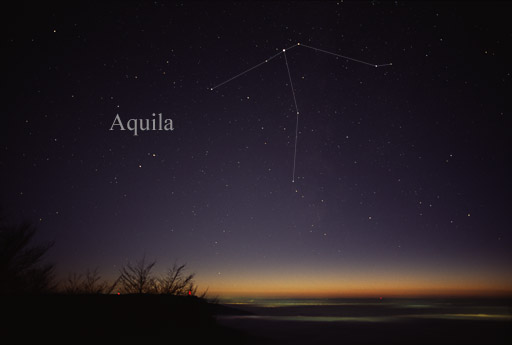

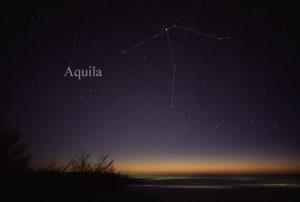

A surpreendente Águia

A Águia também faz parte das 48 constelações do Almagesto. Sua cabeça é marcada por sua estrela mais brilhante, Altair, igualmente uma das estrelas mais próximas da Terra, distante apenas 17 anos luz de nós. Na constelação, Altair está flanqueada por outras duas estrelas que podem ser facilmente visualizadas: Alshain e Tarazed, que formam o pescoço e o corpo da Águia.

No século passado, este trio teve seu brilho desafiado, embora por pouco tempo. Em junho de 1918, uma estrela até então invisível da constelação aumentou subitamente de brilho, superando Altair e chegando a ser a segunda estrela mais brilhante de todo o céu.

Os astrônomos antigos chamavam este fenômeno de Nova, pois imaginavam que eram estrelas novas a surgir no céu. Hoje, sabemos que as Novas são estrelas já bastante evoluídas, assim como suas parentes mais brilhantes, as Supernovas.

As Novas acontecem em sistemas binários, onde uma das componentes é uma anã branca que captura hidrogênio de sua companheira, até que ocorra uma reação nuclear. O brilho da anã branca aumenta muito e volta ao normal após algumas semanas, um processo que em alguns casos pode se repetir diversas vezes.

Novas são fenômenos imprevisíveis, e muitas foram descobertas por astrônomos amadores. Quem descobriu a Nova da Águia em 1918 foi um garoto de 17 anos, Leslie Peltier, que mais tarde viria a se tornar um importante pesquisador de estrelas variáveis.

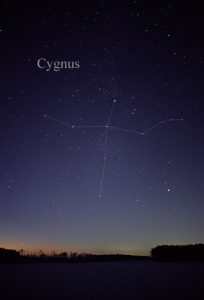

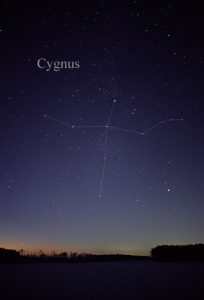

Cisne e suas Joias

A constelação do Cisne é uma das mais conhecidas do céu do hemisfério norte. Suas seis estrelas mais brilhantes formam o asterismo chamado de Cruz do Norte. Os antigos gregos imaginavam que esta cruz representava um Cisne de asas abertas na Via Láctea, que na realidade seria Zeus disfarçado, voando rumo a um encontro amoroso com a ninfa Nemesis. Ptolomeu também incluiu o Cisne em seu Almagesto.

Sua estrela mais brilhante, que marca a cauda do Cisne, é a gigante Deneb, e em seu bico encontramos uma das estrelas mais interessantes do céu: Albireo, que na verdade é um sistema duplo. Quando observada através de um pequeno telescópio, Albireo revela-se um delicado par formado por uma estrela avermelhada e outra azulada, como uma joia celeste de rubi e safira.

Essa coloração é consequência das diferentes temperaturas das estrelas. A temperatura da estrela avermelhada de Albireo é próxima de 4200 graus. Embora isso seja quente o suficiente para derreter um diamante, os astrônomos chamam essas estrelas avermelhadas de estrelas frias. É tudo uma questão de comparação, pois as estrelas azuis como a de Albireo podem ter mais de 12 mil graus de temperatura. Isso é mais que o dobro da temperatura do nosso Sol.

Apesar de parecerem muito próximas uma da outra, as componentes de Albireo estão muito distantes entre si. Acredita-se que levem 100 mil anos para completar uma volta em torno da outra.

No pescoço do Cisne encontramos um objeto enigmático e invisível aos telescópios convencionais. Cygnus X-1 só foi descoberto em 1964 por um experimento pioneiro de astrofísica de raios-X carregado a bordo de um foguete. Cygnus X-1 é um sistema duplo, composto por uma estrela azul supergigante e um objeto compacto invisível, com cerca de 15 massas solares. Parte do gás da

estrela azul é sugada por este objeto, acumulando-se num disco em torno dele. O gás do disco é aquecido a milhões de graus emitindo assim, uma grande quantidade de raios-X.

Embora não seja possível observar diretamente este misterioso objeto, os cálculos não deixam dúvidas. Tamanha quantidade de matéria em um espaço tão confinado só pode ser encontrada no objeto mais extremo do Universo: um buraco negro, onde o campo gravitacional é tão intenso que nem a luz consegue escapar.

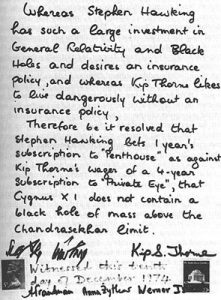

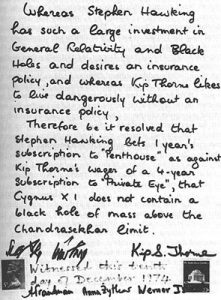

A existência dos buracos negros sempre foi um tópico polêmico na Astrofísica. O buraco negro de Cygnus X-1 foi motivo até de uma famosa aposta envolvendo os renomados cientistas Stephen Hawking e Kip Thorne.

Em 1975, Hawking apostou com Thorne que Cygnus X-1 não abrigaria um buraco negro. Caso vencesse a aposta, ganharia uma assinatura de uma revista de humor, mas se perdesse, pagaria a Thorne a assinatura de uma revista erótica.

Com o avanço das pesquisas sobre Cygnus X1, Hawking finalmente reconheceu, em 1998, que havia perdido a aposta, o que na verdade não o desapontou, já que a maior parte de seu trabalho fala justamente sobre buracos negros.

Na direção do Cisne, também encontramos alguns enxames estelares notáveis. O mais conhecido é M29, que está bastante próximo da estrela Gamma Cygni, situada bem no centro da Cruz do Norte.

Distante 6 mil anos luz da Terra, M29 contém pelo menos 50 membros. Os mais brilhantes são estrelas jovens e azuladas da classe espectral B0. Estima-se que o conjunto foi formado há cerca de 10 milhões de anos, o que o torna um dos enxames estelares mais jovens conhecidos.

Quando observado ao telescópio, as estrelas mais brilhantes de M29 formam uma curiosa figura com um quadrilátero na base, o que deu ao enxame o curioso apelido de Torre de Resfriamento, uma referência à estrutura encontrada em algumas indústrias e usinas nucleares.

O que ver no céu em julho

4/7: A Terra mais longe

Nosso percurso anual ao redor do Sol não se faz em uma trajetória circular. A órbita terrestre é ligeiramente ovalada, e como resultado, a distância Terra-Sol varia ligeiramente ao longo do ano. A aproximação máxima, chamada periélio, acontece em janeiro e mede aproximadamente 147,1. milhões de km. Em julho, é a vez de ficarmos alguns milhões de quilômetros mais longe da nossa estrela. Este ponto na órbita é conhecido como afélio, e nele a distância até o Sol atinge 152,1 milhões de quilômetros

Embora 4 milhões de quilômetros seja um número extremamente grande (mais de 10 vezes a distância até a Lua), não podemos perceber qualquer variação do tamanho aparente do Sol. Apenas em registros fotográficos é que essa diferença de cerca de 3,5% pode ser notada.

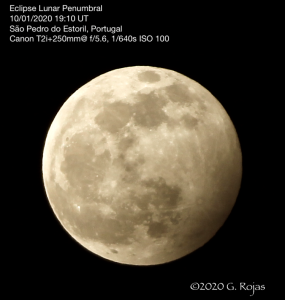

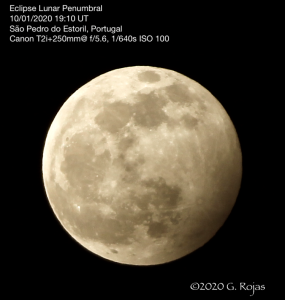

5/7: Lua na sombra

Na noite de sábado para domingo acontece um eclipse lunar penumbral. Neste tipo de eclipse, a Lua atravessa a penumbra, região menos escura da sombra que a Terra projeta no espaço. Eclipses penumbrais são sempre sutis, e dificilmente perceptíveis a olho nu. O fenômeno se torna mais evidente em fotografias ou através de instrumentos ópticos.

De Portugal, será possível acompanhar boa parte do eclipse, que se inicia às 04:07 e atinge o ápice às 5:29.

8/7: A Estrela D’Alva

Para os apreciadores das observações planetárias, julho será um prato cheio. Logo no começo do mês teremos uma boa oportunidade para apreciarmos o planeta mais próximo de nós. Vênus, que aparece como estrela matutina, atinge seu brilho máximo na manhã de 8 de julho. Está logo acima da avermelhada Aldebaran, a estrela mais brilhante da constelação de Touro.

14/7: A noite de Júpiter

Os destaques do mês são as oposições dos dois maiores planetas do Sistema Solar, Júpiter e Saturno. Na astronomia, denominamos como oposição a configuração na qual a Terra se situa exatamente entre o Sol e um planeta superior (órbita externa à da Terra). Nesta ocasião, o planeta apresenta-se mais alto no céu, e também visível durante mais tempo. As noites ao redor da oposição constituem, portanto, a melhor época para observação.

Este ano, Júpiter pode ser visto na direção da constelação de Sagitário, brilhando mais que qualquer estrela da região. Quem tem um telescópio em casa pode aproveitar a oportunidade para se maravilhar com a intrincada estrutura de nuvens de Júpiter, sua famosa Grande Mancha Vermelha, e a dança diária de seus principais satélites.

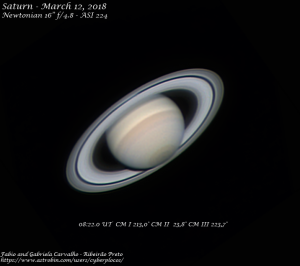

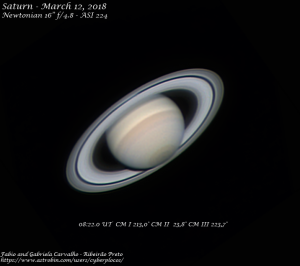

20/7: O Senhor dos Anéis

Vizinho a Júpiter no céu está Saturno, o segundo maior planeta do Sistema Solar, e famoso pelos seu exuberante sistema de anéis. É fácil identificá-lo como o astro mais brilhante ao lado de Júpiter em Sagitário. O planeta atinge a oposição na noite de segunda-feira, 20 de julho.

Até mesmo um pequeno telescópio irá proporcionar uma visão inesquecível dos delicados anéis ao redor do planeta. Instrumentos um pouco maiores poderão revelar detalhes mais sutis como a divisão de Encke, e algumas das maiores luas de Saturno.

22/7: Desafio ao amanhecer

Os povos antigos conheciam os cinco planetas mais brilhantes. Além dos já mencionados Vênus, Júpiter e Saturno, Marte e Mercúrio sempre fizeram parte dos registros dos astrônomos. Desses, Mercúrio é o mais desafiador de ser observado, por estar sempre muito próximo ao Sol.

Mais para o final de julho, Mercúrio se posiciona de maneira favorável para observações, atingindo a maior elongação a leste em 22/7. Pode tentar observá-lo como próximo ao horizonte leste antes do nascer do Sol. Siga a reta formada por Vênus e Aldebaran para encontrar este esquivo astro.

28/7: Chuva em Aquário

Fechando o mês temos a chuva de meteoros Delta Aquarídeos do Sul, provocada por detritos deixados pelo cometa 96P/Machholz. Esta chuva não é muito intensa, mas registra atividade estável espalhada entre julho e agosto, com pico na noite de 28 para 29 de julho.

Seu radiante (ponto no céu de onde os meteoros parecem surgir) situa-se na constelação de Aquário, ao sul da estrela Delta Aquarii. Por isso, é uma chuva mais favorável para os observadores em latitudes ao sul, onde podem atingir taxas horárias de até 10 meteoros por hora em localidades rurais.

Procure a constelação de Aquário na noite de 28 de julho para observar os meteoros Delta Aquarídeos do Sul. Crédito da imagem: T. Bronger.

O melhor horário é a partir das 2h da madrugada. Olhe para o Sul, embora os meteoros possam aparecer em qualquer região do céu. Se possível, procure um local escuro, sem incidência direta de luz. Quanto mais escuro o local, melhor. Uma vez no sítio de observação, permaneça no escuro por pelo menos 30 minutos. Os olhos precisam de pelo menos 10 minutos para se adaptar à escuridão, portanto deixe o telemóvel de lado!

Reserve pelo menos uma hora para observar a chuva. A atividade dos meteoros é inconstante e imprevisível. Podem se passar vários minutos sem nenhum meteoro, e de repente 3 ou 4 aparecem em sequência. Chuvas de meteoros são uma atividade muito mais divertida de ser observada em grupo. Convide os amigos e veja quem consegue observar mais estrelas cadentes!

Na próxima semana …

O Tema do mês continua na semana que vem com os fenômenos astronômicos do mês de agosto, mais constelações típicas do verão, e objetos celestes intrigantes. Até lá e céus limpos!

O Céu de Verão – Parte 2

O Coração da Galáxia

O verão é a estação em que podemos apreciar melhor a região central da nossa galáxia, a Via Láctea. Olhando para o Sul, encontramos as constelações que ornam esta rica zona do céu: Escorpião, Escudo, Ofiúco e Sagitário. É nessa última que estão localizados alguns dos mais encantadores objetos de céu profundo ao alcance de telescópios amadores. Prepare-se para conhecer melhor alguns tesouros escondidos dessa constelação.

Arqueiro ou Bule?

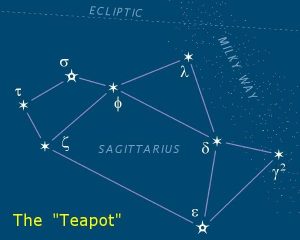

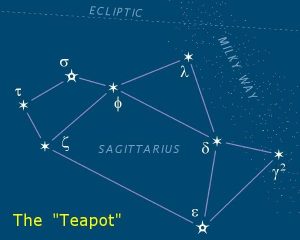

A representação tradicional de Sagitário é de um centauro atirando uma flecha. Assim como acontece com a maioria das constelações, é difícil visualizar essa figura mitológica nas estrelas. Para muitos, é mais fácil enxergar o asterismo conhecido como Bule, que coincide com o corpo e o arco do Centauro.

O primeiro passo é encontrar uma figura em forma de pentágono, que corresponde ao corpo do bule, com a estrela Kaus Borealis (λ Sgr) representando a tampa. Para o lado do Escorpião está o bico do bule, e para o outro lado está sua alça. Completando a analogia, o brilho difuso da Via Láctea parece sair do bico da chaleira, acima da estrela Gamma Sagitarii.

As Coloridas Nebulosas

As nebulosas são gigantescas nuvens de gás encontradas na galáxia. O tipo mais comum de nebulosa são as nebulosas de emissão, associadas a regiões de formação estelar. Essas nuvens colossais abrigam matéria suficiente para formar milhares de estrelas, e brilham graças à radiação ultravioleta liberada pelas suas estrelas mais quentes.

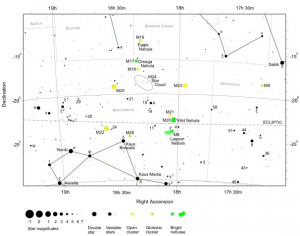

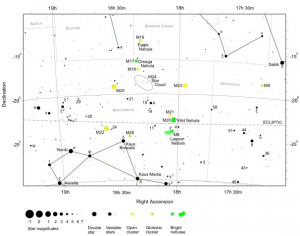

Na direção da constelação de Sagitário encontramos diversas nebulosas proeminentes. A principal é M8, mais conhecida por seu nome popular de Nebulosa da Lagoa.

M8 foi observada pela primeira vez pelo italiano Giovanni Hodierna em 1654, e adicionada ao famoso catálogo de Messier em 1764. É uma das nebulosas mais brilhantes do céu, e pode ser observada até mesmo a olho nu em locais de céu bem escuro.

Distante 5 mil anos luz da Terra, M8 tem cerca de 100 anos luz de extensão. Em seu centro, a primeira geração de estrelas massivas constitui o enxame estelar NGC 6530, cuja luz faz brilhar o gás ao seu redor.

Localizar M8 no céu é uma tarefa fácil com binóculos. Procure a ponta do asterismo em forma de bule que marca a constelação de Sagitário. Aí basta mover seu instrumento na direção norte, até que uma grande mancha acinzentada apareça no campo.

Na mesma constelação encontramos uma outra nebulosa de grande porte, M17, também chamada de Nebulosa Omega, ou Nebulosa da Lagosta. Esta é uma região de formação estelar a 5 mil anos luz da Terra, uma grande nuvem de gás que possui material suficiente para formar quase mil estrelas como o Sol.

Em seu centro, estrelas de alta massa já se formaram, iluminando e excitando o gás ao seu redor e fazendo-o brilhar. O enxame NGC 6618 reúne essas estrelas recém nascidas, todas com no máximo 1 milhão de anos de idade.

M17 guarda muitas semelhanças com outra região de formação estelar bem conhecida, M42, a Nebulosa de Orion. A principal diferença é que vemos M17 de lado, enquanto M42 está virada bem de frente para nós.

Apesar da coloração bastante avermelhada nas fotografias de longa exposição, ao telescópio a nebulosa aparece como uma mancha acinzentada. O olho humano não é sensível o suficiente para perceber cores de um objeto tão fraco.

Mesmo assim é um objeto impressionante. As imagens obtidas com grandes telescópios mostram um nível incrível de detalhe, com faixas de poeira sobrepostas ao fundo brilhante do hidrogênio ionizado.

Para encontrar M17 no céu, comece pela estrela Lambda Sagitarii, e vá em direção à constelação vizinha do Escudo. A nebulosa pode ser identificada graças à sua forma característica parecida com a letra Z.

Completando o trio de nebulosas notáveis de Sagitário temos M20, que se destaca por sua forma circular, atravessada caprichosamente por filamentos escuros de poeira. Essa aparência dividida inspirou seu descobridor Charles Messier a batizá-la pelo nome que a conhecemos até hoje: Nebulosa da Trífida, que significa “dividida em três partes”.

A Trífida é um objeto bastante complexo, reunindo não somente uma nebulosa de emissão, mas também um enxame de estrelas, uma nebulosa de reflexão, e uma nebulosa de absorção. Essas múltiplas classificações demonstram a complexidade do fenômeno de formação estelar.

As estrelas formam-se a partir do gás encontrado nas grandes nuvens moleculares espalhadas no disco da galáxia. Quando a primeira geração de estrelas brilhantes se forma, a nuvem de gás que até então era escura passa a brilhar, iluminada pela radiação ultravioleta emitida pelas estrelas mais quentes, dando origem ao que chamamos uma nebulosa de emissão.

Às vezes, parte da luz estelar é também refletida pelos grãos de poeira espalhados no meio do gás, conferindo uma coloração caracteristicamente azulada. Nessa condição, classificamos a nuvem como uma nebulosa de reflexão.

Quando o meio interestelar tem uma densidade muito elevada de partículas de poeira, nem mesmo a luz das estrelas consegue atravessá-lo. O resultado são regiões escuras sobrepostas a um fundo brilhante, chamadas nebulosas de absorção.

M20 é um objeto especial por apresentar todas essas facetas de uma vez só, e por isso é um daqueles alvos favoritos para observação com binóculos ou telescópios, mas sua grandiosidade se torna mais evidente nas fantásticas fotografias coloridas dessa região.

Enxames jovens e antigos

Sagitário abriga dentro de seus limites muitos enxames estelares jovens, do tipo aberto. Vamos destacar três deles. O primeiro da lista é M18, um enxame bastante jovem, formado há pouco mais de 30 milhões de anos. M18 está bastante próximo da espetacular Nebulosa Omega, dentro da qual encontramos um enxame menor, NGC 6618. Esses dois enxames apresentam idades semelhantes e estão aproximadamente à mesma distância da Terra.

Esse cenário levou alguns astrônomos a propor que M18 e NGC 6618 são um sistema binário de enxames. Exemplos deste tipo de estrutura já foram identificados na nossa galáxia satélite, a Grande Nuvem de Magalhães, mas ainda são escassos na Via Láctea.

Ainda mais jovem é M21, cujas estrelas foram formadas há menos de 5 milhões de anos, um piscar de olhos na escala cósmica. M21 faz parte de uma grande associação conhecida como Sagittarius OB1, que inclui outros enxames e nebulosas. Provavelmente a formação estelar em M21 ainda está em curso, o que significa que num futuro distante ele parecerá ainda mais rico e iluminado do que já é.

Contrastando com a juventude de M21 temos M23. Esse enxame foi formado há quase 300 milhões de anos. Por causa disso, suas estrelas de maior massa já se encontram em estágios mais avançados de sua evolução, ou até mesmo já explodiram como supernovas.

Fotografias de longa exposição da região de M23 mostram uma incrível riqueza de regiões de formação estelar, onde se destacam as já mencionadas nebulosas da Lagoa, Omega e Trífida. Essas imensas nuvens de gás, onde as estrelas estão apenas começando a se formar, irão eventualmente extinguir todo seu gás, dando origem a um enxame evoluído bastante parecido com M23.

Sagitário ainda conta com um grande número de enxames globulares, conjuntos de milhares de estrelas muito antigas formadas junto com a nossa galáxia há milhares de milhões de anos. Os globulares de Sagitário não são tão espetaculares como os famosos Omega Centauri ou M13, em Hércules, mas são alvos interessantes mesmo assim. Em particular, M22 destaca-se como o primeiro enxame globular descoberto, identificado em 1665 pelo alemão Abraham Ihle, e mais tarde adicionado por Messier ao seu famoso catálogo de objetos de céu profundo.

O que ver no céu em agosto

A principal atração de agosto é a famosa chuva de meteoros Perseidas. Esta é talvez a chuva de meteoros mais confiável do calendário, e cuja posição favorece os observadores nas latitudes acima do equador. Temos também boas oportunidades para observar os planetas Júpiter e Saturno logo no início da noite, e Vênus e Marte durante a madrugada.

1/8 Adeus, cometa

O cometa C/2020 F3 (NEOWISE) encantou os observadores durante todo o mês de julho, tornando-se o cometa mais brilhante visível do Hemisfério Norte desde o Hale-Bopp em 1997. A partir da última semana de julho, o cometa se posiciona também de maneira favorável aos observadores do hemisfério Sul, embora com menor brilho.

O Cometa C/2020 F3 encantou os observadores do Hemisfério Norte em Julho. Crédito da imagem: A. Folhas.

No começo de agosto ainda é possível observar o NEOWISE atravessando a constelação da Cabeleira de Berenice, a Oeste, após o entardecer até um pouco depois da meia-noite. Entretanto, o cometa já não apresentará todo o esplendor de julho. Somente com binóculos será possível enxergá-lo.

9/8 Marte encosta na Lua

Durante a madrugada, o planeta vermelho posiciona-se bem ao lado do nosso satélite, numa conjunção muito próxima. Em algumas regiões da América do Sul (Argentina, Brasil, Chile e Uruguai), a Lua chega mesmo a passar em frente a Marte.

Esse fenômeno é chamado ocultação e é espetacular de ser acompanhado pelo telescópio. Se estiver nessa região, confira a este link para consultar o horário da ocultação.

12/8 Chuva de Estrelas

Essa é uma das noites mais aguardadas do calendário pelos entusiastas da astronomia. É quando acontece uma das chuvas de meteoros mais conhecidas: as Perseidas. Esses meteoros são originários da poeira deixada pelo cometa 109P/Swift-Tuttle, que completa uma volta em torno do Sol a cada 133 anos, e que passou próximo à Terra pela última vez em 1992.

Esta é uma chuva de meteoros que favorece os observadores do hemisfério norte. Este ano, o pico da atividade acontece na madrugada do dia 12 de agosto. Em um local de céu escuro, será possível observar dezenas de meteoros por hora. Deve-se olhar para a direção norte. Os meteoros podem ser vistos durante toda a noite, mas o melhor horário é cerca de uma hora antes do amanhecer, quando a constelação de Perseu atinge seu ponto mais alto no céu.+

Como em toda observação de meteoros, procure um local escuro, afastado das luzes das cidades. Deixe seus olhos se acostumarem com a escuridão por pelo menos 15 minutos.

Na próxima semana …

Vamos continuar nosso passeio pelas constelações da região central da galáxia, e ver quais os principais fenômenos celestes do último mês do verão. Até breve e céus limpos!

O Céu de Verão – Parte 3

Continuando nossa série de artigos sobre o céu do verão, chegou a hora de conhecer uma das constelações mais emblemáticas do céu.

Escorpião é uma das poucas constelações que realmente se parece com sua figura mitológica. No seu centro está a estrela Antares, simbolizando o coração do Escorpião.

Acima de Antares encontramos 3 estrelas de brilho semelhante, que simbolizam as garras do Escorpião: Acrab, Dschubba, e Fang.

Na outra direção , as estrelas formam uma figura parecida com a letra J, que marca o corpo e o ferrão do escorpião. Bem na ponta do ferrão estão as estrelas brilhantes Shaula e Lesath.

Antares é uma das estrelas mais brilhantes do céu, e se destaca dentre as milhares de outras estrelas visíveis a olho nu graças a sua cor laranja-avermelhada.

O nome Antares vem do grego, e significa “Rival de Ares”. Ares é como os gregos chamam o planeta Marte, que possui coloração semelhante à de Antares. Essa comparação entre Marte e Antares é milenar. Os astrônomos persas chamavam Antares de Satevis, e a consideravam uma das quatro estrelas reais, junto com Aldebaran, Fomalhaut e Regulus.

O tom rubro de Antares nos dá uma pista de sua temperatura. Antares é considerada uma estrela fria, com temperatura superficial de 3100 graus. Ela é muito brilhante porque tem um diâmetro enorme, quase 900 vezes maior que o Sol.

Se Antares fosse colocada no lugar do nosso Sol, engoliria os quatro planetas mais próximos dele, inclusive a Terra. Sua superfície estaria além da órbita do planeta Marte.

Essas características tornam Antares uma supergigante vermelha, um estágio avançado da evolução estelar. Apesar de ser uma estrela bastante jovem, formada há pouco mais de 10 milhões de anos, terá uma existência bastante breve com final violento.

Com 17 vezes a massa do Sol, o destino final de Antares será explodir em uma supernova, o que deve acontecer daqui algumas centenas de milhares de anos. Quando isso acontecer, seu brilho aumentará tanto que irá rivalizar o da Lua Cheia durante alguns meses.

Escorpião também é famoso pelo grande número de enxames estelares que abriga. Próximo ao ferrão do Escorpião está Messier 7, também conhecido como Enxame de Ptolomeu. É um dos enxames estelares mais brilhantes do céu, facilmente observável a olho nu até mesmo em regiões urbanas.

Messier 7 é conhecido desde a Antiguidade, tendo sido registrado como uma nebulosa pelo astrônomo Claudio Ptolomeu no ano 130 da nossa era. Com a invenção do telescópio, sua natureza estelar foi revelada. Em 1654, o italiano João Batista Hodierna catalogou 30 estrelas no enxame. Um século mais tarde, Charles Messier incluiu o objeto em sua relação de objetos de céu profundo.

Situado a aproximadamente mil anos luz da Terra, Messier 7 foi formado há 200 milhões de anos, e contém centenas de estrelas reunidas em um diâmetro de 150 anos-luz.

Outro enxame proeminente em Escorpião é Messier 6. Não é tão brilhante como o de Ptolomeu, mas mesmo assim pode ser visto a olho nu em locais de céu bem escuro. Possui cerca de 80 estrelas compactadas em um diâmetro de 50 anos luz.

Ao telescópio, as estrelas de Messier 6 lembram lembram vagamente a figura de uma borboleta batendo suas asas, o que lhe rendeu o nome pelo qual o objeto é mais conhecido: Enxame da Borboleta, sugerido pelo astrônomo americano Robert Burnham.

Esta região do céu é extremamente rica em aglomerados estelares, o que a torna especialmente interessante de ser vasculhada usando instrumentos de grande campo, como binóculos ou telescópios “rich field”. Aproveite as noites amenas do verão para explorar a área.

O que ver no céu em setembro

6/9 Marte encosta na Lua (de novo!)

Pelo segundo mês consecutivo, a Lua e Marte fazem uma conjunção próxima, e novamente os sul-americanos serão presenteados com uma ocultação. Quase todo o continente poderá ver o planeta vermelho desaparecer por trás do nosso satélite natural. Se você estiver na região, consulte o horário exato da ocultação no site da International Occultation Timing Association (link).

11/9 Netuno em oposição

Setembro traz a melhor oportunidade para tentar observar o oitavo planeta, descoberto em 1846. Netuno só pode ser observado com telescópios. Instrumentos de pequeno porte mostram um pálido disco azulado, sem maiores detalhes. Procure-o na constelação de Aquário, próximo ao limite com Peixes.

22/9 Adeus, verão

O Sol se despede do hemisfério norte celeste às 14:30 (hora de Lisboa), e só cruzará o equador celeste novamente em 20 de Março de 2021. É o início do outono no hemisfério norte, e da primavera no hemisfério sul.

Na próxima semana …

O último capítulo desse tema do mês trará mais algumas constelações típicas do verão e objetos celestes interessantes. Até breve e céus limpos!

O Céu de Verão – Parte 4

Completando a série de artigos sobre o céu do verão, vamos falar de duas constelações situadas na vizinhança do centro galáctico, próximas aos famosos Escorpião e Sagitário.

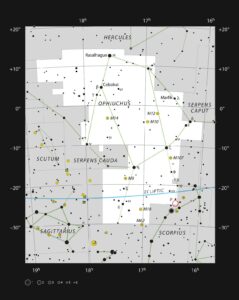

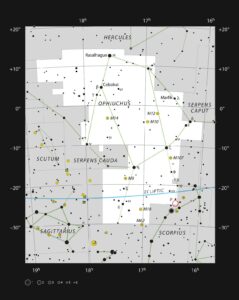

A primeira delas é o Serpentário, também chamada de Ofiúco. Essa constelação começou a aparecer nos catálogos astronômicos por volta do século 4 antes da era cristã. Ela representa Esculápio, o deus da medicina, segurando uma serpente , símbolo da regeneração.

O Serpentário está situado em uma região muito interessante do céu. É atravessado pelo equador celeste, pela eclíptica e pelo plano galáctico. Sua localização no equador celeste implica que ele pode ser observado de boa parte do planeta. Sua estrela mais brilhante é Rasalhague.

O Serpentário é uma das constelações que o Sol cruza durante seu trajeto anual, e é frequentemente visitado pelos planetas. Por causa disso, é considerada a décima terceira constelação do Zodíaco, embora não exista um signo com esse nome.

Nessa constelação encontramos diversos objetos astronômicos interessantes. Graças à sua localização próxima ao plano galáctico, muitos enxames estelares podem ser observados, como Messier 10 e Messier 12.

Mas seu objeto mais conhecido é a região de formação estelar próxima à estrela Rho Ophiuchi, pertinho da fronteira com a constelação do Escorpião. Imagens de longa exposição dessa nebulosa mostram uma variedade incrível de cores.

Vizinha ao Serpentário está a pequena constelação do Escudo. Esta é uma adição relativamente recente aos mapas celestes, proposta pelo astrónomo polonês Johannes Hevelius no século XVII.

Hevelius foi um dos maiores astrónomos do seu tempo, e uma pessoa muito influente na região de Danzig. Em 1679, um incêndio destruiu o observatório construído por Hevelius no teto de sua casa. A família real polonesa ajudou-o a reconstruir o observatório, e foi homenageada com uma constelação no céu.

A atual constelação do Escudo foi batizada por Hevelius como Escudo de Sobieski em homenagem ao Rei João III Sobieski, patrono do astrônomo. Curiosamente, Hevelius não foi o primeiro a nomear uma constelação com nome de monarca.

Seis anos antes, o inglês Edmond Halley já tinha proposto a constelação Carvalho de Carlos, em homenagem ao rei Carlos II da Inglaterra. Mas, ao contrário do Escudo, a ideia de Halley não vingou e logo foi esquecida.

O plano da nossa galáxia atravessa o Escudo, e em consequência disso essa pequena constelação conta com vários objetos de céu profundo, apesar do seu pequeno tamanho.

O mais conhecido deles é o enxame estelar Messier 11, descoberto pelo alemão Gottfried Kirch em 1681 e adicionada pelo francês Charles Messier ao seu famoso catálogo em 1764. É um dos enxames mais ricos do céu, visível com binóculos e que ao telescópio revela centenas de estrelas muito próximas.

Messier 11 foi formado há 220 milhões de anos, e está razoavelmente distante da Terra: 6 mil anos-luz. Suas estrelas mais brilhantes formam uma figura triangular, que lembra uma revoada de aves. Por causa disso, o aglomerado é mais conhecido pelo seu nome popular de Enxame do Pato Selvagem, cunhado pelo inglês William Henry Smith.

No Escudo encontramos também o enxame M26, um grupo de estrelas formado há 90 milhões de anos. M26 pode ser localizado no céu a partir da estrela Delta Scuti, uma gigante amarelada que exibe variações periódicas em seu brilho, provocadas por pulsações. Acompanhando a variação de brilho desse tipo de estrela, é possível determinar a distância de objetos estelares muito distantes, como enxames globulares e até mesmo outras galáxias.

Até a próxima estação!

Chegamos ao fim dessa série de artigos sobre o céu do verão e suas constelações características. Despeço-me desejando ótimas noites de observação do firmamento, e quem sabe nos encontraremos em breve por aqui para conhecermos o céu das demais estações. Até lá e céus limpos!

Summer is Sun’s season, but when night falls, there are plenty of attractions. Mild nighttime temperatures are an invitation to spend the nights looking at the stars.

This year, the season offers two good meteor showers, planets in prime positions for observation, and an elusive lunar eclipse. It also presents an excellent opportunity to explore the area around the galactic center, richly populated with stellar clusters and nebulae.

Welcome to the Theme of the Month! We will meet the main astronomical phenomena of the summer months, the season’s emblematic constellations, and some celestial objects of interest. Get ready for a holiday with the stars!

Author: Gustavo Rojas

Gustavo has a Ph.D. in Astronomy (University of São Paulo, 2008) and began his professional career at the Federal University of São Carlos, Brazil. He has been working for more than 10 years with science outreach and education and acted as the Brazilian representative for ESO Outreach and Science Network from 2011 to 2018. A member of the International Astronomical Union, Brazilian Astronomical Society, and Portuguese Astronomy Society, Gustavo is part of the organizing committee of the Brazilian Astronomy and Astronautics Olympiad, one of the largest science olympiads in the world. Since 2012, Gustavo participates as Team Leader in the International Olympiad on Astronomy and Astrophysics (IOAA) for Brazil (2012-2018) and Portugal (2019). Currently, he works as project coordinator at NUCLIO – Núcleo Interactivo de Astronomia, Portugal.

⬇︎ Click below to read each part of this theme

The Summer Sky – Part 1

In this four-part series of articles, we start with an overview of July’s main celestial phenomena so you can mark it on your calendar. In the following weeks, we will see what will happen during August and September, and also get to know better more typical constellations and its interesting objects.

When is the summer?

In astronomy, the northern summer starts with the June solstice. That’s when the Sun reaches the most northerly position in the celestial sphere. On that date, we have the longest day of the year in the northern hemisphere. However, the highest temperatures are usually recorded a month or two later. In 2020, the solstice takes place on June 20 at 10:43 pm (Portugal time).

Typical constellations

In the northern hemisphere, the summer sky is marked by the well known Summer Triangle, a pattern formed by the bright stars Altair, Deneb, and Vega.

Throughout July, we can see these three stars high in the sky. Looking up around 11 pm, Vega, the brightest one, will be practically at the zenith (the highest point in the sky). Forming the base of the triangle are Altair (second in brightness and the lowest of the trio) and Deneb (the dimmest one, slightly above Altair).

Vega is the chief star in the small constellation of Lyra. Altair is the brightest star of Aquila, the Eagle. Likewise, Deneb is associated with a celestial bird: Cygnus, the Swan. Let’s take a look at some interesting facts about these three constellations.

Lyra, the remarkable little one

As a popular saying goes, good things come in small packages, and at least in Astronomy, this is true indeed. Some of the smallest constellations do hold remarkable treasures.

Lyra, one of the smallest constellations in the sky, symbolizes the lyre of Orpheus, the legendary artist from Ancient Greece known for the enchanting powers of his harmonies. Lyra is one of the constellations present in the Almagest, the most famous ancient astronomical catalog, compiled by Claudius Ptolemy and published in the 2nd century AD.

The Almagest lists the brightness and positions of 1022 stars, distributed in 48 constellations. This set of constellations stood the test time, and most of them are still found in the list of 88 constellations recognized by the International Astronomical Union still in use by astronomers today.

Lyra’s brightest star, Vega, is located at the solar neighborhood, 25 light-years away from Earth. Thanks to its brightness and proximity, it is also one of the best-studied stars in the Universe. Vega was the first star to be photographed and to have its spectra registered. For a long time, it was the reference star in brightness and color astrophysical systems.

Vega is not the only star of astronomical interest in Lyra. The runner-up in brightness, Beta Lyrae, is also a remarkable system. To the naked eye, Beta Lyrae appears to be a star like any other. But in 1784, astronomer John Goodricke discovered periodic variations in the stars’ brightness with a pattern similar to Algol, a star in the northern constellation of Perseus.

Goodricke concluded that, like Algol, Beta Lyrae is a binary stellar system that undergoes a “blackout” every 13 days, when one of the stars passes in front of the other, causing an eclipse.

What Goodricke did not know then is that the stars in the Beta Lyrae system are so close together that their very shapes are distorted by gravity. The closeness between the components also causes matter from one star to be transferred to the other, forming an accretion disk around the pair.

Epsilon Lyrae is another well-known multiple star system, composed of at least five components. An amateur telescope can show the four brightest ones, which earned this system the nickname “The Double Double”.

In Lyra, we also find one of the most beautiful planetary nebulae in the heavens. Messier 57, better known as the Ring Nebula, a favorite target of astronomers. The result of the evolution of a star similar to our Sun, it is a portrait of what our distant future will look like, billions of years from now.

The surprising Eagle

Aquila, the Eagle, is also part of the Almagest’s 48 constellations. The Eagle’s head is marked by its brightest star, Altair, which is also one of the closest stars to Earth, only 17 light-years away. Altair is flanked by two other stars that can be easily seen by the naked eye: Alshain and Tarazed, which form the neck and body of the Eagle.

Early last century, the trio experienced a brightness challenge, albeit for a short time. In June 1918, a previously invisible star in the constellation suddenly increased in brightness, surpassing even Altair to become the second brightest star in the whole sky!

Ancient astronomers called this phenomenon Nova (“new” in Latin; plural: Novae) because they thought it was a new star appearing in the sky. Today, we know that Novae are highly evolved stars, much as their brightest relatives, Supernovae.

Novae take place at binary systems, where one of the components is a white dwarf that captures hydrogen from its companion until a runaway nuclear reaction occurs at the white dwarf’s surface. The brightness of the system increases thousands of times before returning to normal after a few weeks. In some cases, this process can repeat itself several times.

Novae are unpredictable phenomena, and many are discovered by amateur astronomers. Nova Aquilae 1918 was discovered a 17-year-old student, Leslie Peltier, who later became an important researcher of variable stars.

The Swan and its Jewels

The constellation of Cygnus, the Swan, is one of the most well known in the northern hemisphere. Its six brightest stars form the asterism called the Northern Cross. The ancient Greeks imagined that this cross represented a Swan with its wings spread over the Milky Way. The swan would be almighty Zeus in disguise, flying to meet his lover Nemesis. Ptolemy also included the Swan in his Almagest.

The giant star Deneb is the brightest one in Cygnus, representing the birds´ tail. At its beak, we find one of the most interesting stars in the sky, Albireo, which is actually a double system. When viewed through a small telescope, Albireo reveals itself to be a delicate pair formed by a reddish and a blue star, like a heavenly jewel of ruby and sapphire.

Colors are a consequence of stellar temperature. Red stars such as Albireo’s ruby have surface temperatures close to 4200 degrees. Although this is hot enough to melt diamonds, astronomers call these “cool stars”. It’s just a matter of comparison because blue stars such as Albireo’s sapphire can reach 12000 degrees and even more. This is more than twice the surface temperature of our Sun.

At the telescope, the pair looks very close, but in reality, the components of Albireo are very far apart. It is believed that one star takes 100,000 years to complete one lap around the other.

On the Swan’s neck, we find an enigmatic object invisible to conventional telescopes. Cygnus X-1 was only discovered in 1964 by a pioneering X-ray astrophysics experiment loaded on board of a rocket. Cygnus X-1 is a binary system, composed of a supergiant blue star and an invisible compact object weighing 15 solar masses. The blue star’s outer gas layers are captured by the invisible object gargantuan gravitational field, accumulating in a disk around it. The gas in this disk is heated to millions of degrees, emitting large amounts of X-rays.

Although it is not possible to directly observe the mysterious object, calculations leave no doubt that several solar masses confined in such a small volume can only be found in the most extreme object in the Universe: a black hole, a region of space where the gravitational field is so intense that not even light can escape from it.

The existence of black holes has always been a controversial topic in Astrophysics. The Cygnus X-1 black hole is famous because of a wager involving renowned scientists Stephen Hawking and Kip Thorne.

In 1975, Hawking made a bet with Thorne that Cygnus X-1 would not harbor a black hole. If he won, he would win a one-year subscription to the Private Eye humor magazine, but if he lost, Thorne would receive from Hawking one year of Penthouse issues.

As research on Cygnus X-1 nature advanced, Hawking finally acknowledged in 1998 that he had lost the bet. This in fact did not disappoint him, since most of Hawking’s own work is about black holes nonetheless.

Cygnus contains some notable stellar clusters. The most notorious is M29, which is very close to the star Gamma Cygni, located right in the center of the Northern Cross.

At 6,000 light-years from Earth, M29 contains at least 50 members. The brightest are young, bluish stars of spectral class B0. It is estimated that this stellar group was formed about 10 million years ago, making it one of the youngest star clusters known.

When viewed through the telescope, the brightest stars in M29 form a curious figure with a quadrilateral at the base, earing the cluster the curious nickname of Cooling Tower, a reference to the structure found in some industries and nuclear plants.

What to see in the sky in July

7/4: The Sun farther away

Our annual journey around the Sun does not follow a circular path. The Earth’s orbit is slightly oval, and, as a result, the Earth-Sun distance varies slightly throughout the year. The maximum approach, or perihelion, takes place in January and measures approximately 147.1. million km. In July, it’s time for us to be a few million km further away from our star. This point in orbit is known as aphelion with a distance to the sun of nearly 152.1 million km.

4 million km is an absurd distance for humans (more than 10 times the distance to the Moon), but even this amount does not result in a noticeable change in the Sun’s apparent size, which only shows up photographs.

7/5: Moon in the shade

There is a penumbral lunar eclipse during Sunday’s early hours. In this type of eclipse, the Moon crosses the umbra, the not-so-dark region of the shadow that Earth casts in space. Penumbral eclipses are always subtle, and hardly discernible to the naked eye. The phenomenon becomes more evident in photographs or when observed through optical instruments.

From Portugal, it will be possible to follow most of the eclipse, which starts at 04:07 and reaches its peak at 5:29.

7/8: The Morning Star

For planetary observers, July will be a full course banquet. Beginning the month is a good opportunity to enjoy our closest neighbour reaching top brightness. Venus, currently appearing as a morning star, is just above reddish Aldebaran, the brightest star in constellation Taurus, the Bull.

7/14: Jupiter’s night

This month highlights the largest planets in our Solar System, Jupiter and Saturn. Jupiter reaches opposition on the 14th. In astronomy, opposition is the configuration in which the Earth positions itself exactly between the Sun and a superior planet (that is, a planet which is farther away to the Sun than we are). On this occasion, the planet appears higher in the sky, and also can be observed for a longer time. Nights around opposition are therefore the best time for observing the planets.

This year, Jupiter can be observed in the direction of the constellation Sagittarius, shining more than any other star in the area. If you have a telescope, do not miss the opportunity to marvel at Jupiter’s intricate cloud structure, the famous Great Red Spot, and the daily dance of its largest satellites.

7/20: The Lord of the Rings

Side by side to Jupiter in the sky is Saturn, the second-largest planet in the Solar System, famous for its exuberant ring system. It is easy to identify it as the brightest star next to Jupiter in Sagittarius. The ringworld hits opposition on the night of Monday, July 20.

Even a small telescope will provide an unforgettable view of the delicate rings around the planet. Slightly larger instruments may reveal more subtle details like Encke’s division between the rings, and some of Saturn’s largest moons.

7/22: Dawn Challenge

The five brightest planets are known since the dawn of mankind. In addition to the aforementioned Venus, Jupiter, and Saturn, Mars and Mercury have always been part of astronomers’ records. Among these five classical planets, Mercury is the most challenging to observe, as it is always very close to the Sun and frequently lost in its glare.

Towards the end of July, Mercury will be in a favorable position for observations, reaching the greatest eastern elongation on the 22nd. You can try to observe it close to the eastern horizon before sunrise. Follow the line formed by Venus and Aldebaran to find this elusive target.

7/28: Shower in Aquarius

Closing the month is the Southern Delta Aquarids meteor shower, caused by debris left by comet 96P/Machholz. This shower is not very intense but registers stable activity spread between July and August, peaking in the night from 28th to 29th.

The shower’s radiant (point in the sky from which meteors appear to emanate) is located in the constellation Aquarius, just south of the star Delta Aquarii. For this reason, this shower is more suited to observers in southern latitudes, where it can reach hourly rates of up to 10 meteors per hour in rural locations.

The best time to observe is from 2 am onwards. Look South, but keep in mind that the meteors can appear anywhere in the sky. If possible, go to a dark site away from artificial lights. The darker the place, the better. Once at the observation site, stay in the dark for at least 30 minutes. The eyes need at least 10 minutes to adapt to the darkness, so put your mobile phone away!

Allow at least an hour to observe the shower. Meteor activity is fickle and unpredictable. Several minutes can pass without a meteor, and suddenly 3 or 4 appear in sequence. Meteor showers are much more fun to observe in a group. Invite a few friends to spot the shooting stars!

Next week …

Theme of the Month continues next week with a list of astronomical phenomena in August, more typical summer constellations, and intriguing celestial objects. Until next week and clear skies!

The Summer Sky – Part 2

The Heart of the Galaxy

Summer is prime time to appreciate the central regions of our galaxy, the Milky Way. Looking South, we find the constellations that ornate this rich area of the sky: Scorpius (the Scorpion), Scutum (the Shield), Ophiuchus (the Serpent Holder) and Sagittarius (the Archer). It is in the latter that some of the most enchanting deep sky objects within reach of amateur telescopes are located. Let’s get to know better some hidden treasures of this constellation.

Archer or Teapot?

Sagittarius represents a centaur shooting an arrow. As with most constellations, it is difficult to visualize this mythological figure in the stars. For many, it is easier to see the asterism known as the Teapot, which coincides with the Centaur’s body and bow.

To find the Teapot, start by the pentagon-like shape. This is the teapot’s body, with star Kaus Australis representing the lid. To Scorpius’ side is the teapot’s spout, and to the other side is the handle. If you want to push a little further, imagine that the diffuse Milky Way glow is steam escaping the spout, just above the star Gamma Sagittarii!

The Colorful Nebulae

Nebulae are gigantic clouds of gas found in the galaxy. The most common are emission nebulae, associated with star-forming regions. These colossal clouds harbor enough matter to form thousands of stars and shine thanks to the ultraviolet radiation released by their hottest stars.

In the direction of Sagittarius, we find several prominent nebulae. The chief one is M8, better known by its popular name Lagoon Nebula.

M8 was first observed by Italian Giovanni Hodierna in 1654 and later added to the famous Messier catalog in 1764. It is one of the brightest nebulae in the sky and can be seen even with the naked eye in dark sky locations.

At 5,000 light-years away from Earth, M8 is about 100 light-years across. At its center, the first generation of massive stars constitutes star cluster NGC 6530. The powerful ultraviolet light emitted by these stars excite the gas in M8 and make it shine.

Locating M8 in the sky is an easy task with binoculars. Aim for the teapot’s tip, then move your instrument northwards, until a large grayish spot appears in the field.

Near the Sagittarius-Scutum border we find another large nebula, M17, also called Omega Nebula or Lobster Nebula. Also a star-forming region 5,000 light-years from Earth, this gas cloud has enough material to form thousands of stars like the Sun. In its center, the very young NGC 6618 shines with its massive stars, just 1 million years old.

M17 bears many similarities to another well-known stellar nursery, the Orion Nebula (M42). The main difference is that we see M17 from the side, while M42 is positioned face-on.

Despite the reddish color shown in long exposure photographs, at the telescope, the nebula appears as a grayish spot. The human eye is just not sensitive enough to perceive the colors of such a dim object.

Nonetheless, it is an impressive object. Images obtained with large telescopes show an incredible level of detail, with streaks of dust overlaid on the bright background of ionized hydrogen light.

To find M17 in the sky, start at star Lambda Sagitarii, then head towards the neighboring constellation of Scutum (The Shield). The nebula can be identified thanks to its characteristic shape similar to the letter Z.

Completing the trio of Sagittarius’ prominent nebulae is M20, which stands out for its circular shape, capriciously crossed by dark filaments of dust. This fragmented appearance led its discoverer, Charles Messier, to name it as Triffid Nebula, which means “divided into three parts”.

The Triffid is a very complex object, harboring not only an emission nebula, but also a star cluster, a reflection nebula, and an absorption nebula. These multiple classifications demonstrate the complexity of star formation.

Stars are born within large molecular clouds scattered across the galaxy’s disk. When the first generation of bright stars forms, the gas in the cloud, which up to this point was dark, becomes illuminated by the ultraviolet radiation emitted by hot stars and shines, giving rise to an emission nebula.

Sometimes, part of the starlight is also reflected by grains of dust among the gas, giving it a characteristic bluish color. When this happens, we call the cloud a reflection nebula.

Sometimes the interstellar medium has a very high density of dust particles, so high that not even starlight can penetrate it. This results in dark regions overlapping a bright background, forming an absorption nebula.

M20 is a special object because it presents all these aspects at once. This reason alone makes it one of the favorite targets for observation with binoculars or telescopes, but the true grandeur becomes more evident in the fantastic long-exposure color photographs taken with telescopes.

Clusters, young and old

Sagittarius is home to many young, open star clusters. We will highlight four of the most famous. The first on the list is M18, a very young cluster, formed just over 30 million years ago. M18 is very close to the spectacular Omega Nebula, within which we find a smaller cluster, NGC 6618. These two clusters are similar in age, and approximately at the same distance from Earth.

This scenario led some astronomers to propose that M18 and NGC 6618 form a binary cluster system. Examples of this type of structure have already been identified in our satellite galaxy, the Large Magellanic Cloud, but are still scarce in the Milky Way.

Another remarkable cluster is M21, which stands out for being one of the youngest star clusters ever identified. Its stars were formed less than 5 million years ago, a blink of an eye on the cosmic scale. M21 is part of a much larger stellar association known as Sagittarius OB1, which includes other clusters and nebulae. Probably the star formation process in M21 is still ongoing, which means that in a distant future, it will look even richer and brighter than today.

Contrasting to M21’s youth is M23, a cluster formed almost 300 million years ago. The relatively old age has caused most of its massive stars to leave the main sequence and reach more advanced evolutionary stages. Some of its members may have already disappeared, exploding as supernovae.

Long exposure photographs of the M23 region show an incredible wealth of star-forming regions around it, including the aforementioned Lagoon, Omega, and Trifid nebulae. In these immense gas clouds, the star-forming process is just starting. Eventually, much of the gas currently in these nebulae will be converted into stars, giving rise to evolved clusters not much different from M23.

Sagittarius also hosts a large number of globular clusters, an old collection of stars many billion years in age. They are not as spectacular to the eye as other famous globular clusters elsewhere in the sky such as Omega Centauri or M13 but are interesting nonetheless. Perhaps the most well known is M22, which was the first-ever globular cluster identified as such. This happened in 1665 when german-born Abraham Ihle observed it. A century later, Frenchman Charles Messier realized that the object was composed of individual stars, and added the cluster to his famous catalog of deep-sky objects.

What to see in the sky in August

August’s main event is the famous Perseid meteor shower. This is perhaps the most reliable meteor shower on the calendar, and its position favors observers at latitudes above the equator. It’s also a good month to observe the planets Jupiter and Saturn early in the evening, and Venus and Mars at dawn.

8/1 Goodbye, comet

Comet C/2020 F3 (NEOWISE) dazzled skywatchers throughout July, becoming the brightest comet visible in the Northern Hemisphere since Hale-Bopp in 1997. Late in July, the comet also became visible for observers in the southern hemisphere.

Early in August, it will be still possible to observe the comet in the constellation of Coma Berenices. Look west after dusk until midnight. Don’t expect the same show put up in July though, as the comet has lost much of its brightness and has become a binocular object.

8/9 Mars grazes the Moon

After midnight, the red planet positions itself right next to our natural satellite, in close conjunction. Observers in some regions of South America (Argentina, southern Brazil, Chile, and Uruguay) will observe the Moon passing exactly in front of Mars.

This phenomenon is called an occultation and is spectacular when witnessed through a telescope. If you are in the occultation area, do not miss it. Check the link below for more information on the exact time of the phenomenon

http://www.lunar-occultations.com/iota/planets/0809mars.htm

8/12 Stars Rain Down

This is one of the most anticipated dates on the calendar for astronomy enthusiasts, when one of the best-known meteor showers occurs: the Perseids. These meteors originate from the dust left by Comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle, which completes an orbit around the Sun every 133 years. The last time it visited the inner solar system was in 1992.

This meteor shower favors observers in the northern hemisphere. This year, the peak of activity takes place at dawn on the 12th of August. In a dark sky, it is possible to see dozens of meteors per hour. You should look towards the north. Meteors can be seen all night long, but the best time is about an hour before dawn when constellation Perseus reaches its highest point in the sky.

As with any meteor observation, look for a dark place, away from city lights. Let your eyes get used to the darkness for at least 15 minutes, and enjoy the show!

Next week …

We will continue our tour of the constellations of the central region of the galaxy, and check the main celestial phenomena of the last month of the summer. See you soon and clear skies!

The Summer Sky – Part 3

Continuing our series of articles on the summer sky, it’s time to meet one of the most emblematic constellations in the sky.

Scorpio is one of the few constellations that actually resemble its mythological figure. It is led by the reddish star Antares, the heart of the scorpion. Near Antares, we find 3 stars of similar brightness, which symbolize the claws of the animal: Acrab, Dschubba, and Fang. In the other direction, we find a star pattern similar to the letter J, which marks the body and the stinger of the scorpion. Right at the tip of the stinger are bright stars Shaula and Lesath.

Antares is one of the brightest stars in the sky and stands out from the thousands of other stars visible to the naked eye thanks to its reddish-orange color. Its name comes from the Greek, and means “rival to Ares”. Ares is Mars’ name in Greek. The comparison arises from the color of both celestial objects and is much older than the Greek civilization. Ancient Persian astronomers called it Satevis, and considered it one of the four royal stars, along with Aldebaran, Fomalhaut, and Regulus.

The red hue of Antares gives us a hint of its temperature. With a surface temperature of 3100 degrees, Antares is considered a cool star by astronomers. It is very bright thanks to its huge diameter, almost 900 times larger than the Sun’s. If we replaced our Sun with Antares, it would swallow the four inner planets, including Earth. Its surface would stretch beyond Mars’ orbit.

These characteristics make Antares a red supergiant, an advanced stage of stellar evolution. Despite being a relatively young star, just over 10 million years old, Antares will have a very short existence and a certain violent ending.

With 17 times the mass of the Sun, Antares’ fate is to explode as a supernova, which should happen in a few hundred thousand years. After the explosion, its brightness will increase so dramatically that it will rival that the Full Moon for months.

Scorpio is also famous for its large number of star clusters Next to the stinger is Messier 7, also known as Ptolemy Cluster. It is one of the brightest star clusters in the sky, easily observable with the naked eye even in urban regions.

Known since ancient times, Messier 7 was registered as a nebula by astronomer Claudius Ptolemy in the year 130. With the invention of the telescope, its stellar nature was revealed. In 1654, the Italian Giovanni Battista Hodierna cataloged 30 stars in the cluster.

A century later, Charles Messier included the object in his list of deep-sky objects. Roughly at one thousand light-years from Earth, Messier 7 was formed 200 million years ago and contains hundreds of stars gathered in a diameter of 150 light-years.

Another prominent cluster in Scorpio is Messier 6. Although not as bright as Ptolemy’s, it is still within naked eye reach in dark skies. There are around 80 compacted stars in a diameter of 50 light-years.

At the telescope eyepiece, the stars of Messier 6 resemble vaguely the figure of a butterfly flapping its wings, which earned it the name by which the object is best known: Butterfly Cluster, suggested by American astronomer Robert Burnham.

This region of the sky is extremely rich in star clusters, which makes it especially interesting to observe with wide-field instruments, such as binoculars or “rich field” telescopes. Take advantage of the mild summer nights to explore the area.

What to see in the sky in September

9/6 Mars behind the Moon (again!)

For the second consecutive month, the Moon and Mars make a close conjunction, and again South Americans will be gifted with an occultation. Almost the entire continent will be able to see the red planet disappear behind our natural satellite. If you are in the region, check the exact occultation time on the International Occultation Timing Association website, here.

9/11 Neptune in opposition

September brings the best opportunity to try to observe the eighth planet, discovered in 1846. Neptune can only be observed with telescopes. Small instruments show a pale blue disc, with no further details. Look for it in the constellation Aquarius, near the border with Pisces.

9/22 Goodbye, summer!

The Sun says goodbye to the northern celestial hemisphere at 2:30 pm (Lisbon time), and will not cross the celestial equator again until March 20, 2021. It is the beginning of autumn in the northern hemisphere, and spring in the southern hemisphere

Next week …

The final chapter of the Theme of the Month will bring more interesting constellations and celestial objects. See you soon and clear skies!

The Summer Sky – Part 4

Completing this series of articles about the summer sky, let’s meet two constellations in the vicinity of the galactic center, near Scorpio and Sagittarius.

The first one is Ophiuchus, the Serpent Bearer. This constellation appears in astronomical catalogs as old as 4th century BC. It represents Aesculapius, the god of medicine, holding a serpent, a symbol of regeneration.

Ophiucus is located in a very interesting region of the sky. It is crossed by the celestial equator, the ecliptic, and the galactic plane. Its location on the celestial equator implies that it can be observed from much of the planet. Its brightest star is Rasalhague.

Ophiucus is one of the constellations crossed by the Sun during its annual journey and is frequently visited by the planets. It is considered the thirteenth constellation of the Zodiac, although there is no sign with that name.

In this constellation, we find several interesting astronomical objects. Thanks to its location close to the galactic plane, many star clusters can be observed, such as Messier 10 and Messier 12.

The best-known deep sky object in the area is the star formation region near the star Rho Ophiuchi, close to the border with Scorpio. Long exposure images of this nebula show an incredible variety of colors.

Next to Ophiucus is the small constellation of the Scutum, the Shield. This is a relatively recent addition to celestial charts, proposed by Polish astronomer Johannes Hevelius in the 17th century.

Hevelius was one of the greatest astronomers of his time and was a very influential person in the Danzig region. In 1679, a fire destroyed the observatory built by Hevelius on the roof of his home. The Polish royal family helped him rebuild the observatory, and in return, was honored with a constellation.

Scutum was named by Hevelius as Scutum Sobiescianum (Sobieski Shield), in honor of King John III Sobieski, the astronomer’s patron. Interestingly, Hevelius was not the first astronomer to name a constellation after a monarch.

Six years earlier, Englishman Edmond Halley had already proposed a constellation named Robur Carolinum (Charles’ Oak), in honor of King Charles II of England. But, unlike Scutum, Halley’s proposal didn’t fare well and was soon forgotten.

The plane of our galaxy crosses Scutum, and as a result, this small constellation has several deep-sky objects, despite its small size.

The best known is star cluster Messier 11, discovered by Gottfried Kirch in 1681, and added by Charles Messier to his famous catalog in 1764. It is one of the richest clusters in the sky, visible with binoculars, revealing hundreds of very tightly packed stars.

Messier 11 was formed 220 million years ago and is reasonably far away from Earth: 6,000 light-years. Its brightest stars form a triangular figure, which brings to mind a flock of birds. This gave rise to its popular name Wild Duck Cluster, coined by Englishman William Henry Smith.

In Scutum, we also find the cluster Messier 26, formed 90 million years ago. M26 can be located in the sky from star Delta Scuti, a yellowish giant with periodic brightness variations caused by pulsations. Astronomers use this type of star to determine the distance of very distant stellar objects, such as globular clusters and others, even other galaxies.

Until next season!

We have come to the end of this series of articles on the summer sky and its typical constellations. I say goodbye and wish you an excellent observing season. We will meet soon again to explore the skies of the other seasons. Take care and clear skies!

Leave a Reply